Paradigm Shift 2075

Malt Liquidity 105

One of my favorite quotes to remember about sell side research comes from David Einhorn, of all people:

This statement should be trivially observable on any given day in modern markets, with “upgrades” and “downgrades” comically following stock prices that we all know don’t really make sense. For example, SVB right as it was getting liquidated had precisely 1 “sell” rating:

My point isn’t that research analysts are useless — indeed, if you actually read their reports, they do actually comb through the financials that I’m much too lazy to do myself — but that none of these people have skin in the game or any real reason to put anything other than a buy rating on a stock, due to the fact that research is generally marketing for the banks to be able to pitch trades to clients (and then collect txn fees.)

(Note: yes, I am aware of the existence of MIFID regulations that forced the unbundling of research as a trade-incentivizing service, but that’s beyond the scope of this post.)

So when I come across a report from Goldman prognosticating how the world looks in 2075, I take it with a heavy degree of skepticism. Bankers are not sci-fi writers, nor are they any good at generating an actual future outlook. Just take the insane numbers McKinsey and Citi were putting out regarding the metaverse:

McKinsey predicted that the Metaverse could generate up to "$5 trillion in value," adding that around 95% of business leaders expected the Metaverse to "positively impact their industry" within five to 10 years. Not to be outdone, Citi put out a massive report that declared the Metaverse would be a $13 trillion opportunity

Keep in mind that this Citi report was generated by 12 senior bankers and 25 analysts. How can you take these people seriously?

Far from being worth trillions of dollars, the Metaverse turned out to be worth absolutely bupkus. It’s not even that the platform lagged behind expectations or was slow to become popular. There wasn’t anyone visiting the Metaverse at all.

The sheer scale of the hype inflation came to light in May. In the same article, Insider revealed that Decentraland, arguably the largest and most relevant Metaverse platform, had only 38 active daily users. The Guardian reported that one of the features designed to reward users in Meta’s flagship product Horizon Worlds produced no more than $470 in revenue globally.

Of course, a spending blitz like this would have let to the firing of any other CEO a long time ago, but as I’ve noted before, it’s impossible to push out founders due to how favorable the equity structure given to them was. And, of course, Facebook immediately pivoted to the next hype cycle — generative AI.

…the Metaverse was officially pulled off life support when it became clear that Zuckerberg and the company that launched the craze had moved on to greener financial pastures. Zuckerberg declared in a March update that Meta's "single largest investment is advancing AI and building it into every one of our products." Meta's chief technology officer, Andrew Bosworth, told CNBC in April that he, along with Mark Zuckerberg and the company's chief product officer, Chris Cox, were now spending most of their time on AI. The company has even stopped pitching the Metaverse to advertisers, despite spending more than $100 billion in research and development on its mission to be "Metaverse first." While Zuckerberg may suggest that developing games for the Quest headsets is some sort of investment, the writing is on the wall: Meta is done with the Metaverse.

What follows is probably more speculative than anything I actually think about. I don’t see much value in making long-term, unfalsifiable prognostications because the universal truth of speculation is that when you minimize your hold time, you minimize risk. What does it even mean to say “India superpower by 2020”? Were you going to wait 12 years to judge this prediction, or would you just ignore it and move on? Consistent “macro tourism” has a “Ron Paul advertisement for selling gold” feel to it, in that we can’t get any real use out of it, but it’s annoyingly, perpetually there. Without further ado, let’s dive in.

