Liquidity is Everything

There comes a point in every seasoned red-button/green-button pushing practitioner’s life where they lean back in their seat, pause, and wonder how the smorgasbord of rules, regulations, and structured products that makes up our behemoth of a financial system ended up this way.

However, when boiled down to its simplest elements, the system is essentially made up of three pillars: equity, currency, and debt. Equity provides liquidity to hope. Currency provides liquidity to bargaining — our transactions have to be denominated in something. The most important pillar, and what underpins it all, is debt, which provides liquidity to trust. The systems of law and government provide a safeguard of enforcement to trust, but trust without liquidity cannot scale — there is no society without it.1 Connecting these pillars is the banking system, which facilitates the liquidity provision. On top of these pillars, a dazzling array of methods to quantify and transfer risk have been built, but without sufficiently liquid pillars2 , as we were all made aware of in 2008, the entire system can implode.

The simplest form debt takes is “I-owe-you”, the precursor to a loan. Imagine a community where everyone knows everyone else. In this community, if person A borrows a hammer from person B, it’s unlikely that this transaction requires liquidity provision — personal knowledge of the borrower’s creditworthiness is probably sufficient to decide whether person A is going to return the hammer. Maybe person B knows that person A is a nice fellow and is likely to show his gratitude in some manner, and decides that he doesn’t need any explicit promise of repayment or compensation. As this community attempts to scale, personal attestations of creditworthiness becomes less and less reliable. Perhaps person B trusts person A when he vouches for the creditworthiness of person C, whom B does not know, but the signs of illiquidity start to show. Trust’s liquidity is inversely correlated with degrees of separation to an exponential degree. A better system is needed.

Every instance of borrowing has some degree of counterparty risk. I still regret miscalculating my net exposure to the risk that my childhood friend would borrow my Dark Magician card and move away before he remembered to return it. The liquidity of debt relies not only on the ease of transferral to the borrower and remittance to the creditor but also on the ease of recourse in case payment falters. If the only way to encourage a borrower who is reluctant to repay their debt was to chase them down and break their kneecaps, you’d probably have to go look for a loan from a glorified crew. The robust, ever-increasing system of laws and regulations aims to provide as fair and efficient of a system of recourse as possible. Fluidity is to systems of law as liquidity is to finance. Reliable recourse allows creditworthiness to be priced, assessed, and transferred in real time, as we looked at regarding Coinbase a few days ago. In the event of a terminal default, there are tried and true systems to recoup as much as possible to repay creditors. A total absence of ability to repay creditors is thus more indicative of criminal activity or a complete miscalculation of credit risk rather than a failure of the system.

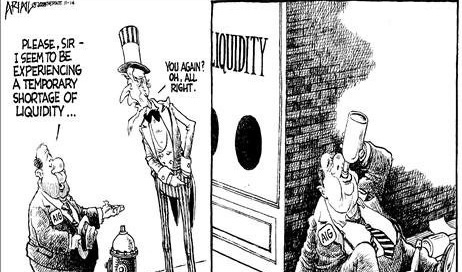

The pinnacle of society’s accomplishments in financialization, to me, is reflected by the risk-free rate, which we discussed briefly a few days ago. The fact that an instrument of debt can maintain such a deep market and have such an infinitesimal probability of default3 to the point that it’s considered a zero-risk investment and is fundamentally used to assess the relative risk of other investments is astounding. While the scale of the system is awe-inspiring in some senses, it also conveys a sense of purposelessness. The mantra of “too big to fail” summarizes an intuition that doesn’t require financial literacy to understand — the system has become so large that it’s irrelevant whether or not an individual actually believes in it. There is a palpable powerlessness of an individual to genuinely attempt to exercise control over the system — instead, all one can do is hope that the people who do control the levers don’t mess up. Belief in systems can be rooted in rational thought so long as the system is constructed logically, as mathematics and legal methodology attempt to do. The belief that a set of humans will take the right course of action consistently is more along the lines of faith. It’s impossible for a group of individuals of any size to keep track of the scale of the interconnectedness in the system. Now that the world is moving away from zero interest rates and finally weaning itself off of financial heroin, the system is showing some track marks, and might not be as liquid as it seems:

Gangwon, a sparsely populated, mountainous region east of Seoul, had tried since 2010 to build a Legoland near the resort town of Chuncheon. After years of delay… the theme park finally opened on May 5.

To construct Legoland Korea, the Gangwon provincial government established a special purpose entity called Gangwon Jungdo Development Corp. (GJC), owned 44 percent by the province and 22.5 percent by Merlin Entertainments, the British company that owns the rights to Legoland. To fund the construction, GJC, through a subsidiary, issued bonds worth 205 billion won (about $150 million). The bonds were backed by the GJC-owned real estate for the theme park and its surrounding area, as well as a guarantee from the Gangwon provincial government, then led by liberal Gov. Choi Moon-soon. Korea Investors Service, the South Korean affiliate of Moody’s, gave the GJC bonds an A1 rating, the highest rating available for corporate bonds.

The proliferation of bond rating agencies highlights precisely how complex and large the system has become. The entities raising debt are extremely vast and diversified and the sums they look to raise are gargantuan, which led to the creation of massive corporations4 whose primary function is simply rating credit. Of course, they only produce the ratings — the number of people who fuel the speculation and machinations of the players who actually supply the capital dwarfs the headcount of these firms.

