What's the Deal with Zero Days?

Malt Liquidity 70

I’m a trader, I keep my options open

If you’re a reader that has talked to me over the past few years, you probably remember that I have an affinity for near-expiry options, particularly zero-day SPX options. Zero-day trading is a good way to short-circuit your adrenaline — it’s a gladiator’s arena consisting of a thin book built in a high volatility environment where your options’ delta and gamma go haywire while theta decay sucks the blood out of whatever life they have left. I primarily used zero-days to amplify my returns on a move I was expecting by capturing the gamma-ramp along with the delta realized as an option went from out-of-the-money to in-the-money. My strategies were developed in the low volatility environment of pre-2020 markets, where the moves would generally be so slight intraday that you simply couldn’t capture any meaningful returns on delta one strategies. Back then, these options weren’t heavily traded — options in general weren’t realizing that much volume. Of course, this didn’t remain true as we reached 2020. But let’s step back for a moment.

It’s useful at a high level to think about who is trading options in general — you don’t want to trade against the size, so you want to have an idea of what “size” means in a nonlinear market and what the goals of the participants who make up “size” are. I like to think in terms of four categories of options traders: protectors, hedgers, speculators, and liquidity providers. (Note that traders of each category are not rigidly bound to it — participants obviously utilize different or combined strategies within each category to some degree.) Protectors are a group of traders who utilize options for their “intended” purpose — insurance. I picture them as holding very large equity positions that they cannot liquidate easily due to some combination of investment prospectus or potential market impact. They are mostly concerned with delta hedging and portfolio risk and are primarily buyers, soaking up blocks of options across many strikes and expiries to protect against adverse price action. Hedgers differ from protectors in that, while protectors are definitely “hedging”, hedgers’ utilization of options is concerned with nonlinear movement. They could run strategies related to the volatility of price movement, the sensitivity of the option’s relationship with price movement, or even the fluctuations of the nature of volatility itself, among others. Their exposure tends to not be directly to price, and it’s hard to know whether they are net buyers or sellers as the strategies vary tremendously. All we know is that they are transacting.

Speculators are probably the category you’re most familiar with — retail traders mostly fall here. Speculators mostly trade directionally and value leverage and the potential of exponential returns. Their main exposure is generally price and volatility, and they tend to be net buyers, though the strategies used might include selling options against stock or other purchased options (think directional spreads or condors.) Liquidity providers have been discussed a fair bit as well — their role is to facilitate transactions between buyers and sellers and collect the spread. These traders are mostly market makers, and might incorporate some strategies from both hedgers and speculators to reduce their exposure to the risks that arise when collecting spreads in less liquid, nonlinear products. Ideally, they’d be at net zero between buying and selling — every transaction would be paired off and the result would be no position and a lot of pennies picked up through the spread — but practically speaking, this isn’t really possible, and they might carry an inventory of options across books where the flow resulted in them being net buyers or sellers.

So what is “size”? Size in options markets differs slightly from how we’ve thought about it previously. Size in equities markets reveals itself through its market impact as a result of its consumption of liquidity — in effect, a large buyer or seller who you want to get out of the way of. (If you want to buy $100k of a stock and you know someone is selling $1 billion, why would you want to buy the first $100k sold instead of the last?) Note that the goal of size is to not reveal itself so as to minimize market impact. Size in options markets is also revealed by its demand for liquidity that exceeds what the books provide, but it doesn’t have the same price impact that delta one products do. It’s impossible to ascertain the purpose of a buyer or seller of options just by the fact that they’ve transacted. As such, you don’t necessarily have to get out of the way of these traders. Remember that every order made provides liquidity and every order filled takes it.

Imagine a scenario where a protector wants to buy puts that aren’t particularly liquid on a certain stock. Of course, institutional market participants are (usually) savvy enough to disguise their size by varying their orders, but let’s say that you reliably notice the spread being crossed to fill these puts when they become available. Now let’s say that you’re a speculator who wants to take a directional position on the same stock. The protector’s outlook has a different purpose, has a different time horizon, and probably varies in net exposure desired. It might be in your interest to leave an order open to get an advantageous fill to build a position with the exposure you want to accrue. You’ve transacted with the size, but you’re not trading directly against it in a zero-sum fashion.

