Part 1: You and I, We’re Not So Different

For public companies, there has always been an undercurrent of criticism with regards to the supposed “short-termism” that the cycle of quarterly earnings reports brings. On its face, this is not exactly wrong — the median tenure for an S&P 500 CEO has decreased from 6 years to 4.8, while Ford has promptly fired its past two CEOs after three years due to an inability to turn the flailing automaker’s stock around. Passive investing somehow makes this even more complicated — you don’t really know which shareholders you’re answering to,

If I own an airline sector ETF, I don’t want outsized performance by one airline at the expense of others. Instead, I’d prefer to have the pie gradually increase and be meted out to each airline according to their need. Certainly, this is confusing for the management of each company, as a traditional fiduciary responsibility implies that one works for the sake of their shareholders. But should the shareholders that solely hold United be catered to at the expense of the larger institutional holders (such as Vanguard) who hold United, American, and Delta, and would actually suffer losses if United starkly outperformed the rest?

and being removed from a gargantuan ETF is a death sentence for liquidity. The theory goes that this incentivizes new CEOs to do whatever they can to prop up the share price lest they be replaced. Perhaps we simply need to give them a bit more time.

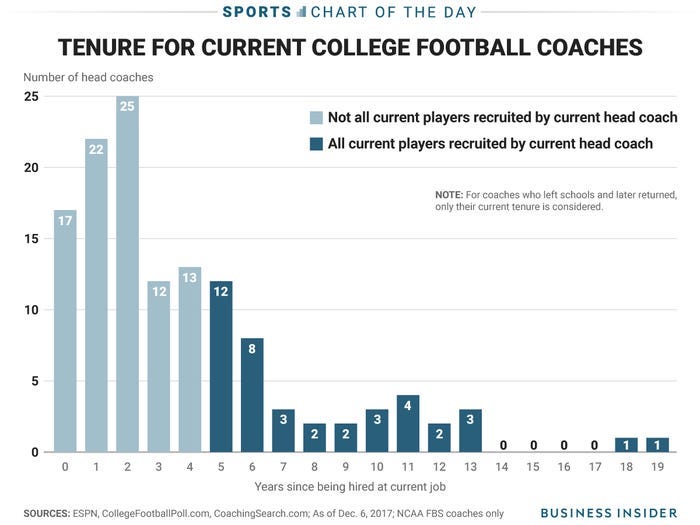

The lifespan of a college football coach is quite similar. You have an incredibly short time horizon to create a legacy, or you’d better grab your jacket and start packing up your office, with the tenure of an average coach clocking in at around 3.8 years.

Beyond Nick Saban, Dabo Swinney, or, I guess, Kirk Ferentz, the college system largely only recognizes rapid success and rapid replacement. Since Mack Brown left Texas, they’ve seemingly followed the hiring and firing pattern of Ford — Charlie Strong lasted about 3 years from 2014 to 2016, and Herman lasted the next 3 from 2017 to 2020, mirroring Ford’s James Hackett (who, funnily enough, was responsible for bringing Harbaugh to Michigan.) Alas, Texas might finally be back under Sarkisian? Hopefully? While the corporate short-termism argument is complex and the evidence isn’t particularly damning, the college football apparatus’s obsession with short-termism is flat out killing the sport — and yet, the money keeps increasing,

