Thanksgiving in May

Let’s revisit two general statements I’ve made regarding inflation

Inflation is a bit of a self fulfilling prophecy, and the only “inflation hedge” is to outpace the rate of inflation through rate of return. This is why owning large cap liquidity or real assets is so valuable until the speculative mania tapers off

and crypto liquidity:

While tokens are built on 'hot air' — there isn't an underlying business involved with cash flow generation/accrual of debt for coins — the fact that there is liquidity is fundamental value. I think of tradable crypto as essentially a put on central bank stability — <1 delta in, say, the U.S., much higher delta in, say, Turkey. Specifically, they are far dated, far otm puts. This would imply that the extrinsic 'value' crypto has (bc there's no intrinsic for these options, obviously) is almost entirely IV (given that they're on the extremes of the volatility smile), and there is no 'exercisability'. As a result, crypto "inflows and outflows" are more akin to rapid bidding/crushing of the implied volatility of an option rather than normal delta one products, which exponentiates the nature of the move when it comes due to the nonlinearity of option movement itself.

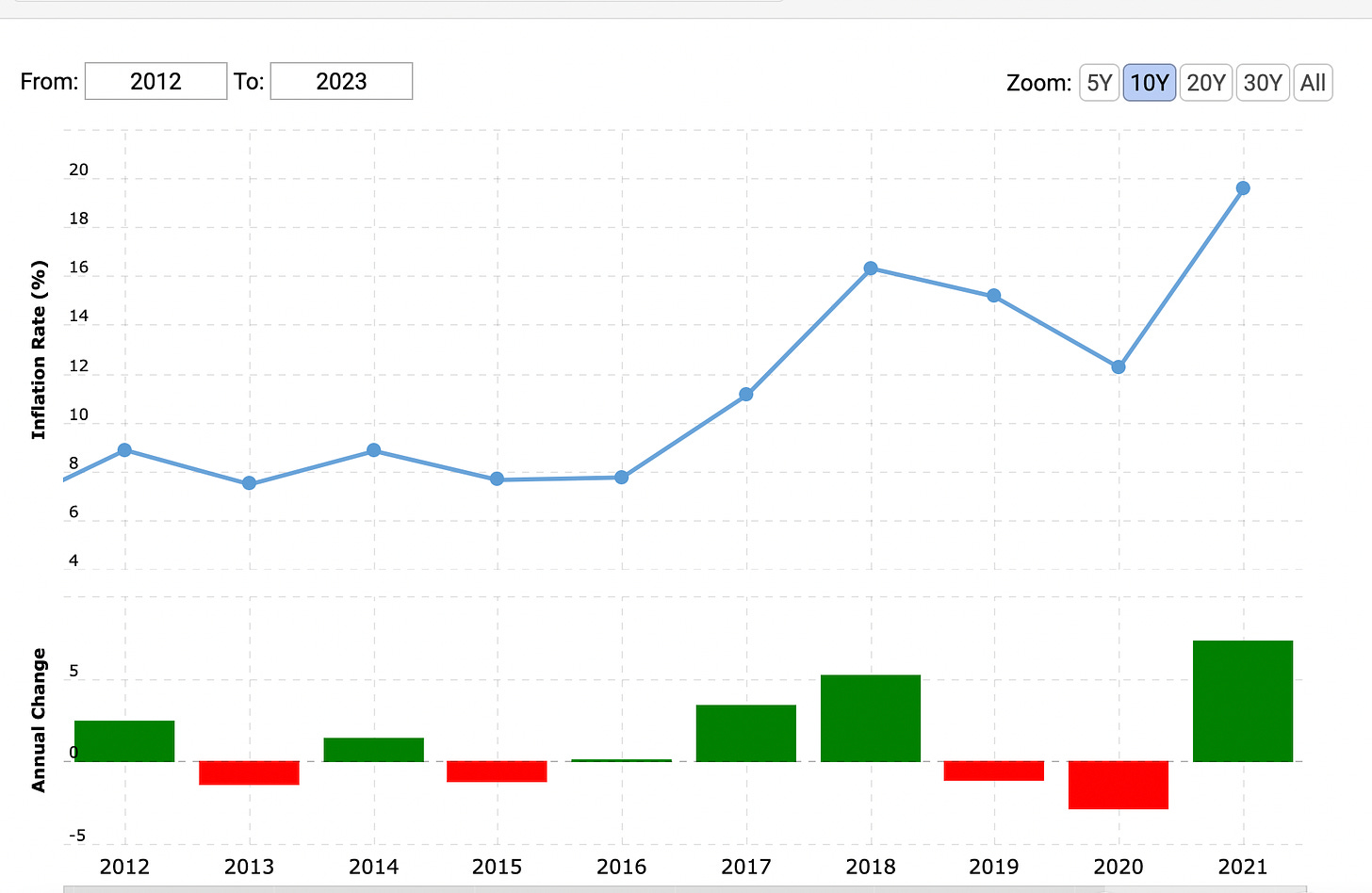

It’s no coincidence that I picked Turkey as my example in this model:

Keep in mind that the simplest way to define inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.” In a central bank regime, the appropriate way to control inflation in an isolated system is to raise interest rates — this incentivizes saving and attempts to slow the velocity of money, easing rapid price increases according to demand and stabilizing the currency by slowing the rate of asset flight.

When we broaden the system to allow interactions between other currencies, foreign assets and countries, a new problem comes into play — that of capital flight. A concept foreign to most Americans is the idea of capital control, to preserve liquidity and demand for a native currency such that all the investable capital doesn’t drift to dollars. With this restriction, there becomes a singular response to high inflation — asset flight in any manner possible. As such, Turkey’s stock market performed ludicrously well in 2022, because if you can’t unbundle from the Lira, you might as well buy anything with the hope of appreciating in line with the currency’s devaluation.

This is all pretty straightforward stuff in line with orthodox thinking about central banking. Enter Erdogan:

Turkey’s central bank cut its key interest rate for a fourth consecutive month on Thursday to single digits, intensifying a monetary policy demanded by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan despite the country’s high inflation rate.