Now imagine a scenario where you’re a hedger trying to leg into some multi-pronged options position. You notice that the bid-ask spread is wide, and while you would like to transact, your demand for liquidity is not so high that you need to cross the spread. Instead, you walk the book down and place an order to sell one level below the visible ask, but above the midpoint price. To your surprise, your order gets filled. What gives? The visible bid-ask spread is “screen” liquidity. If the spread is sufficiently tight — say, a penny wide on AAPL — it’s hard to undercut. However, in wider spreads, there may be parties willing to transact at prices better than the visible bid-ask, but who don’t want to show their willingness by placing a visible order in the book, perhaps due to not wanting to reveal a position in the market or to avoid the risk of getting picked off and ending up with undesired exposure. This is “below screen” liquidity. Imagine that, while you are walking the book down, a liquidity provider sees your order. They see that due to the prior activity in the book, they’re net short that option, and while their exposure is hedged, they’d ideally like to hold nothing at all. Seeing that the book for their hedge is sufficiently liquid and a closing transaction can be paired off, they meet your ask, giving up a bit of the spread for the purpose of maintaining their inventory. The diversity of participants and the nonlinearity of options allows for the nature of transactions to be much less head-to-head than its equity counterparts.

24 Hours to Live

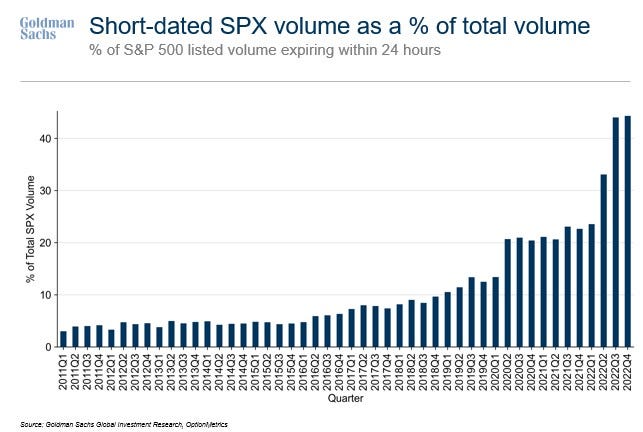

What does this have to do with zero-days, you might ask? Well, the volume in them has exploded:

…JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategists… studied public trading data and found that small-fry investors can’t be responsible for the explosion of S&P 500 contracts that mature within 24 hours, a category known as zero day to expiry, or 0DTE.

By the team’s estimate, about 5.6% of all volume in such short-dated options in the past month can be attributed to retail market orders. While that’s higher than the average for all the index’s options trading, it’s obviously not the dominant flow.

During the third quarter, S&P 500 options expiring within one day accounted for more than 40% of total volume, almost doubling from six months ago, according to data compiled by Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

Whatever the reason, these contracts have seen holders go in and out in a flash. Only about 6% of these options were kept open until maturity, JPMorgan data show.

So what’s going on? It’s hard to really know, of course. But let’s try and put it in the framework we developed in the previous section. First of all, we can probably eliminate protectors from the discussion. Zero-days don’t really fit their objectives in any way, and I can’t see these players turning into degen tourists. However, I think it is fairly rational to conclude that hedgers and even liquidity providers are turning into speculators to some degree. The volume has to come from somewhere, and it’s definitely not primarily from retail. But why?

The relationship between VIX and SPY has remained mostly normal over the course of the year — in general, they are inversely correlated, though a “melt-up” can cause a spike in VIX along with a rise in SPY. However, note the extreme swings in VIX after rallies peaked in Q2, Q3, and Q4 and how it corresponds to the zero-day volume from the chart shown above. I think the change in trading patterns is a result of relatively low market depth along with a high frequency of sizable intraday reversals:

Specifically, I think the behavior of liquidity providers in the underlying markets has impacted how these participants are transacting options. Logically, spread tightness and volatility are inversely correlated — when volatility is low, spreads are very tight, and when it’s high, they widen. Coming in on a spread when volatility is spiking is very risky — the natural inclination is to pull quotes to reduce the risk of getting hit on orders that leave you with exposure that you don’t want. As seen in the chart above, significant intraday reversals — indicating significant shifts in volatility intraday — are occurring at a higher rate than usual. As the year’s gone on, liquidity providers have probably modified their strategies to some degree to account for this regime and adjusted their quoting behavior. Anecdotally, a lot of these reversals have seemed to come on Fed days — my slang for when statements, minutes, or rate adjustments are released from the Federal Reserve. Fed days are categorized by very low trading volume until the events or statements occur, upon which prices whipsaw around on a thin book until the market picks a direction and the quotes come in.

