Suing over Irrational Exuberance

Malt Liquidity 108

Beyond Profit

I remember having an Impossible burger the first day it was commercially sold in a restaurant, at Momofuku Nishi in Chelsea. Having grown up vegetarian (and quit a few years prior), I sort of got the sense that if it had existed right before I quit, I might have never become non-vegetarian, as I quit solely to taste an In-N-Out burger and never looked back. The burger, priced at around $20 (which, back in 2016, was actually pricy for Manhattan) was novel in that it mimicked a “real” burger shockingly well. But immediately after finishing the meal, a thought occurred — what, exactly, was the target market here? Vegetarians and vegans don’t want to taste meat while non-vegetarians weren’t going to spend 2-3x the price of farm-raised meat en masse due to “environmental concerns” because, after all, the production cost of lab-grown meat was much, much higher than animal meat. And certainly, the market of “nonvegetarians who became vegetarians and miss meat” is miniscule compared to, well, “normal” eaters.

Of course, none of this mattered when BYND IPO’d in 2019, being one of the rare stocks where the mania hit before COVID markets.

If you weren’t following markets back then, it’s hard to contextualize how insane this stock price movement was. After the initial hype, BYND rocketed up to a market cap of $14 billion on revenue of just 300 million.:

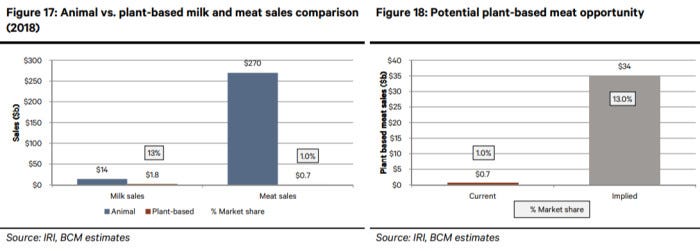

You might think, well, at least their revenue was doing multiples year over year. But the issue was more in the patent ridiculousness of the marketing materials. Much like a pitch deck for an app might cite “everyone with a smartphone” as the TAM, BYND did the same with consumers of non-dairy milk:

Beyond Meat’s own IPO marketing invited the use of non-dairy milk as a case study. By 2019, milk alternatives were already popular. Plant-based meat looked like the obvious next big thing, US sales having grown by 24 per cent in dollar terms in 2018 while dislodging less than 1 per cent of a much bigger theoretical TAM. These charts are from a 2019 vintage Berenberg note:

The thing is, meat is not milk. There’s a valid medical reason people would shy away from milk, while vegetarianism is primarily an ethical preference

Thirty to 50 million Americans are lactose intolerant. 80 percent of all African-Americans and Native Americans are lactose intolerant. Over 90 percent of Asian-Americans are lactose intolerant, and it is least common among Americans with a Northern European heritage.

which was reflected by the revenue growth sputtering as time went on, because a vague sense of wanting to cut meat consumption isn’t likely to overcome this sort of price premium;

Beyond burgers are at a steeper markup than an apple at Dean & Deluca.

So, naturally, shareholders sued:

Beyond Meat Inc. executives and directors were sued for fiduciary breaches, unjust enrichment, gross mismanagement, and negligence for allegedly making misleading statements about the plant-based meat substitutes company’s production capacity and partnerships.

The defendants misrepresented the strength of partnerships with brands like Taco Bell and Pizza Hut, and overstated the ability to scale production, according to the complaint filed Thursday in the US District Court for the Central District of California.

The reality of the public company (and why so many attempted to stay private as long as possible when funding was flush) is that you will be sued whenever anything craters the stock price. Forward guidance too optimistic? Lawsuit. Incorrect prognostications? Lawsuit. Something goes awry tanking the share price? Lawsuit. I really empathize with company executives who are running a business that’s headed straight for the iceberg, because what can you do other than be positive about, I dunno, Beyond KFC Nuggets (which apparently were inedible)? Investors who are salty because they bought shares at shitty valuations bringing lawsuits are why it’s so hard to get a transparent answer from an earnings call. Simple tip — if you want to compare forward guidance to reality, just look at the debt. The debt market never lies.

In this case, the lawsuit highlights that executives sold in 2021 when the price was high and their positive statements contradicted the reality that the market would assess after coming down from its mania:

When Beyond Meat’s directors solicited a proxy statement for 2021, they “willfully or recklessly made and/or caused the Company to make false and misleading statements to the investing public,” shareholder plaintiff Kimberly Brink says in her derivative suit.

