Something that is constantly glossed over is that most transactions take place with other people’s money. Companies buy other companies by raising debt or using equity that’s valued by prior purchases, bank lending is dependent on deposits, and every line of credit issued with a card fronts your purchase every time you tap your card (which is why I recommend transacting with a credit card over a debit card — if there’s a fraudulent charge, it’s AmEx’s money that’s being skimmed, and they’ll deal with it immediately as opposed to a debit card where your money’s been skimmed.) Most of the asset management industry is predicated on taking in funds from other individuals and investing them for a cut. It’s why the concept of “skin in the game” is so powerful, and when there is an insufficient personal stake at risk, things can get very out of hand very quickly:

SocGen states that Kerviel was assigned to arbitrage discrepancies between equity derivatives and cash equity prices,[15] and "began creating the fictitious trades in late 2006 and early 2007, but that these transactions were relatively small. The fake trading increased in frequency, and in size".[16] Bank officials claim that throughout 2007, he had been trading profitably in anticipation of falling market prices; however, they have accused him of exceeding his authority to engage in unauthorized trades totaling as much as €49.9 billion, a figure far higher than the bank's total market capitalization. Kerviel tried to conceal the activity by creating losing trades intentionally so as to offset his early gains.[17] According to the BBC, Kerviel generated €1.4 billion in hidden profits at the beginning of 2008.[18] His employers say they uncovered unauthorized trading traced to Kerviel on 19 January 2008. SocGen then closed out these positions over three days of trading beginning 21 January 2008, a period after which the market experienced a large drop in equity indices, and losses attributed are estimated at €4.9 billion ($7 billion).

SocGen claimed Kerviel "had taken massive fraudulent directional positions in 2007 and 2008 far beyond his limited authority"[19] and that the trades involved European stock index futures.

The entire “rogue trading” problem and why the Volcker rule was put into place was to correct this risk asymmetry of individuals trading bank deposits (read: other people’s money), where if you bet big beyond your limits and won, you’d get a huge bonus, and if you lost, you’d get fired and just move to another role at another bank. This is why I highlight debt as the most important instrument of the financial system:

However, when boiled down to its simplest elements, the system is essentially made up of three pillars: equity, currency, and debt. Equity provides liquidity to hope. Currency provides liquidity to bargaining — our transactions have to be denominated in something. The most important pillar, and what underpins it all, is debt, which provides liquidity to trust. The systems of law and government provide a safeguard of enforcement to trust, but trust without liquidity cannot scale — there is no society without it.

Connecting these pillars is the banking system, which facilitates the liquidity provision.

The point of this little diatribe is that when one forgets or disregards that what is owed must be repaid, and what is managed is not yours, it’s not borrowing — you’re just spending someone else’s money. Let’s look at what happens to a recurring delinquent borrower:

Last week Argentina struck a deal with Beijing to tap nearly $3 billion in yuan from a currency swap line the two countries renewed in June. The announcement, in which China is playing the lender of last resort for Argentina, came two days after the International Monetary Fund reached a preliminary agreement with Buenos Aires to unlock access to $7.5 billion. The IMF said the money is “intended to support Argentina’s policy efforts and near-term balance of payments needs, including obligations to the Fund.” In other words, the fund is giving money to its “client” so that the client doesn’t go into arrears on its $44 billion debt to the fund.

The arrangement needs IMF executive board approval, which may come later this month. Meantime, Argentina has used the China loan—and help from Qatar—to stay current with the IMF.

Incredible. It’s a credit card balance transfer routine at a global scale. You really gotta hand it to the modern financial world — cans can perpetually get kicked down the road. It’s hard to believe articles like this were being written just 6 years ago

Argentina sold $2.75 billion of a hotly demanded 100-year bond in U.S. dollars on Monday, just over a year after emerging from its latest default, according to the government.

The South American country received $9.75 billion in orders for the bond, as investors eyed a yield of 7.9 percent in an otherwise low yielding fixed income market where pension funds need to lock in long-term returns.