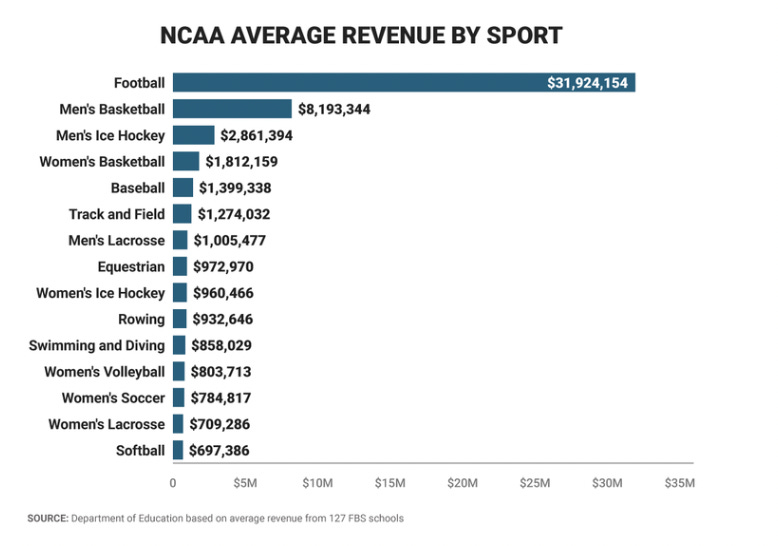

Total revenues [for college sports] have more than tripled since 2003… Out of the 2078 institutions that have athletic programs, those 65 [power college ~ed.] schools generated 54% of all college sports revenue. Essentially, 3 percent of all college programs bring in more than half of all money, and they do that primarily by plowing money into their massive football programs.

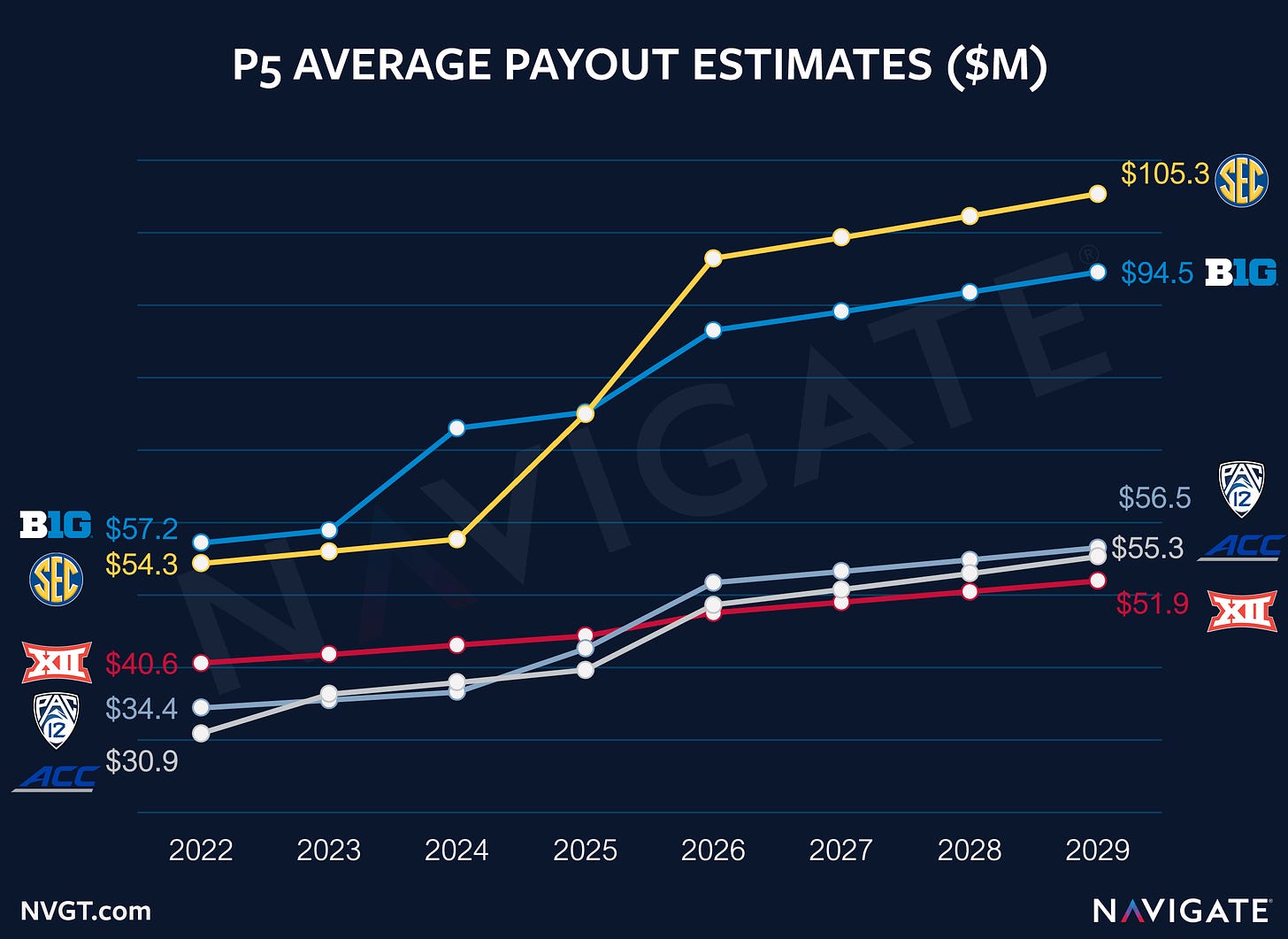

with the P5 conferences projecting even greater and greater forward revenues and distributions. But is this really sustainable? More importantly, is this even “college football” anymore?

