When the price of a commodity rises, it is usually due to one of a few things: supply decreasing, which increases the bidding premium and leads to spread-crossing, as we saw in meat prices during the pandemic, or demand outstripping supply, either organically - need I post another chart of SIGL or TSLA? - or through artificially limited supply (done through purposeful underproduction relative to true demand, and relying on the demand to produce a ‘pop’, much like a traditional IPO), like Supreme drops or sneaker drops. Conversely, when the price of a commodity drops, it is commonly due to supply gluts: oil is the most notorious example, as it is what led to the cratering of oil prices from $100+/barrel.

However, the lobster is a curious case. It was known to be cheap and plentiful - peasant food - back in the 1800s, and was commonly canned as a cheap source of protein. Through artificial scarcity - while it was plentiful on the coasts and in the ocean, the center of America only had access to it when it was shipped by train, which led fishermen to try and pitch it as a premium product - on top of actually figuring out how to cook lobster ‘properly’ and haute taste buds evolving to encapsulate the freshly-cooked lobster, it became a premium product worldwide. No illusion the Michelin guide could give off, however, can stave off price drops due to supply gluts:

Ever since China blocked imports of Australian lobsters late last year amid a trade spat between the two countries, Australia has been awash in local crustaceans.

There are so many lobsters that authorities raised the limit for how many lobstermen could sell directly to the public at the wharf. Australians far from the coast are getting freshly caught, live lobster for the first time. Chefs are experimenting with new lobster dishes that previously would have been too expensive. And the low prices are convincing amateur cooks to make lobster at home…

Usually, 95% of Australia’s most valuable lobster species, the western rock lobster, is exported. Most go to China, where consumers prize the lobster’s red color and pay top dollar. With the Chinese market off limits, many of the lobsters are being sold domestically for as much as half the price as a year ago

While it is no negative oil, it is pretty amusing to think that an entire country is in Bubba shrimp speech mode, but for lobster. Lucky, the ocean can’t run out of storage capacity… can it?

Stormy Seas Ahead

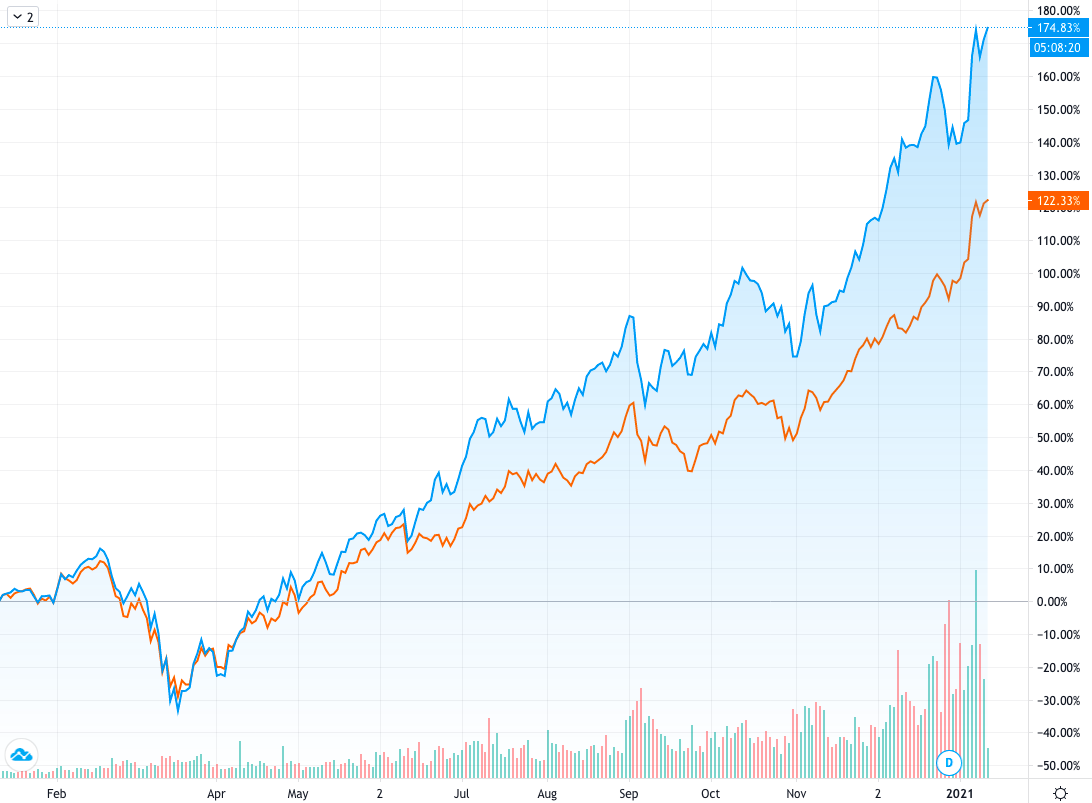

A little while ago, I wrote about the emergence of sketchy OTC products on ARKK, the notorious ETF that is essentially billions of dollars allocated in comparable fashion to the average Robinhood investor’s portfolio. Naturally, given ARKK’s rise this year, shorts are now piling in:

