Just in time for the fall semester of 2021 to start, student loan debt once again comes into vogue as desperate politicians realize that the very predictable consequences of infinite liquidity are decimating the risk tolerance of small businesses and restaurants in cities. Alas, I digress.

A favorite axiom of mine to repeat is that “artificially subsidized cost of capital causes serious risk transferral externalities”, and I have previously written on how this has caused the ZIRP-flation of the economy. However, by far the most egregious offender of this outside of markets is the federal college loan system, a massive corporate labor training subsidy shrouded in the Trojan horse that is good politics.

Inflated Worries

First of all, let’s clarify something about inflation. Inflation is a systemic problem sold to individuals as their own. As long as the individual does not continue to take out debt as the rate of inflation increases, they will benefit from it even if their salary lags, due to their debt accruing at the already-issued rate which is not adjusting for inflation. Individuals also benefit because institutions have to outpace the rate of inflation as the cost is so massive to them - they have to allocate assets to anything that can potentially return more. Thus institutional liquidity is provided to a lot of speculative assets, which a) drives the price up (TINA market theory) and b) provides an opportunity to get out. There is no such thing as an “inflation hedge” - there is only outpacing the rate of it. Think about the mentality of your average American who owns a home who is told that a) it is a form of retirement equity and b) who does not understand that it is a rates product leveraged against 30 years of forward earnings. Inflation is great for people who are overleveraged, as most Americans implicitly are against their houses, as long as they do not continue to leverage themselves at inflated rates. 2% in a year is meaningless to the individual whose paper net worth is increasing at a much higher rate given the effects of liquidity runs on housing and large cap liquidity, but it induces investment from large players to outpace it. If I have 10 billion dollars, the difference between 2-4% is huge - if I have 1 million dollars, the difference between a 2% loss and a 4% ‘loss’ to inflation means that I have to stay at a Radisson instead of the Four Seasons on my next vacation. Inflation incentivizes investment while it subsidizes the cost of already issued debt to the individual. Of course, when this trickles down to real goods, there is a mismatch in liquidity between immediate and necessary purchasing power and paper net worth, but this follows the axiom - it’s an externality of the cost of capital being subsidized so deeply elsewhere that real goods are bid up, not solely due to ‘inflation’ itself.

