Further Elaboration Required

In my 2022 year-in-review, I made some predictions for 2023, some of which deserve some further elaboration. I’d like to elaborate on two statements I made

bearish: ChatGPT

GOOGL will lag the aforementioned [AAPL,MSFT,AMZN]

in light of the news that Microsoft is looking to invest in ChatGPT’s owner, OpenAI:

Microsoft Corp is in talks to invest $10 billion in ChatGPT-owner OpenAI as part of funding that will value the firm at $29 billion…

Microsoft last year unveiled plans to integrate image-generation software from OpenAI into its search engine Bing. A recent report from the Information said similar plans were underway for ChatGPT as Microsoft looks to take on market leader Google Search.

According to Semafor, Microsoft will also get 75% of OpenAI's profits until it recoups its initial investment.

After hitting that threshold, Microsoft would have a 49% stake in OpenAI, with other investors taking another 49% and OpenAI's nonprofit parent getting 2%, Semafor said.

Reuters reported last month a recent pitch by OpenAI to investors said the organization expects $200 million in revenue next year and $1 billion by 2024.

First, even without looking at any numbers, it’s obvious why OpenAI needs to raise money — the cost of compute to run their services must be absurdly high. This was confirmed by OpenAI themselves:

OpenAI charges developers licensing its technology about a penny or a little more to generate 20,000 words of text, and about 2 cents to create an image from a written prompt.

It spends about a few cents in computing power every time someone uses its chatbot, Altman recently said in tweet…

This isn’t going to be a post on the future of AI or the replacement of human writers/artists, though I find ChatGPT to have the writing skill of an occasionally brilliant, precocious tenth-grader repetitively trying to fulfill a word-count requirement (though its ability to grep what presumably lies dormant on StackOverflow pages is pretty impressive.) What strikes me is that Microsoft’s proposed investment in OpenAI resembles a preferred-share agreement much more than it does a typical venture investment. We have talked a bit about the difference between equity and debt investments:

Equity investments are based on prognostication — you think that the future forward earnings of the company will be markedly increased compared to its current day earnings, so you invest. Debt investments are loans — I gave you money to grow your business, so you better pay me back with what you earn over time.

While Microsoft’s investment is clearly an equity investment bullish on the overall ability of OpenAI to facilitate the production of a minimum viable product, it’s interesting to me that the proposed terms highlight a right to 75% of OpenAI’s profits — it’s kind of like having the ability to exercise an option to cash out rather than essentially being required to plunge any revenue into reinvestment to potentially gain a positive ROI as you’d normally expect from a venture equity position. To me, this “fail-safe” implies a certain level of skittishness that OpenAI will ever produce anything of real go-to-market value. While $10 billion to buoy the cash burn is nothing to a company with $50 billion in quarterly revenue, it’s telling that software that supposedly will be folded into Bing presumably to destroy the Google search monopoly doesn’t get a carte-blanche check for that amount.

MSFT’s seeming skepticism of OpenAI, however, also implies to me that a) Google has no need to disrupt their current search protocol and b) DeepMind isn’t ready to put out a market-ready product either, else MSFT would probably be reacting with more desperation and less caution. While I believe Google is probably years ahead of what is publicly available through ChatGPT (since there’s no way they’ve poured this much money into DeepMind just to play board games), I also concurrently believe that since there’s no need to revamp search, their financial position in 2023 will revolve around cutting jobs rather than creating a new, lucrative vertical — I find it hard to believe they can further saturate their core products with even more ads, given that search is already basically unusable relative to its prior iterations. While Google has a stronger core business monopoly with search than MSFT with enterprise software, AAPL with hardware, and AMZN with online shopping (and cloud services to some extent), they are also notorious for spewing cash every which way to no real benefit (RIP Google Wave.) Furthermore, though Google’s own ecosystem is insulated from the ham-fisted control AAPL has over the revenues derived from its app store, AAPL will have an easier time encroaching on Google’s ad revenue than vice versa, as shown by their wanton destruction of META’s core business. In 2023, I think asset managers are going to be heavily focused on short-term signals that the prognosticated recession isn’t as bad as it seems — allocations to stocks will revolve around quarterly results, of which the expectations are already pretty low:

Analysts expect companies in the S&P 500 to report their first year-over-year decline in quarterly earnings since the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, according to FactSet. Fourth-quarter profits are projected to have dropped 4.1%, a sharp reversal from the more than 31% growth logged a year earlier.