Short interest as a percentage of shares outstanding on the flagship $21 billion ARK Innovation ETF (ticker ARKK) jumped to an all-time high of 1.9% from about 0.3% a month ago, according to data from IHS Markit Ltd. A similar spike can be seen across the Ark Investment Management lineup, with bearish wagers on the $9.4 billion ARK Genomic Revolution ETF (ticker ARKG) and the $5.9 billion ARK Next Generation Internet ETF (ticker ARKW) also near records.

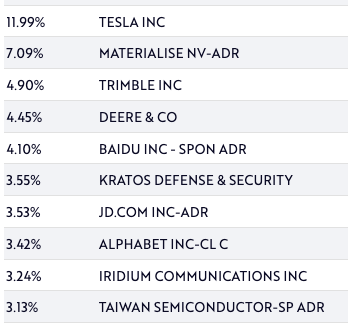

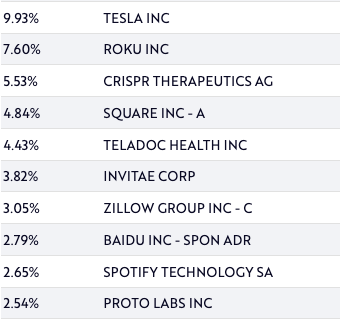

A problem with an ETF that gets really popular is that there is a finite amount of capital you can deploy to your “best” trading ideas. While you could comfortably buy 10 billion worth of AAPL stock, if you are a “tech growth” ETF and have about $20 billion to deploy, there are a very limited number of stocks you could aggregate positions in without lifting bids and pushing the stock up. And as your purchases reinforce your ETF share price increasing, and more money piles in, you have to keep bidding stocks up (and hoping they follow continuously upwards) and so forth. With this much inflow - the net inflow in the past year to ARKK has been roughly 10 billion - you quickly run into the Berkshire problem, where you have so much cash but not enough places to effectively deploy it. Meanwhile, the portfolios that they hold are concurrently becoming more and more overweight the largest components. Take a look at ARKK’s and ARKQ’s holdings:

Pretty similar huh? ARKQ is more heavy weighted TSLA and BIDU, but ARKK holds more memes.

It seems pretty obvious that most of ARK’s ETF inflows are due to marketing of their TSLA exposure as stock picking prowess that, for whatever reason, people insist on paying between .5-.75% in management fees for instead of just direct indexing themselves (as all the holdings are published in their proportions on the website). Thus, you could theoretically short either ARKK, ARKW or ARKQ for direct exposure to TSLA, or even a correlation trade on ARKG (as, well, all their publicity has come through TSLA longs, so potentially an outflow in the TSLA-tied funds would spill over). ARKG ties over with being heavily weighted CRSP, and ARKW is also 10% TSLA and 6% ROKU.

What’s interesting, however, is ARKK has significantly more AUM than the other ETFs, but they all have fairly correlated holdings - particularly TSLA in very similar weights. Not only this, ARKK is much more frequently traded - the options chains on ARKQ are flat out illiquid, with awkward strikes (as retail prefers round, convenient numbers like 100 as opposed to 79.84). So what do we make of all this, having multiple similar ETFs with varying degrees of liquidity?

Recall that the function of liquidity is to facilitate price discovery - it naturally follows that the more liquid ETF will stay in line with its theoretical value more closely than the less liquid ones. But at the end of the trading day, each ETF is rebalanced according to its Net Asset Value. So, if I theoretically wanted to short TSLA, where would it make sense to do it - the stock, which is the most liquid, but has the most spread-insensitive retail traders, or the illiquid ETF, or the middle ground?

I’m not totally sure - but if an asset is illiquid and people will bid it up as it goes up and cross the spread to get in, then it would follow that if the same asset is dropping fast, people will cross the spread faster to get out. So, theoretically, I could short the most illiquid ARK ETF heavily tied to TSLA, and hedge off the other stock positions, and as people sell off their ARK holdings in the case TSLA drops massively, they would pay extra to get out of the position compared to me covering my short in the more liquid stock. The nice part of being able to directly replicate an index or ETF is that, well, you can also inversely trade these products and take advantage of the relative liquidity to gain a bit of extra edge, on top of not paying the management fees.

On that note…