What I Talk About When I Talk About Investing

Malt Liquidity 107

Investing, like many general terms, has a lot of context-dependent definitions that all revolve around the same concept of “allocate resources to something now and reap the increased benefits later.” The most commonly invested resource is time, of course — bit by bit the time we allocate to essential skills builds into specialized skills and results in being able to utilize the fruits of those investments in a career to acquire a salary. Investing in anything revolves around the understanding that the net future value of some assets’ growth is worth more than the net present value of those resources.

One of the most common questions I’m asked is “what stocks should I buy?”, and I consistently find it one of the hardest questions to answer, because I come from a trading background rather than an investment research one and philosophically disagree with the entire idea of stock-picking on the thesis of company outperformance. Investing in a financial context is traditionally defined as capital apportioned across assets for the sake of generating income or capturing price appreciation (or both.) While this could take a “what stocks should I buy” form from a layman’s view, what’s actually presented is a min-max optimization problem: given a certain timeline, how do I maximize exposure to a desired market while minimizing downside risk?

(Note: the importance of a defined timeline is simply due to the fact that the infinite growth assumption a) destroys your ability to reasonably take a profit and b) ignores that “on a long enough timeline, every survival rate drops to zero.)

This leads us to seemingly simple yet powerful intuitions such as the age-scaled stock/bond split, which embodies the philosophy that the older you get, the less exponential upside/downside risk you need at the cost of guaranteed income (because a bond held to duration is fixed income, of course, as the market fluctuation is immaterial in that scenario. This is the logic behind the BTFP program.) Note that all downside risk is not created equal; for example, VC investments have a ludicrously low hitrate, where most companies go to zero yet a few go gangbusters and pay for the rest, because nobody has their entire portfolio allocated to such a strategy. Concepts like the Kelly criterion allow us to understand that it’s OK to bet on a longshot as long as we don’t overallocate. The financial world is so large, however, that these concepts quickly snowball into an incomprehensible barrage of jargon — what follows is an attempt to simplify it.

The Rambling Trader

As made evidently clear by my writing, I don’t believe in fundamental value

A fundamental principle of any Buffett-and-Graham-ite is that “the dollar matters”. Every thicket of valuation, business strategy, and investment strategy is built off of optimizing “the value of the dollar”.

But what happens when the dollar doesn’t matter?

due to the rewiring of investor mentality that ZIRP led to, which made the wealth-creation mechanism the source of wealth itself (as I’m wont to say.) Remember, if you’re under the age of ~45, you haven’t seen “real” rates while in a senior role until now. While big funds still allocate on a value basis,

The vast majority of money that moves in and around the market is based on the philosophy that whatever is invested in will create future cash flow rewarding current shareholders, who hold a right to their share of the output... Note that these investors generally operate with a philosophy that they don’t want to react to day-to-day market movements. They are in it for the cash flow created over time and the movement in share price that will reflect that. So we want to focus on what will motivate them to decide that they want to demand liquidity and increase or downsize their positions.

Investing is driven by valuation — taking snapshots of a company’s performance over time and stringing them together to estimate future outlook. The question valuation asks is very simple: given an investment in a company, what do I own now, what am I expected to own in the future, and how much is it worth at present value?