Keep in mind what we discussed earlier about how most capital that flows into the market revolves around a lot more than day-to-day trading:

The vast majority of money that moves in and around the market is based on the philosophy that whatever is invested in will create future cash flow rewarding current shareholders, who hold a right to their share of the output… Note that these investors generally operate with a philosophy that they don’t want to react to day-to-day market movements. They are in it for the cash flow created over time and the movement in share price that will reflect that. So we want to focus on what will motivate them to decide that they want to demand liquidity and increase or downsize their positions.

Investing is driven by valuation — taking snapshots of a company’s performance over time and stringing them together to estimate future outlook. The question valuation asks is very simple: given an investment in a company, what do I own now, what am I expected to own in the future, and how much is it worth at present value?

While job cuts can provide a temporary boost to financials as the debt market no longer supports ZIRP-subsidized over-hiring, I really think that AAPL and MSFT are more streamlined, capital-efficient businesses and better poised to display justification for allocation from money managers in 2023, while AMZN is so beaten up compared to its peers (without facing the headwinds META does) that it looks like a logical, high availability hedge fund hotel to me.

Speaking of bad omens…

During the ZIRP years, value vs. growth was about as competitive as Wilder-Fury 2. When the cash output of the business didn’t really matter, what did matter was reinvestment potential. And so companies that were blatant frauds like NKLA or purely speculative ventures like LCID and RIVN all had blowout market debuts and run-ups — untethered to legacy gas-based vehicle businesses like a Ford and with regulatory frameworks heavily incentivizing EV purchases, every dollar taken in could be leveraged off of (due to the cheap debt plentifully available) and reinvested into the burgeoning market-of-the-future in EVs. However, to maintain the image of growth, certain targets needed to be hit — most importantly, deliverables. While NKLA languished due to being, well, a blatant fraud (and it’s astonishing this company isn’t zeroed out yet), RIVN was outputting vehicles — however, it seems like they are missing their targets:

Rivian Automotive Inc. fell short of its 25,000-vehicle production target for 2022, capping a challenging year for the electric-truck startup.

Rivian said in a regulatory filing that it produced 10,020 completed vehicles in the final three months of 2022, bringing its total for the year to 24,337. The company delivered 20,332 of those vehicles to customers.

Missing growth numbers means a lower market capitalization (the stock is down around 80% YOY) which means reduced equity to borrow against, and perhaps stricter debt-repayment terms if they were already linked to equity at higher valuations. Furthermore, a tougher environment ahead reduces the ability to retain top talent:

Several top executives at Rivian Automotive Inc., including the vice president overseeing body engineering and its head of supply chain, have left the EV startup in recent months, as the company exits a year in which it fell short of its production targets…

The company reported a net loss of $5 billion for the first nine months of 2022, and its cash pile fell to $13.8 billion at the end of September, down from $15.46 billion in June.

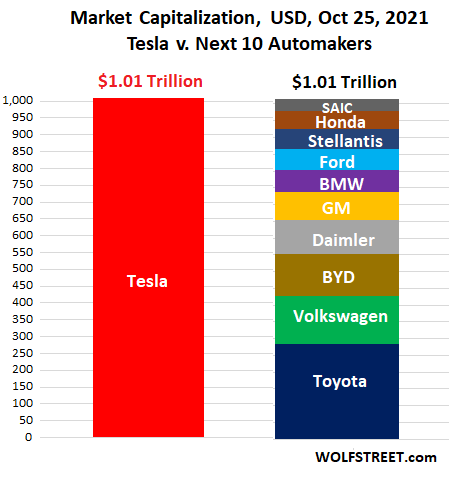

Something that I feel the entire startup and tech world took for granted for about a decade is that equity comp = guaranteed money. In some sense, this was true — due to the lack of incentive to invest in anything other than higher volatility securities during ZIRP, equity inflows seemed uncorrelated with actual business performance, most notoriously reflected by when Tesla was worth more than every large automaker combined.

Now that stocks have er, lost themselves, and “snapped back to reality”, the race to retain top talent lurches in favor, finally, of the cash-generating businesses — the long suffering Graham-ite tortoise. Until interest rates start to fall again, I am highly wary of any cash-losing growth operation that previously compensated employees with equity, and would keep a close eye on what their debt trades at going forward.