The bank’s monetary policy committee said it cut its benchmark interest rate by 1.5 percentage points to 9%.

Turkey was plunged into a currency crisis last year after the central bank implemented a series of rate cuts at the urging of Mr. Erdogan, who favors lower rates as part of an unorthodox strategy to encourage economic growth. The crisis wiped more than half the value off the lira and pushed millions of Turkish people closer to poverty.

Mr. Erdogan’s government has also said that rate cuts would eventually lead to lower inflation, contrary to what has been observed historically in global economics.

Note that Turkey’s inflation rate at the time of these rate cuts was 85%.

Even ignoring “mainstream” thought, putting together the pieces results in a policy that makes no sense. A low rate naturally disincentivizes leaving cash stagnant in a bank account, meaning that it has to be allocated to some market or asset. Furthermore, when the government issues debt in this environment, it creates massive duration risk for the buyer in the event that interest rates rise — think SVB, where mark-to-market losses due to rising rates created an irreparable hole in their balance sheet (and led to events we’ve discussed before.) So you’re stuck in an environment where, as a normal banking institution, you want cash deposits, you don’t want government bonds, and your clients don’t want either of these things. On top of this, Turkey practices strict capital control:

Erdogan’s government has deployed a range of unconventional measures to stabilise Turkey’s $900bn economy, including tight controls of companies’ transfers of foreign currency and the 2021 launch of special savings accounts to protect depositors from lira fluctuations. These tools have helped slow the lira’s fall, although the currency is still trading near a record low at TL19.67 to the dollar.

How is this ever supposed to temper demand? And how are you going to ensure liquidity for your own debt? Necessarily, such policies will require serious deficit spending to even maintain a budget. This policy strikes me as even more bonkers than what Gerald Ford advocated for in the 1970s:

The new president, Gerald Ford, went before Congress and delivered a speech he hoped would be inspirational. Instead, its key message was resoundingly derided.

Ford’s theme was “Whip Inflation Now.” His theory was that if every American practiced frugality—growing backyard vegetable gardens was one example—inflation would be whipped. His administration asked citizens to wear WIN buttons, as he did, to show their support.