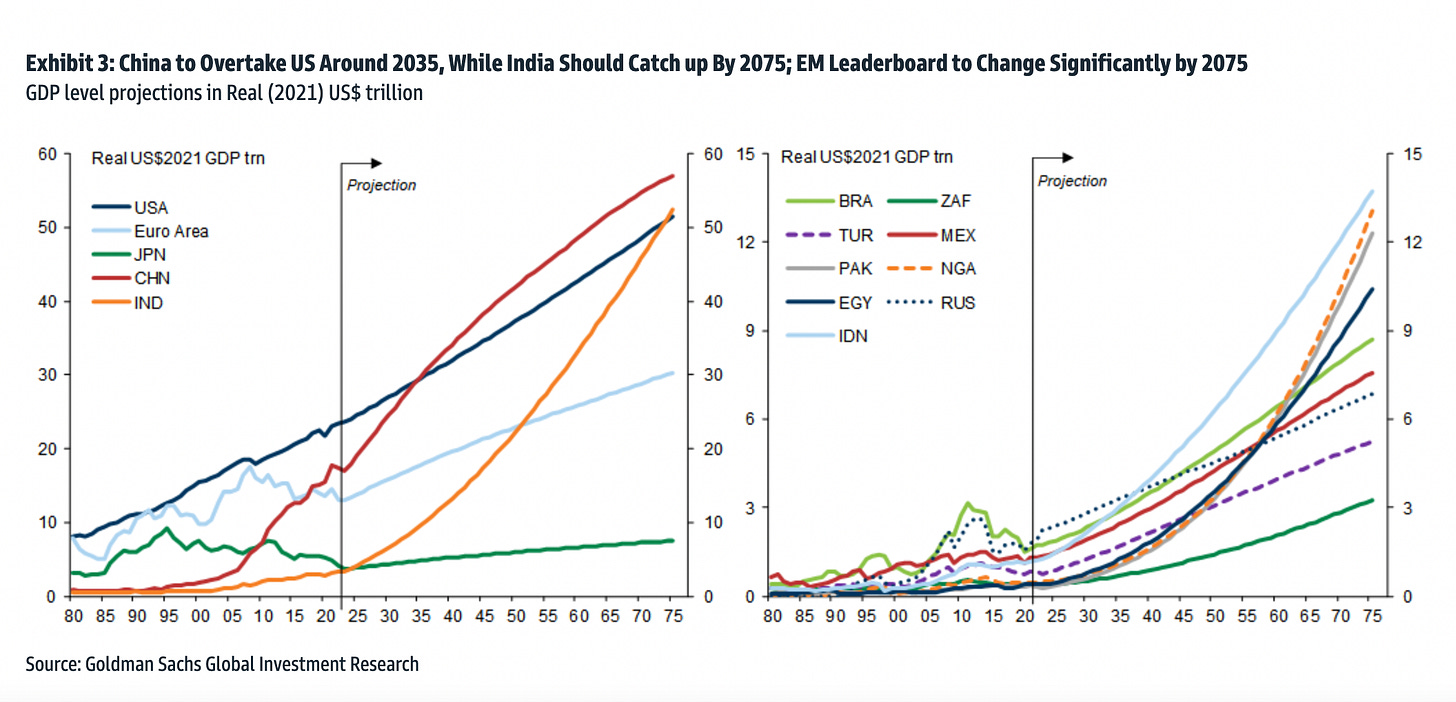

We recently set out long-term growth projections for the global economy, covering 104 countries out to the year 2075. We expect EM growth to continue to outstrip DM over the remainder of this decade (3.8% vs. 1.8%). In 2050, we project that the world's five largest economies (measured in US$) will be China, the US, India, Indonesia, and Germany. By 2075, China, the US, and India are likely to remain the three largest economies and, with the right policies and institutions, seven of the world's top ten economies are projected to be EMs…

Openness to trade and capital flows is a necessary condition for the successful development of capital markets. Of the many risks to our projections, we view the possibility that populist nationalism leads to increased protectionism and a reversal of globalisation as the most significant.