Legoland Korea struggled out of the gate, too far from Seoul and too expensive for what was on offer, and it did not generate enough revenue to honor the bonds. Also, as South Korea’s real estate market softened, the value of the real estate backing the bonds began falling below the amount of the debt. As the first due date for the bonds was approaching on Sept. 29, GJC was in talks to extend the deadline with BNK Securities, the underwriter for the bonds. Negotiating for such an extension is a tense affair but a relatively common one. GJC was close to buying itself a three- or four-month reprieve, by prepaying BNK four months’ worth of interest that it would additionally owe by extending the due date.

…on Sept. 28, Gangwon’s newly elected conservative governor, Kim Jin-tae, announced that he would not honor the government’s guarantee. Instead, GJC would enter into bankruptcy, meaning that creditors would receive pennies on the dollar. BNK Securities declared a default on the GJC bonds and sought assurances that Gangwon would pay back the 205 billion won, but the government gave only a vague promise that it would honor the guarantee without giving a specific date. By mid-October, the GJC bonds were downgraded to junk status.

On the surface, this looks like a standard, incorrect assessment of credit risk. But what’s important to note is that this bond crisis was caused by an unpredictable action of an individual who happened to gain access to the lever. In a sense, this is unquantifiable — a system’s weakest point is usually its human element. Again, it shows signs of a system that is beyond control, and relies on an element of faith that an elected official won’t completely blow it all up. You might wonder why I even brought this up, given that $150 million is a drop in the bucket for a developed nation with a debt to GDP of nearly 50%. However, think back to the discussion of contagion from a couple days ago — if one set of government bonds goes from the highest credit rating to junk status, why wouldn’t the rest follow? The illusion of a relatively risk-free rate gets shattered, and people start to clamor for their money. Trust’s liquidity becomes strained.

Kim’s move, however, has shattered trust in government bonds. In the South Korean bond market, a local government guarantee was previously enough to ensure a bond got the highest rating, approaching the safety of South Korea’s national government bond. By withdrawing Gangwon’s guarantee, Kim demonstrated that a local government’s guarantee could evaporate for a purely political reason…

Immediately, South Korea’s local government projects ground to a halt. As Gangwon did, South Korea’s local governments issue bonds with their guarantees attached to them in order to build infrastructure, public housing, and other large-scale projects. But Gangwon’s default made those guarantees worthless overnight. On Oct. 27, reports emerged that Incheon Housing and City Development Corp., a publicly owned company responsible for urban renewal for South Korea’s third-largest city, had abandoned a plan to issue bonds for affordable housing construction, as it expected no buyers. Out of the 60 billion won (about $44 million) worth of bonds issued by Gwacheon Urban Corp. (GUC) for public housing construction in a wealthy suburb of Seoul, 40 billion won in debt could not find a buyer—the first time in history that GUC failed to sell out its bonds.

There are many theories on what would cause a financial apocalypse. Some theories, like the one where the stock market becomes too passively invested in ETFs and the liquidity in the underlying evaporates which leads to a catastrophic selloff when an event induces a rush for exit liquidity, are somewhat plausible. Others, like the one where the “mother of all short squeezes” finally happens on Gamestop and takes out the central banks (and of course, Citadel), are less so. Personally, on the rare occasion that I have a nightmare, it takes the form of the risk-free rate no longer being anywhere close to risk-free, throwing financial valuation and risk models into utter chaos and destroying price discovery. And, in a sense, a small scale version of this happened:

Corporate bonds are considered less safe than local government bonds. If few buyers are brave enough to buy local government bonds under these conditions, even fewer buyers can muster enough courage to buy corporate bonds. One of the safest corporate bonds in South Korea is issued by Korea Electric Power Corp. (KEPCO). The returns for KEPCO’s three-year bond had climbed from 2.184 percent to 5.825 percent since the beginning of this year. But in its latest issuance, the KEPCO three-year bond worth 200 billion won (about $146 million) could not find a buyer.

Domestic trouble has led to international trouble. On Nov. 1, South Korea’s Heungkuk Life Insurance Co. declined to exercise the call option on its dollar-denominated bonds worth $500 million… The last time a similar non-call occurred was in 2009, in the wake of the global financial crisis. The non-call crashed the value of Heungkuk Life’s bonds, as it signaled to the market that the company could not come up with the money to buy back the bonds. Worse, Heungkuk Life’s non-call dragged down the value of other bonds issued by South Korean companies generally—and even bonds issued by other large Asian companies such as AIA Group and the Bank of East Asia in Hong Kong… Heungkuk Life abruptly made a 180-degree turn and said it would borrow money to exercise the call option after all, reportedly under heavy pressure from South Korea’s financial regulators.

No empire lasts forever. At some point, dollar hegemony will come to an end, as will the reputation of US Treasuries as the ultimate safe haven investment. I wonder what form the next iteration of the debt system will take. By being part of a society, on some level, every system that is built will have some element of humanity and trust to it. No matter how much logic and functionality is abstracted away into, say, a codebase, humans still have to maintain it, at least for the foreseeable future. And unless we succumb to future AI overlords, I’d imagine that we’ll still have humans overseeing something, unless a Tether explosion ends humanity. In the future, though, hopefully after I’ve extracted all the value out of my USD that I can, I do expect a system to emerge that doesn’t require humans to have to move the levers themselves, where debt is automatically repaid as long as the right coffers are filled, and payments aren’t subject to the whimsy of a human who happens to find themselves in power. Perhaps that system won’t revolve around a centralized source of liquidity at all! Who knows.

To me, philosophically, this is why the Fed cares about bond market liquidity more than anything else

Ironically, the more liquid these pillars are, the stronger they are

Of course, this probability is somewhat influenced by the power of a government to print its own currency

Moody’s and S&P, the two largest credit rating institutions, both employ tens of thousands of people