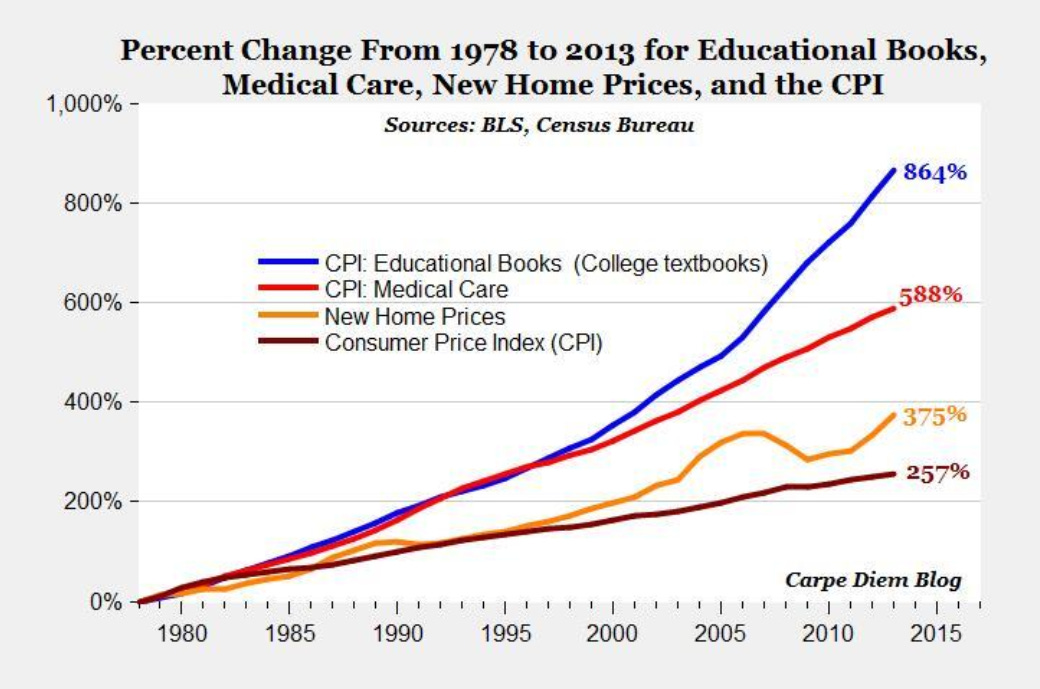

That being said, let’s check out the price of college textbooks.

What happened in the early 2000s?

Well, federal loans are not dischargeable through bankruptcy, and the federal government is the only entity that has the power to enforce garnishing of wages - but private loans became disincentivized because they also became undischargeable through bankruptcy. Given the huge subsidization of the rates of federal loans versus private loans, without the ability to declare bankruptcy, it was natural what would happen - people choose the up-front cost of federal debt because it was brain-dead obvious to do so: you have a loan that doesn’t accrue interest until you theoretically have finished college, and it’s a supremely below market rate, especially in a zero rates environment. A margin loan through a credit card that’s uncollateralized runs you about 20%, but an uncollateralized loan for a diploma with no guarantee of future earnings only runs you 5%? The risk has to transfer somewhere. In exchange for this massively subsidized loan, you lose the ability to ever get a clean slate, and the real effects of this Faustian bargain have been documented profusely by actual investigative journalists.

So instead, let’s think about the risk.

The individual, obviously knowing the horror stories, gets a subsidized market rate in exchange for potentially permanent debtorship if they don’t finish. However, one needs a degree to get a job in the credentialism economy. Thus the cost of subsidization is transferred to the individual in a potentially lifelong contract while any old big company can essentially require you take this risk to even be qualified for the job. Government education subsidies result in the cost of training employees for companies to be massively subsidized, as that is what most business or finance degrees are - job training to perform roles that aren’t really specialized, where most of the learning comes from on-the-job experience where the only prereqs are a moderate understanding of arithmetic and the “Microsoft Office Suite” (god, this is the “words-per-minute on the resume” of the 21st century) and a work ethic. And what happens when there is an infinite liquidity provider (because Federal loans are essentially unlimited issue and tied to the cost of going to college itself)? Regulatory capture becomes a business model - capturing any slice of that infinite liquidity - because that credential has become entrenched in every facet of modern society. Could anyone get past an entry level online job application auto-filter without having a degree on their resume? I don’t think so. As such, colleges charge more and more tuition for no reason, as the pandemic nakedly revealed - stuck inside for a year? no refunds - and the cost of goods required for classes hyper-inflates. This is the bad kind of inflation - there is no subsidy for future investment, it is simply regulatory capture driving up the cost of the goods any college kid is coerced into buying with their loans.

I’m well aware of this. How do we un-fuck this?

Good politics is bad finance, and good financialization is bad politics. And, I dunno. I think we can take a crack at this, because I’m bad at playing politics.

First, we make college endowments securitized relative to the loans they can make against US Treasuries. Treasuries provide the liquidity subsidy to the colleges to independently offer loans to every student that accepts admission - no longer is it a federally run system. College endowment offices then act as a prime brokerage of sorts (let’s be honest, the large ones are all equipped like hedge funds anyway - they’re overqualified to do this) to their students. Each college issues its own loans against its federal liquidity scaled in some way to their endowment. Simple incentives can apply - the more rich kids, foreign kids, or legacy kids that are admitted, the less government liquidity subsidy you get. The more speculative loans you give out to people who need financial aid, the more the government will subsidize your liquidity. Diplomas can be withdrawn if payment is not received after a certain amount of time after graduation - a credentialism default swap, if you will. This way tuition cannot inflate against government loans directly, as the loan is bookmarked against the university itself - they are bound to precisely how much tax-protected money they have in their coffers. For state schools, their liquidity subsidies can be managed by state governments and subsidized in part through bond issues from voters. Make voters pay for the education subsidies they think are necessary for society in any small way - make it their debt that they are owed in some small part that might be forgiven. After all, it is “University of California”, “City University of New York”, etc.