Part 2: The Greatest Games Ever Played

College football had a problem. Increasingly, teams were getting better and better and the sport was growing in viewership, yet there was an issue — the best teams didn’t play each other at the end of the season. There were two primary issues: one was the fact that there were two polls (the AP and Coaches polls) that made up the top team rankings, and the other was that the major “bowls” were contracted to be played by the top teams of the various conferences rather than simply pairing the best teams. For that matter, what was the best team? If the coaches and AP didn’t agree at the end of the season, were multiple teams the “official national champion” (as was the case in about 10 seasons prior to 2000)? Does it even make sense to stress so heavily to find the “best” team in a division (D1 college football) that has over 130 schools? But more on that later.

Eventually, the Bowl Championship Series was created in 1998, primarily to make sure that in the case that the top two teams in the country were undefeated, they’d get an opportunity to play eachother rather than their contractually obligated bowl opponent. Originally, there was a rotation of the most prestigious bowls which would host the “BCS National Championship Game”, but this eventually changed, of course, to cater to increasing viewership and preserve the legacy of the four traditional major bowl games, which gained status as “BCS bowls” — the best of the rest.

If you were a sports fan that wasn’t glued to a TV on January 4, 2006, as 22% (!) of American households were, boy, I feel bad for you. I grew up a Southern California sports fan as I was born too late to enjoy the Cowboys dynasty of the 90s that my father preferred1, but became sentient just in time to experience the Age of the Running Back with my own hometown player LaDainian Tomlinson. Just to the north was Reggie Bush at USC, who was perhaps the most electrifying college football player of my lifetime2. Prior to this title game at the Rose Bowl (of course, it had to be there), USC had won 34 straight games off the backs of Bush and Matt Leinart, a Heisman winner in his own right. Up against them was a Texas squad who had won 19 straight games themselves, including the previous year’s Rose Bowl, led by Vince Young, who was perhaps the second most electrifying college football player of my lifetime. Yep, they went head to head, with USC as 7 point favorites.

There’s nothing I can say about this game that hasn’t been said already. It’s pretty much universally acknowledged as the greatest college football game ever played, both in terms of aesthetic appeal (it’s the freaking Rose Bowl) and in how back-and-forth and tense the game was. I’d recommend watching it, or at least the game-winning drive, if you haven’t.

The 2006 Rose Bowl is obviously the zenith of the BCS era. The system put together to remove the entrenching of teams, ironically enough, from the Rose Bowl succeeded in doing so and created the matchup that will undoubtedly remain the best of all time in the heads of anyone who witnessed it. But there was a slight flaw with the system, that would only continue to reveal itself over the coming years. You see, Texas and USC were historically strong CFB schools that came from “Power 5” conferences, which, back then, were fairly regional, but denoted a certain “strength” over non-Power 5 teams. These conferences were the SEC (of course), Big 10, Big 12, Pac-12, and ACC. The BCS ranking system, in an effort to systematize and “fairly rank” the top teams in the country, combined the two human polls with computer polls to spit out a “balanced” ranking. The argument became that P5 schools, due to historical performance, were weighted as stronger than non P5 schools whether or not that was the case. Which brings us to the second greatest game of all time: the 2007 Fiesta Bowl.