If you look at how Goldman is doing their projections, you get the idea that it’s some very basic Excel modeling:

Part of my hesitancy to ever utilize financial models is that a core belief of mine is that growth is not linear or straightforward, and one of my genuine worries is how exactly we square away the assumption of infinite growth that our financial system is based on. Thus the economic growth narrative relies on the growth of the total addressable market itself, by creating consumers through lifting them out of poverty and giving them disposable incomes, or through raw population growth itself. I find myself disagreeing that protectionism and skepticism of globalisation is the biggest threat — from a raw probability point of view, the global trend of insufficient childbirth to replace our currently aging population is much likelier to cause issues in the immediately foreseeable future than protectionism. The reason for this is explained by China’s remarkable growth story since the mid 2000s — if you build the population, they (developed companies) will come. Need I recount the extreme contorting Hollywood studios have done to access the Chinese market, let alone what big tech attempted to do, by straight up allowing Chinese tech to replicate and modify their IP for their own benefit? The Chinese growth story doesn’t work without protectionism, by tantalizingly dangling the honeypot of “surely you will access our market if you do this for us!” I don’t see how this changes for China, because if they ever do totally open up for business, it will only be to the US’ benefit.

From an expected value point of view, though, the biggest risk would probably be that of nuclear annihilation, due to the sheer destructive power that the erosion of MAD would cause. I think this is an infinitesimal probability, but it is non-zero in our age of wary detente between world powers and an ongoing proxy war with no end in sight. I truly believe that the psychopaths that would nuke everyone on their way out will never be able to build the requisite social coalition to acquire the codes, and the people that do acquire the codes, even if sociopathic, would not take out the social coalition that helped them get to that point, but I could be wrong.

Our projections imply that EMs' share of global equity market capitalisation will rise from around 27% currently to 35% in 2030, 47% in 2050, and 55% in 2075. We expect India to record the largest increase in global market cap share – from a little under 3% in 2022 to 8% in 2050, and 12% in 2075 – reflecting a favourable demographic outlook and rapid GDP per capita growth. We project that China’s share will rise from 10% to 15% by 2050 but, reflecting a demographic-led slowdown in potential growth, that it will then decline to around 13% by 2075. The increasing importance of equity markets outside the US implies that its share is projected to fall from 42% in 2022 to 27% in 2050, and 22% in 2075.

The EM growth story will always revolve around the mobilization of the two largest populations, of course. But what’s particularly interesting is that, while China’s pathway is pretty self-evident, India’s path forward is far less demarcated. “India superpower 2020” became a meme for a reason — theoretically, it has the requisite population, educational infrastructure, and burgeoning industry to genuinely develop to shake up the world order, yet if you look at the graph posted above, its growth rate was far below the comparable Chinese, and Goldman’s narrative depends on a rapid exponentiation of their growth curve. (Let’s ignore the random reversal of Japan’s fortunes, for the time being, which should point out how silly this entire publication is.) So what exactly is holding it back?

This relative shift from China to India reflects two factors: India's stronger demographic outlook and a more rapid pace of GDP per capita growth (from lower levels).

Goldman’s attribution of more rapid growth doesn’t explicitly point out what I mentioned earlier, but it seemingly follows along the same lines — India does reproduce at a replacement level, while China reckons with the effects of one-child policy and a disillusioned younger workforce that “lies flat.” The problem, of course, is that not all childbirth is created equal; it’s essentially a known relationship that a higher socioeconomic status leads to reduced childbirth. Or, to put it in a more amusing way, I always refer to the opening scene of “Idiocracy”:

It’s kind of sad how quickly the satire became our stark reality, isn’t it?

Adding in the significant amount of brain drain as the highest skill employees migrate to the West, we get a clearer picture that the rosy demographic projections of India don’t acknowledge the skew that exists in reality, where the highest achievers, and potential industrialists, are less likely to actually remain and induce this growth. Beyond this, however, I think the biggest risk to India is unreliable monetary policy. One of the biggest controversies in recent times was the demonetization incident, where, overnight, many outstanding 500 & 1000 rupee notes became invalid, and had to be exchanged for new issuances of those bills. The goal was purportedly to kill the “underworld”, untraceable use of cash to grease the wheels, and to push cashless transactions. What resulted was instant chaos, because in a country of 2 billion, the mass crowding mentality of “where’s my money” is simply not predictable. To be clear, I don’t think that experiment was negative in the doom-spelling way economists at the time predicted it would be — rather, I think the issue is one of key-man risk, similar to what I wrote about regarding the Korean bond fallout:

As the first due date for the bonds was approaching on Sept. 29, GJC was in talks to extend the deadline with BNK Securities, the underwriter for the bonds. Negotiating for such an extension is a tense affair but a relatively common one. GJC was close to buying itself a three- or four-month reprieve, by prepaying BNK four months’ worth of interest that it would additionally owe by extending the due date.

…on Sept. 28, Gangwon’s newly elected conservative governor, Kim Jin-tae, announced that he would not honor the government’s guarantee. Instead, GJC would enter into bankruptcy, meaning that creditors would receive pennies on the dollar. BNK Securities declared a default on the GJC bonds and sought assurances that Gangwon would pay back the 205 billion won, but the government gave only a vague promise that it would honor the guarantee without giving a specific date. By mid-October, the GJC bonds were downgraded to junk status.

While the monetization hullaballoo did result in increased mobile banking and a more transparent financial system, the fact of the matter remains that when one person can decide to do something on a whim and heavily influence the apparatus that is supposed to dampen societal volatility, you never know when the carefully constructed bureaucracy can be upended. For better or worse, India is definitely under Modi’s control for now and will be under the control of whoever follows him. One gets the feeling of a mild animus and skepticism towards standardized Western economic thought on topics like inflation targeting and monetary policy. This isn’t bad, it’s just not nearly as predictable as Goldman would portray it, and populism isn’t really the right way to describe this type of risk.

Do our projections that EMs’ share of global equity market cap will rise at the expense of DMs imply that long-term investors should overweight EM vs DM equities? Not necessarily.

To the extent that the growth of EM capital markets comes from the equitisation of corporate assets – and we expect this to be the major driver – this does not have a clear implication for the performance of equities themselves.

That said, we expect EM equities to outperform DM equities in the longer run for other reasons: namely, the combination of stronger long-run earnings growth and multiple expansion, as risk premia fall.

Finally, we come to the actual point of such a publication, which aims to answer one question: “Should I allocate more to EMs than to US indices?” While Goldman demurs in a manner fitting of a national politician, I would argue that this is a resounding no, because I don’t believe exposure through the stock market is trustworthy enough. Recall what I wrote about ADRs a couple years ago:

Now, with Congress finally acting, we are seeing some sort of reversion, where the market is finally realizing that owning Chinese stocks also means you are long their compliance with both the CCP and American listing institutions…

Traditionally, the purpose of going public was to raise money for expanding the business when private funding dried up. Now that private money is available in much larger quantities (and the compliance is lower), companies are staying private much longer. But what exactly are Americans buying publicly listed shares of Chinese Telecoms for? These companies are cash flow machines, and there is no logical rationale to argue the money raised in US listings somehow contributes to the “expansion” of these state-approved businesses. In some way you are “exposed” to the company, but given that these companies can just be delisted, shouldn’t these shares be trading at a discount, rather than the roughly 4-7% premium as evidenced by the price action?

The China “what exactly is an ADR giving you the right to” scenario is not unique — Indian markets, for example, are fairly inaccessible to foreign investors as well, as I noted with the Hindenburg Adani situation. Rather, the best way to invest in these countries, is, well, to do business in them. I trust a VC fund raised specifically to seed-fund Indian companies far more than I trust an ETF of the “Nifty 50”, which is also easily my favorite name for a stock index. Naturally, those funds won’t be publicly traded.

In conclusion, Goldman’s report depends on a lot of assumptions, but the biggest one seems to be that everyone globally magically transforms their financial system into one resembling what we have in the US nowadays. Needless to say, I find this kind of ridiculous. Always take your sell-side research with a grain of salt.