A Little Housekeeping

This post comes to you inspired by a thread on the Malt Liquidity Substack chat!

Looking forward to hearing from readers on there or on Twitter.

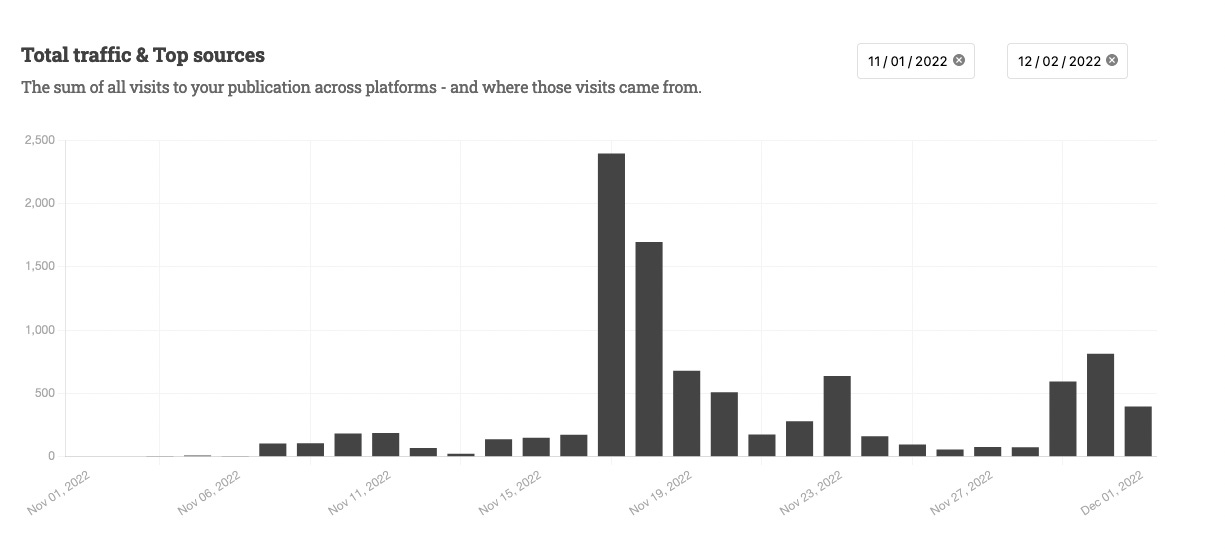

Also, we’ve had a pretty good month! If you’ve enjoyed the content, please consider sharing a link or forwarding an email. Thanks for reading!

The Perceptive Practitioner

In the past couple days, we’ve talked a lot about trading — shifting patterns and strategies and utilizing information about ourselves and market participants to generate trading ideas. But the trading community sometimes glosses over the biggest driver of inflows into the market — investment. While “funnymentals” don’t really help develop trading ideas, it’s important to understand the motivations that drive asset allocation and the fuel that contributes to the longer term upward bias of markets.

The vast majority of money that moves in and around the market is based on the philosophy that whatever is invested in will create future cash flow rewarding current shareholders, who hold a right to their share of the output. When this money sloshes around, it creates market impact, which in turn creates trading opportunity. Note that these investors generally operate with a philosophy that they don’t want to react to day-to-day market movements. They are in it for the cash flow created over time and the movement in share price that will reflect that. So we want to focus on what will motivate them to decide that they want to demand liquidity and increase or downsize their positions.

Investing is driven by valuation — taking snapshots of a company’s performance over time and stringing them together to estimate future outlook. The question valuation asks is very simple: given an investment in a company, what do I own now, what am I expected to own in the future, and how much is it worth at present value? This is what underpins the context of the hilarious screencap from an old SoftBank presentation that serves as my twitter banner,

where Masayoshi Son expressed confusion at the fact that at the time, the market valued the 25 trillion (in yen) in assets held against the 4 trillion in debt held at a 9 trillion market cap. It implied that the future value of SoftBank’s assets was lower than their present value, a jarring indictment on their investing ability.

The simplest way to get an idea for how this is done is to use a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model. Of course, sophisticated fundamental investors utilize more complex and nuanced methods of valuation, but clicking through the building of such models gives an idea of the considerations fundamental investors make when assessing whether to make an investment or how it is performing over time relative to their projections. Since these investors operate in sizes that trounce normal trading position sizes, having an idea of when they might start to shift positioning is very useful. Investors are not concerned with impacting the market to the scale of a couple percentage points, of course — their time horizon is much longer and the projected return compounds over time to many multiples of that — but obviously they’re not execution insensitive. What we’re concerned about is what will drive them to adjust their positioning and drive immediacy of market impact.

As stated earlier, valuation is driven by snapshots over time. Good examples of this are Phase 3 announcements, significant company news and filings, and of course, earnings. These serve as catalysts — drivers of reassessment and action. The trader is to volatility as a moth is to a flame. We can expect size and price movement to converge around known catalysts. As traders, in between whatever speculation we’re doing in between, we want to scoop up liquidity on entry and sell it back when it’s in demand. We want to ride the impact of less price-sensitive participants. We also know that without size coming in to help us, some trades might have their expectancy significantly affected.

Take, for example, META, a stock that’s been absolutely crushed relative to its peers this year.

Certainly, the company is not going anywhere, and a trade with the thesis of simple reversion back to its usual market beta was definitely a common one. And if you did try that, you’ve been blown out basically all year. What gives?

Prices don’t drop due to sellers “overwhelming” buyers, but rather due to lack of bid. If you are long, you can’t make a return unless bidding is strong. In META’s case, all the big investors who would normally come in and support the price and add to their investment aren’t because of the uncertainty of future cash flows and the unknown return on the cash Zuckerberg is currently lighting on fire to produce the metaverse. They have no certainty in their models, so they won’t bid. (Worth noting is that the voting structure of FB shares at time of IPO directly resulted in this, as any other company without a similar structure would have had an activist buy a stake so they can transform management. This is a solid long thesis if you are expecting such an investor to come in, and why Elliott Management gets such a strong halo effect on companies it shows interest in investing in.)

Predicting how investors will react and position to catalysts like earnings is some of what makes up event-based trading. We still want to utilize our core tools of assessing expectancy and managing risk, but where we assess the likelihood of which direction the price will move and the magnitude of it in reaction to the event. Useful indicators of the market expectation are implied moves based on the pricing of the options’ volatility, or, in the case of a merger trade, the implied floating probability of the takeover failing as represented by the current price, calculated by taking (merger price — current price) / (merger price — pre-offer price). Trading earnings is inherently unpredictable — even on a “beat”, market reaction can be negative due to lowered “guidance”, and even when that’s good, sometimes everything just sells because why not. Our only real tool, outside of hacking hundreds of thousands of earnings releases and insider trading on them, is to look at past earnings results and company history and make an assessment whether the move will be outsized or muted. But think back to META — even if we don’t trade the earnings, if investors don’t see what they want, the bid might not come back for a while, which could skew the expectancy of longs for a long, long time.