A curious trend started to emerge in the 2000s. A decidedly non-powerhouse school from the Western Athletic Conference, Boise State, started to put together teams with tremendous win-loss records by winning over 90% of their games from 2002-04. This culminated with a perfect regular season in 2006, vaunting them into the upper crust of the BCS rankings. The only other undefeated team was #1 ranked Ohio State, but Boise State was all the way down at number 9 behind 3 two loss teams. Ohio State ended up getting crushed by Urban Meyer’s Florida team (though there was a fair bit of polling controversy as to how they ended up in the title game), while Boise State was paired off against 2-loss, 7th-ranked Oklahoma (led by Adrian Peterson, another all-time-great running back.) Oklahoma was the favorite by 7.5, but Boise State built up a decently sized 21-10 halftime lead, which turned into a back-and-forth fiesta as Oklahoma stormed back, and both teams put up 22 points in the final minute and a half to end up tied at 35 going into overtime, with Boise State scoring from a 4th-and-18 at their own 50 on the last play of the game. Oklahoma scored a touchdown with the ball first in overtime, putting the pressure on Boise State to match them. After a tough couple series, Boise State scored a touchdown. But instead of kicking the extra point, they decided to go for two. What followed is one of the most famous plays in college football history — the Statue of Liberty.

Two years in a row, the BCS had actually fulfilled its lofty aims — it delivered the best true 1 vs 2 match in history, and gave us an extremely balanced, tense affair between properly matched top teams from different conferences. But the question that would eventually destroy it reared its head, one that the BCS system couldn’t really resolve: What do we call undefeated teams outside the top 2? Certainly, Ohio State and Florida had played tough schedules to reach the top, and the format necessitated that at most they’d flip-flop, but #3 LSU and #4 USC both had two losses. Boise State was the only undefeated team in all of college football — but because they weren’t P5, they ended up number 5.

Part 3: Capitulation

After the peak viewership of the 2006 Rose Bowl, squabbling over money was bound to happen. The bigger conferences were getting massive cuts of the revenue while the smaller ones had put together a potent 4-1 record against them when they made it to the BCS, including another undefeated run by TCU in 2010. Add in some financial improprieties and growing discontent amongst all parties over the term “National Champions”, the 4-team-playoff proposal won out and the BCS was shelved in 2012 after a particularly moribund 21-0 Alabama victory over LSU, a repeat of an already decisive regular season matchup.

At its core, though, the BCS worked. It delivered great matchups year after year, pairing close teams and delivering iconic games with close results. The failure was probably in the attempt to systematize a sport that doesn’t really lend itself well to rankings — inter-conference play was fairly limited and had a culture of being used as a tune-up for the intra-conference play that mattered (which went horribly wrong in the case of Appalachian State vs Michigan.) How exactly do you rank strength of schedule when the same teams play the same rotations again and again?

It didn’t make sense to divert from the intra-conference rivalry culture either. Fans of the Iowa football team do not care to play against Stanford or Texas A&M outside of a bowl game — they’re in it for the year in, year out matches against their in-state rivals Iowa State and their historical rivals that they’ve played against for decades. It’s a point of pride each year in a college town when you beat the college that’s had your number for a few years, or take out the Big Ten Big Shot team and spoil their major bowl chances. In some cases, that upset is all those college teams have to look for. The beauty of the BCS was that it gave a veneer of process over a sport that didn’t need process — it was fun the way it is. Who could forget the iconic run of a Colt Brennan or a Graham Harrell putting up insane stats in what would end up as the peak of their sports careers? Why did everything need to be about the illusion of meritocracy, rather than enjoying it for what it was — younger athletes having a great time buying into tradition and being supported by longtime local and alumni fans?

I was hesitant of the playoff proposal, especially when I found out that the teams would be selected purely by committee. For one, it kind of sucked the air out of finishing third or fourth — the semi-final bowl games didn’t really feel like a bowl. It also subsequently devalued the other major bowl games. Outside of the title game, one could argue that winning the Rose Bowl was equally as prestigious as winning the Fiesta, Orange or Sugar. No matter what, all those games were not coming along for the playoff ride. Lastly, I suspected that the inherent bias that existed towards major schools would become even more entrenched, creating a sort of talent funnel towards the teams most likely to make the playoffs each year as they consequently made more and more of them. What happened was even worse.