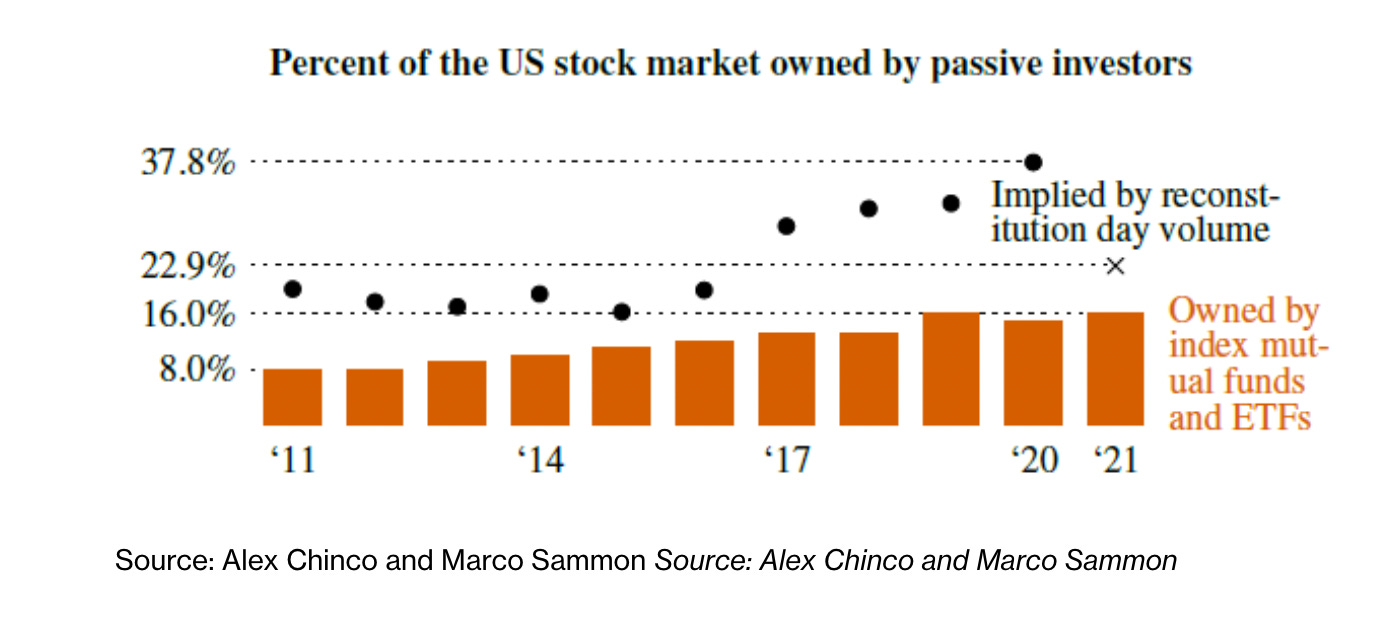

more and more of the market is shifting towards passive investment:

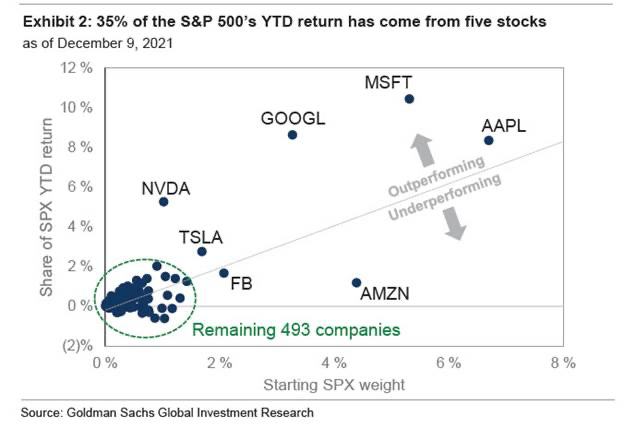

What this means is that the market cannot move without its biggest stocks coming along for the ride. In fact, that’s what drives the returns, as we saw in 2021:

As I noted then,

a sort of push-and-pull effect occurs: “real” flow goes into large caps, they rebalance as part of the ETFs they are in, “passive” flow goes into ETFs and drags the rest of the stocks up along with the large ones to a smaller extent.

But remember the optimization problem from earlier — AAPL and MSFT, the two largest and most reliable stocks in any index, have betas of roughly .9-1.25 (indicating the volatility of these stocks relative to the index — .9 would be MSFT is 90% as volatile as the index in the same direction for example.) while TSLA has a historical beta of over 2. If the index is going to move with these two stocks, it doesn’t entirely make sense to replicate this exposure through individual stocks without “compensation” for the extra volatility taken.

Thus we arrive at my philosophy: to “solve” the optimization problem (“given a certain timeline, how do I maximize exposure to a desired market while minimizing downside risk”) I posit two things: first, that “snapshot-driven value investing” does not move the market in day-to-day real time (but rather quarterly), and second, that any sector cannot move without its heaviest weightings following suit. So if I wanted exposure to financials, I’d look up XLF and note that without BRK or JPM, this sector is going nowhere.

While this has recently been noticed with regards to NQ and its overweighting to six companies (which led tothe process of rebalancing it), this doesn’t remove the cross-market correlated trading patterns that developed due to the fact that liquidity across ETF components is equal opportunity, not equal outcome, and that the market is “made” as a whole rather than each individual ticker having a specialized book — Stock #372 in SPY simply will see nowhere near the volume of AAPL, as congregated drift is a function of true volume in the market rather than the gravity of the heaviest components.