Meanwhile, former Chair Seth Goldman profited $24.1 million and director Raymond Lane made $10.5 million in proceeds from insider sales, she said in the complaint.

Beyond Meat announced a 12% to 25% reduction to its third quarter net revenues outlook in October 2021, sharing with investors that the company’s expenses were continuing to rise. This disclosure prompted a 12% decrease in Beyond Meat share price, which fell from $108.62 to $95.80 per share in just one day, according to the complaint.

Here’s the thing — executives cannot just sell on a whim. They have to pre-plan and file their sales before they hit the market. If the price happens to be randomly high, due to investors bidding it up, their sales will look good! Certainly there is some discussion to be had over 10b5-1 plans,

The empirical tests indicate that Rule 10b5-1 plan sales by CEOs are more likely at firms that face greater litigation risk. Furthermore, plan trades are more likely during the 40 trading days before a quarterly earnings announcement and are less likely during the 40 days after such an announcement. This evidence is consistent with CEOs choosing to trade under plans when the likelihood of facing accusations of trading on material non-public information is greater. It is also consistent with CEOs using Rule 10b5-1 plans to sell their shares during corporate trading blackout periods, which typically prohibit trading before earnings announcements.

but I generally think there needs to be some fluidity for insider shareholders to profit, otherwise the incentives are not aligned between investors and management. This behavior is not indicative of trading on insider information, necessarily, as it’s simply logical to file for sale before an uncertain event like earnings, where the market reaction is totally unpredictable. A simple rule I follow is this:

Insider buying can only mean one thing — they think the stock will go up. Insider selling, on the other hand, can happen for a myriad of reasons — reducing exposure, moving to cash to fund a purchase, tax harvesting, and more. As such, it’s harder to assign meaning to insider sales, especially when they are cloaked in premeditation.

The signs were plainly obvious from 2019 onwards — sometimes a bad investment is, well, bad. Sour grapes shouldn’t provide standing for a shareholder lawsuit.

Well, this is ridiculous

Every time I think I can’t be surprised anymore by some nonsensical crypto-related story, another one rears its head:

The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged Richard Heart (aka Richard Schueler) and three unincorporated entities that he controls, Hex, PulseChain, and PulseX, with conducting unregistered offerings of crypto asset securities that raised more than $1 billion in crypto assets from investors. The SEC also charged Heart and PulseChain with fraud for misappropriating at least $12 million of offering proceeds to purchase luxury goods including sports cars, watches, and a 555-carat black diamond known as ‘The Enigma’ – reportedly the largest black diamond in the world.

Something I’ve always wondered, as I’ve noted before, is

If you promise high returns on investment, you kinda should have at least an idea of what you’re going to do when people ask for their money back. Otherwise, you’re basically guaranteeing yourself jail time for a little bit of fun. These purchases are just appalling too. Vehicles and jewelry generally don’t hold value well.

Yet this pattern happens again and again:

According to the SEC’s complaint, Heart began marketing Hex in 2018, claiming it was the first high-yield “blockchain certificate of deposit,” and began promoting Hex tokens as an investment designed to make people “rich.”…

Heart also allegedly designed and marketed a so-called “staking” feature for Hex tokens, which he claimed would deliver returns as high as 38 percent. The complaint further alleges that Heart attempted to evade securities laws by calling on investors to “sacrifice” (instead of “invest”) their crypto assets in exchange for PLS and PLSX tokens.

Note that even Alameda Research, part of the biggest fraud of my adult lifetime, only promised a 20% guaranteed return.

Part of me feels this is almost entirely due to the human susceptibility to misunderstanding numbers and probabilities intuitively. I’ve met at most a handful of people who can truly “process” a 3% probability intuitively, or what a 7% return is. A common motivational phrase I’ve heard is to aim to improve “1% each day”, which sounds minute, yet, if annualized to 252 trading days in a year, would be well over 1000%. Not exactly feasible, is it? Even 7% is being generous in a frothy market state.

And yet, I’m consistently surprised at how many people fall for this stuff and how lucrative it is. It’s something I consistently think about regarding podcasts — there are an infinite amount of them, yet when you have Facebook hitting 3 billion users, you are still seeing a dearth of content for people to consume! It’s mind-boggling to think about the scale of these things.

So please, when you look at an advertised investment return on a product, take it with a grain of salt unless it’s a coupon or a money market fund. Reality is not so kind to prognostications that aren’t guarantees.