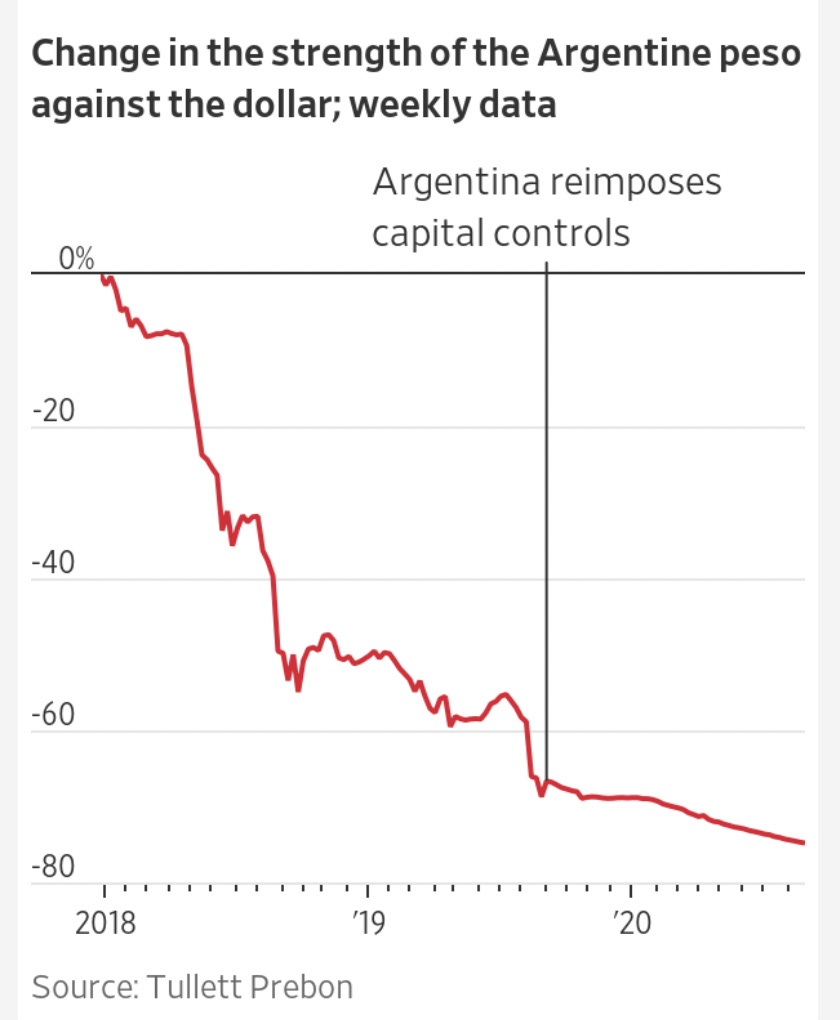

which ended predictably, because why the hell are you buying 100 year debt from a country whose currency has collapsed 9 times in the prior 100?

An August restructuring guarantees that foreign creditors will get little more than half of what they were due on $65 billion of debt, including the 100-year bonds the government sold three years ago at the height of a decadelong emerging-markets boom.

I can tell you this — the asset managers buying those bonds weren’t doing it with their own money. When it’s a fund manager’s personal money, the results tend to look more like this:

Billionaire Paul Singer defeated the nation of Argentina today when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling allowing a subsidiary of his Elliott Associates hedge fund to dig into Argentina's bank records in search of assets to seize in compensation for some $2.5 billion in defaulted bonds and interest.

Yeah. They almost seized an Argentinian warship when it docked in Ghana:

The most dramatic moment in the dispute came in 2012, when Elliott made international headlines by attempting to take possession of an Argentine Navy vessel. The three-hundred-and-thirty-eight-foot ship, the Fragata Libertad, was reportedly hosting a hundred and ten naval cadets from several countries, sixty-nine members of the Argentine Navy, and a crew of two hundred and twenty. As the ship settled into the largest berth in the Port of Tema, in Ghana, a man appeared onshore wielding an order for the ship to be impounded. Argentina’s lawyers rushed to hire the best Ghanaian lawyer, Ace Ankomah, only to discover that he had already been retained by Elliott.

Most of the cadets left the ship, but the Argentine soldiers remained on board while the two sides bickered in court. At one point, according to someone involved in the case, a Ghanaian policeman arrived with a hydraulic crane and announced that he was going to board the ship. Weapons were drawn, and he backed down. Eventually, the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea invalidated Elliott’s court order, and the ship sailed away.

Elliott eventually made a ton on the purchase:

Argentina agreed to pay the company $2.4 billion, a 1,270-per-cent return on its initial investment, according to one analysis.

It’s hard to know what to exactly do in these situations. When an individual has run dry on their ability to borrow, they declare bankruptcy and have to scrounge by on a life with no credit line available for a few years. But when you’re a country, and your inflation is running above 100% due to over-printing currency that results in multiple exchange rates,

The purchase of dollars for travel abroad or to pay for imports also is done through the central bank. It has more than 10 official exchange rates, none of which reflect the market. The rate at the central bank for retail is around 290 to the dollar while in the black market the rate is about 565.

it’s not clear how you ever get off the endless doom loop of having to repay already-issued debt with newly raised debt until eventually you get a hyperinflated currency and everything starts at zero again. The Wall Street Journal cites Thatcher describing “socialist reality” as the reason why Argentina is stuck, but a new “business friendly” politician can’t change the direction of a ship that’s already run aground. We looked at this on the scale of a bank in Credit Suisse,

Turmoil begets more turmoil. Losses and scandals (and the occasional mysterious death) require constant restructuring and replacement of executives, who will all have different ideas on how to “recover” from the business, but the reputation loss is the real death sentence. Furthermore, how are they going to retain any remaining talent through their “bonus now pay later” structure in a bonus-driven industry? Admitting that business lines aren’t going well just shows even more incompetence which leads to more caution from potential clients which leads to even more business lines being shut down — it’s the death spiral.

and Argentina’s case doesn’t appear to be that different. The game is the game.