First, let’s think about the hedgers and speculators. Hedgers undoubtedly have some exposure to the behavior of the volatility of the market. If you’re preparing for some sort of volatility event that shifts the market trend, wouldn’t it make sense to build some short term position to reduce the perturbation of your exposure, if not outright speculate on the vol changes themselves? If you’re a speculator, intraday reversals of high magnitude relative to the overall implied volatility of the market provide some of the most ludicrous opportunities to make an exponential profit. Imagine a game where you flip a coin on direction and can at most lose 100% — the premium you paid to play the game — but could easily net 300%+ if you guess correctly. Isn’t the expectancy fantastic? If you have a sense of timing when this game could arise, why not take a moderate punt on a put, call or straddle? You’d also be drawn to the zero-day, as you want as little caked in to the option that isn’t necessary. Give me returns or give me death.

Now let’s think about the liquidity providers. Liquidity providers are quoting across the market, not just on the ES/SPX complex. On large macro days, not only is the index thin, but single stocks are thin as well. After the volume picks up, it is likely that single stocks follow the market through trends and reversals. If you’ve picked up on a pattern of intraday movements that may adversely affect your ability to quote across the market, what do you do? Well, you can accumulate option exposure to pre-hedge or even speculate on the spike that is likely to come. Zero-days are obviously the instrument of choice — why would you pay for theta that you don’t need when you’re focused on intraday movement? Furthermore, as a liquidity provider, you’re aware of the general activity and open interest in a specific instrument — given that hedgers and speculators are also presumably accumulating their own exposure across strikes, you can expect to be able to get off a certain volume.

Here’s how I think it all comes together. Hedgers and speculators picked up over time that these intraday reversals and vol spikes are becoming more common. They use near-expiry and zero-day options to build exposure to when these events might be likelier to occur (low VIX, signs of a rally tapering off, etc.) These trades are lucrative enough that they’re able to punt on multiple occasions — the risk-reward of timing the spike right is too good. Liquidity providers also picked up over time that the intraday reversals and vol spikes are becoming more common. They pick up the signs of increased OI and volume on near-expiry and zero-day options and notice their market making activities on these strikes uptick. They accumulate their own exposure and prepare to adjust quoting accordingly. Since so many participants have exposed themselves in anticipation of a vol spike, it’s almost incentivized to not take the risk of tightening spreads on the underlying prematurely as a liquidity provider or provide liquidity by placing open orders, no matter the participant. Speculators and hedgers benefit from the abnormal movement if they happen to position right, and liquidity providers benefit by selectively quoting and collecting wide spreads as they facilitate the mad dash of flow to exit at a profit and potentially cash in on their positioning themselves. Of course, not everyone can win. Delta one sizing still trounces option sizing and incoming flow in the underlying can reduce all these plans to naught and blow trades out. But clearly some edge was discovered in the option markets, and more and more participants are starting to play.

Is this healthy? I’m not really sure. Certainly, liquidity provision seems to be more prevalent when it’s convenient rather than to facilitate price discovery. I don’t think it’s necessarily bad because there are a lot of fail-safes like circuit breakers and trading halts to prevent things from getting out of hand. At the same time, weird trading edges that arise out of volatility like this are a symptom of the “illusion of liquidity” that the universe of expanding ETPs and publicly-traded derivatives give us. “Real” participants seem to be concentrating their trading volume in certain products while more and more passive flow is distributed across more and more products. Is there sufficient liquidity in all the products tied to increasingly erratic index volatility to prevent wacky non-flow price impact? I guess it remains to be seen.