Part 4: Draining the Carcass

Immediately, things did not go as planned. Turns out, there’s very rarely 4 evenly matched teams in college football. On a good year, you have three; on an average year, you have two; and on some occasions, there’s just one team clearly better than everyone else (good lord, that Burrow/Jefferson/Chase LSU team was absolutely filthy.) This led to a lot of the semifinal matchups being straight up blowouts — in fourteen games, the average margin of victory is about 21 points, with only 3 being decided by single digits. A recurring cast began to emerge — Ohio State, Alabama, Clemson, Oklahoma, and Georgia regularly made it to the playoffs, with the occasional appearance from another major conference team. Recruits quickly noticed — the Alabama that won titles with Saban suddenly became 3-deep with five star talent across the board, making them into an offensive powerhouse as well as their traditional defensive setup. No longer were the Michael Crabtree’s of the game going to Texas Tech — for multiple years, Alabama and Ohio State were stacked with multiple first round WRs. In the past decade, Alabama’s offensive talent might have been higher touted going into the draft than their defensive for almost half the years. Hell, they’ve even started producing NFL Quarterbacks! Furthermore, none of the title games were really all that good either. Outside of the Watson-to-Renfrow final play to win the game, none of the others really had iconic moments down to the wire, and again, a large chunk of the games (66%) haven’t been close at all, with Georgia winning by 58 points last year on their way to covering the game Over/Under of 63 themselves. The playoff system has utterly failed, and yet, they want to expand it more. After all, viewership keeps going up, so why wouldn’t they give the fans what they want?

Part 5: Total Systemic Destruction

Look, by no means am I a person that thinks that there’s any sanctity to the “student-athlete.” As evidenced by innumerable numbers of players that peaked in college and didn’t get a single cut of the revenue and enrollment that schools minted off of (including Bush, Johnny Manziel, Tim Tebow, and more), the NCAA system was rightly forced to concede that banning players from making money off their name, image, and likeness (NIL) was totally wrong when everyone else was profiteering off them.

But there was a sanctity present, in that college football was an amateur sport, not a professional one. Clearly it is a pipeline to professional football, but it’s not an outright semi-pro league. The value of the sport was always in the historical matchups between the kids who went to your alma mater or represented your college town beating the other team that they’ve always played. This is partially why literally everyone who has been to a football game live says that college is way better — the quality of play is nowhere near as good as the NFL, but the fans care way more. I’ve been to a Brown vs Yale game where the tiny liberal arts kids are doing kegstands, Big Ten tailgates where the entire college town comes out to party and the streets smell like beer all Sunday, and the 2021 Red River game at the Texas State Fair which was without a doubt one of the most incredible sporting events I’ve ever seen, where Caleb Williams became a household name after turning around what was purportedly a Texas drubbing during the second half. Neither of these teams belong in the SEC, and Stanford doesn’t belong in the ACC. Who is going to be interested in a Stanford vs NC State regular season game? The shameless chasing of TV revenue has completely balkanized the previously logical regional conference system. Add on the fact that there’s no longer a transfer cooldown of sitting out one year, and all of a sudden players are shifting college teams like NBA players demand trades. Somehow, the aforementioned Caleb Williams now plays for USC, which is now a Big Ten school. I don’t blame players for grabbing the bag, of course, especially after that documentary revealed how much Johnny Manziel missed out on. But what happened to college football is what everyone was afraid of with the ill-fated Super League in soccer — the game ceases to be a game first but rather a vehicle to maximizing revenue by stuffing commercials into every nook and cranny possible3 to justify the insane TV deals and by pushing gambling.

It’s harder and harder to see what “college” means in college football other than an indication of the colors a player might wear for one year before he breaks out and goes to LA or the SEC to grab a bag. Maybe we’ll see something like franchise tagging for scholarship offers — wouldn’t that be hilarious? All I know for certain is that expanding the playoffs won’t do anything other than further trivialize bowls and cause more blowouts. Sometimes, you gotta just accept that a game for kids played between them is precisely that, and nothing more. Long live the BCS.

Later, I would disavow the Chargers for my second favorite team historically, the Cowboys, over their eventual move to LA (which was rumored as early as 2013, and pretty much guaranteed to happen by 2015.) Tony Romo and Terrell Owens remain as some of my favorite players, and it was a travesty that T.O. wasn’t a first ballot hall-of-famer.

In fact, nearly a decade later, I almost went to USC solely because of those 2000s football teams.

I’ve recalled multiple big name SEC matchups going well over 4 hours in regulation due to commercials and first-down stoppages