With these assumptions, a target timeline, and an understanding of what market exposure one desires, it’s almost trivial to construct a portfolio. The method I use to determine my “portfolio timeline” is by simply following the Fed. Falling rates lift all ships while rising rates dampen debt-fueled speculation, resulting in a concentration in “reliable” stocks regardless of whether or not they’re fiscally in ship-shape. Accordingly, I had a certain shape of portfolio during ZIRP which molded to the telegraphed rising rate environment once hikes commenced. However, I didn’t want my exposure to be entirely that of the market, otherwise I’d simply be at the whim of the rallies and valleys of the S&P500. Note that diversifying your holdings mathematically dampens volatility, but it’s kind of meaningless if your holdings are correlated. Thus, to diversify my portfolio, I look for varying types of exposure; something like XOM, the heaviest component of the XLE sector ETF,

is theoretically less correlated with the broader market due to the fact that it moves on commodity pricing rather than a direct function of monetary policy. Of course, macroeconomic turbulence is shared across sectors, which might induce some similar price movement, but over time the snapshots that the largest investors allocate by differ such that the price action is sufficiently divergent to treat commodities as appropriate portfolio diversity.

Beta neutral exposure is more interesting in that some individual stocks have characteristics that make them uniquely resistant to “normal” market fluctuations. One of my historical favorites is VIRT, the only publicly traded market maker (for now.) The cute thing about VIRT is that its business model necessarily makes it approximately delta neutral, with their fortunes shifting on overall market volatility and how much they can capture relative to their competitors. While there were standard single-company risks involving regulation and competition (such as proposed PFOF regulation and the fact that Citadel started crushing them over time), the yield and the overall market conditions when retail trading proliferated made it a fantastic counterbalance to a straight market long. One notes that its historical beta is a shockingly low .24, some of the lowest you can find without delving into small caps or negative beta-designed instruments.

Putting these stocks together, we get a remarkably simple yet efficient 4-stock portfolio. Since we want to have primarily overall market exposure, we can split that portion of our portfolio evenly between MSFT and AAPL (to average betas), allocating ~70% of our capital to those two. For uncorrelated commodities exposure, we allocate a further 20% to XOM. Lastly, for mostly beta neutral exposure, we’ll allocate the rest to VIRT. Note that this is as rudimentary as it gets — it’s probably better to hold a few more companies across other sectors, such as consumer staples or financials, and also not be tied to one company’s fortunes relative to the sector. But check out this simple portfolio’s performance since VIRT’s IPO!

Note that this portfolio is stagnant over time and that the market rocketed up for a majority of this timespan — but that’s why the Sharpe, max drawdown, and market correlation stats are so valuable. Here’s SPY over the same period:

The insight of this style of portfolio construction is that I disregard the idea that there is some novel insight to be gained in researching individual companies or that allocating capital to public markets is supposed to hockey-stick my net worth quickly. There are better venues for those goals, including novel trading ideas (immutable edge), starting a business, or private investments (with the requisite net worth and proper Kelly behavior.) I also disregard the idea that beating the market is a worthwhile goal — as I’ve noted about the S&P 500 before

there’s this misconception that passive funds are truly passive — take the S&P 500, for example, the most allocated-to “passive investment” and benchmark…

While colloquially we think of the S&P 500 as the “largest 500 stocks”, this isn’t exactly the case — otherwise you would see a constant updating of the holdings based on size. Instead, there are criteria that a committee uses to deem which stocks are in the index…

Which, of course, leads us to the profitability filtering, which rids us of this conundrum — in effect, the S&P 500 is essentially biased towards the best-performing companies. No wonder so many actively managed funds fail to beat this! They’re benchmarked against constantly moving goalposts.

Instead, I think striking a balance between generating an (ideally inflation-beating) return versus avoiding the full drawdowns of the overall market is a much more worthy goal. Of course, based on your risk tolerance/overall time horizon, you can prioritize the return versus the drawdown avoidance accordingly.

I’m sure I’ll return to this topic in the future, but I’ll end this with a summary of my mindset:

There is no reason to acknowledge the market as some sort of supreme being that knows better than everyone else, because there is information asymmetry and value to be added in localized areas of investment. The futility of betting against the market comes from ignoring that it’s structured such that the collective size gets what it wants, through coordinated allocation and/or the assistance of monetary policy. As such, valuation is not a short thesis and attempting to impose your own beliefs on the markets without any catalysts on the horizon is a recipe for disaster. One does not need to believe there’s any purpose to investing to profit from it — the true postmodern market philosophy.