Comparing Argentina to Turkey is an interesting exercise, as foreign investment seems to be testing the waters once again:

Foreign investors, who have largely abandoned Turkish stocks in recent years, have pumped $1.6bn into the country’s equities market in the seven weeks to July 21, according to central bank data. The inflows have come as central bank governor Hafize Gaye Erkan, a former Wall Street banker who was appointed in June, has more than doubled interest rates in an attempt to rein in inflation, which is running at almost 40 per cent. Meanwhile, finance minister Mehmet Şimşek, a former deputy prime minister who is well-regarded by foreign investors, has boosted petrol and value-added taxes on goods and services. The move is part of an effort to cool an economy that went into overdrive after Erdoğan showered the public with giveaways, such as a month of free gas and wage increases for public workers, before May’s election, which he won.

Recall what I wrote about Turkey a little while ago:

Even after hyperinflation, a country can recover, like Germany did (twice.) But it requires “buying in” to whatever national currency develops in its place. If an alternate source of liquidity usurps the national currency, however, inherently monetary policy will fail — there’s no “central bank” of crypto (or any sort of debt facilitation a la perpetual bonds — this is the main flaw with decentralization as a concept.) If you’re a Turkey resident, you’re stuck between a rock and a hard place if you cannot leave the country financially and physically — you still need to pay your taxes and buy goods, but your financial interests are best served avoiding your national currency... In effect, a central bank that allows runaway inflation is essentially rugging its own population — the person with 3 million in Lira denominated assets suffers complete destruction, while the person with 30k in Lira denominated debt gets an effective reset. Everyone is back to square one.

The immediate takeaway from the Turkey situation is that stemming the tide of inflation requires very drastic interest rate action and attempts to shore up the money supply. Perhaps the difference is that Turkey seems to not be tapping the debt market to pay off international debts — the weird cacophony of Erdogan’s prior policy resulted in

an environment where, as a normal banking institution, you want cash deposits, you don’t want government bonds, and your clients don’t want either of these things.

which, notably, isn’t a debt balance transfer. Theoretically, severely shoring up the availability of credit and the currency supply could wrangle inflation to a manageable rate. It also helps to have, er, a sovereign state fund backing you:

Saudi Arabia has deposited $5 billion at the Central Bank of Turkey through the Saudi Fund for Development…

The move is "a testament to the close co-operation and historical ties" between the two countries and of Saudi Arabia's "commitment to supporting Turkey's efforts to strengthen its economy and to promote social growth and sustainable development", the fund said.

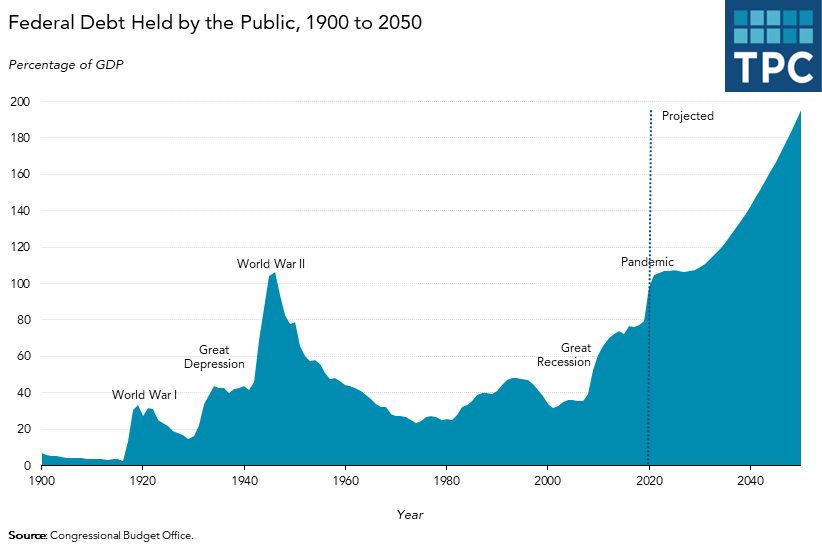

This is the core issue with the infinite growth assumption — if your debt comes due and you can’t pay it, you have to borrow more and use someone else’s money. I wonder what happens if there’s simply too much debt to kick the can down the road on, though…