Each major and family net worth bucket (because raw yearly salary is misleading) has its own “margin maintenance cost”, much like a client of a prime broker has their credit with the bank fluctuate based on PnL. They should all essentially “pay” the same amount, just the margin requirement would be different - ultra high net worth individuals would have a near 100% maintenance margin, thus making their tuition an up-front cost and not allowing them cheap leverage off of non-interest accruing federal loans they don’t need, and individuals from less privileged backgrounds will have much lower maintenance margins. Individuals who need liquidity to get by for day to day living can apply for essentially a modified food stamp program with some spending money (because you’re in college - live a little!), preventing regulatory capture from textbook companies, “online homework code” companies, etc. Based on family net worth, you can have a lower maintenance margin for lower net worth families and a slightly higher interest rate with a delayed payment plan. It can all be structured with the college itself. This incentivizes colleges to not take too many students for each major (so they can balance out their risk profile, as major prospects are obviously not created equally - value vs growth, anyone?), but it also self-selects for the kids who are hungriest to try and make it in a speculative major that is more esoteric than transactional. The cost of the risk is a bit higher, but they can always declare bankruptcy. Each semester enrolled and started adds one semester’s worth of cost to the total loan amount, thus the margin maintenance increases predictably over time. This would also make it easier to take semesters off - you are still paying interest, just the sum total is only for the semesters you completed.

You know where I’m going with this, don’t you?

On top of the college loans, to fund their margin maintenance, students can sell equity in their future earnings up to a limit. You can already do this with prospective athletes, as I’ve noted before. Why not students? Equity is not debt - you don’t owe anyone if the equity you issue is worthless. Some might find it macabre to speculate on the futures of fresh grads, but I think it’s a benefit to society to outsource the full brunt of speculation from the 18 year old taking the student loan to professionals and degenerates alike. Isn’t it kind of wholesome to root for someone’s success while you have a stake in it?

Potential effects

The brilliant part of this proposal is that it reduces demand for college degrees, both individually and institutionally. Private colleges that exist as a function of regulatory capture of tuition will simply fold. Administrative bloat is unprofitable, is a known money suck, and will crumble. It’s not that profitable of a business, and running a college never should be profitable. It’s legitimately pricing the risk to the individual while also not making signing for college debt a lifelong burden if it goes wrong.

Big companies will adapt. With less demand for four year degrees, it will become less of a mandatory qualification to have one. You might have more direct trainee programs as a result. This would also make it easier to fulfill diversity quotas. There are a lot more diverse high school grads in a local ecosystem than college grads and it’s not like you need a four year degree to spend some time in a JP Morgan wealth management division in Spokane and understand what’s going on. Include a government incentive to pay slightly more than your average wage, and all of a sudden there is a viable, health-insured alternative to going to college and working your way up. Direct experience is a much more valid predictor of success in a given career than a four year degree is. This method of thinking about student loan debt solves the issue of spiraling student debt in the 20-25% of cases where people cannot get a job/finish their degree, cuts down on indirect corporate handouts and college textbook/tuition runaway inflation, incentivizes corporate training programs, and enables diversity in quality hiring, not quota games. What’s not to love?

Understanding liquidity is simply understanding the friction between theory and reality. While intentions may be good and soundbites must sound nice, the true cost of capital will realize itself somewhere in the system, undoubtedly. If unchecked for too long, it entrenches regulatory capture. Which brings me to my favorite axiom - everything is liquidity.