Naturally, telling one of the most consumption-heavy cultures in history to “just stop” is like, I dunno, trying to nuke a hurricane. But what’s particularly amusing is how an American did react:

…Hayes had already won three consensus national championships for the school when Ford made his speech. At the time, Hayes’s annual salary was around $27,000, according to contemporaneous reporting.

That isn’t a typo. Football coaches hadn’t yet discovered they could demand the keys to the universities’ vaults. Even adjusted for inflation, Hayes’s salary was the equivalent of only some $165,000 in 2023 dollars…

But when the university approached Hayes during the 1974 season about a nice raise, he said no.

The reason? Hayes thought Ford’s message had great merit and felt it was his responsibility to help ease inflation by refusing a bigger salary. It seemed downright unpatriotic to take a raise. He was confident that he and his wife, Anne, could get along fine on $27,000.

I mean, wow. I don’t know of a single American who would do this other than the ones who are confused about tax bracketing.

The core problem Erdogan’s policies have created is the same problem that irrational panic selling creates — given the prior of the irrational behavior, all of a sudden a prisoner’s dilemma emerges where the logical option is to act in a manner that perpetuates the problem. Hyperinflation and bank runs are the financial equivalent of manic and depressive — one is runaway consumption, one is runaway conservation. There is no way out unless somehow the population collectively decides to violate the prisoner’s dilemma en masse — (3,3) on a national scale. Unless…

Crypto “solves” this

Unlike gold, which has a physical presence and a delta one spot, crypto is a quasi-option. Unlike gold, circumventing capital controls by accumulating crypto isn’t really visible — a hardware wallet could easily be mistaken for a Juul as opposed to, y’know, trying to smuggle hunks of gold out of the country.

In the short term, asset flight through crypto is perhaps the best circumvention of capital control in the face of real-time runaway inflation. You will come out scathed, but not destitute. Independent of any other consideration, this is a convenient source of alternate liquidity — Bitcoin volatility is relatively reasonable compared to the Lira due to the actual upside present (as a currency in an inflationary environment is inherently negatively skewed without sufficient rate increases.)

It’s not a great option, but it’s better than nothing. Plus it’s probably easier convincing people to take Bitcoin than Lira.

The issue arises, again, due to cooperative behavior. Even after hyperinflation, a country can recover, like Germany did (twice.) But it requires “buying in” to whatever national currency develops in its place. If an alternate source of liquidity usurps the national currency, however, inherently monetary policy will fail — there’s no “central bank” of crypto (or any sort of debt facilitation a la perpetual bonds — this is the main flaw with decentralization as a concept.) If you’re a Turkey resident, you’re stuck between a rock and a hard place if you cannot leave the country financially and physically — you still need to pay your taxes and buy goods, but your financial interests are best served avoiding your national currency. Tethering Turkish goods to crypto would be utterly reckless — after all, a government works to suppress tail outcomes and preserve itself by (supposedly) maintaining stability for its population. Such an action would be a contradiction to the interests of the government itself. It’s natural then that the nation must oppose crypto adoption, and the residents still physically present must buy into the new system. In effect, a central bank that allows runaway inflation is essentially rugging its own population — the person with 3 million in Lira denominated assets suffers complete destruction, while the person with 30k in Lira denominated debt gets an effective reset. Everyone is back to square one.

This is a core flaw of central banking in general — it concurrently requires independence from authoritarian whims, but then the institution itself turns into an authoritarian, unchecked enforcer. At some point, when systems have sufficiently developed, their primary function becomes self-preservation rather than facilitating at-large societal benefits. It’s currently playing out in Turkey, but all central banking is theoretically susceptible to this sort of chaos (as touched upon in my analysis of governments choosing not to honor their own debt.)

Elections have consequences, and if Erdogan’s policies continues, it seems almost certain to continue the rugging of the population. But I’m not so sure his opponent, if elected, would fare any better — he could undo some policies and stem the tides, of course, but that core faith in the system has been irrevocably damaged. And that’s the core flaw of central banking:

Belief in systems can be rooted in rational thought so long as the system is constructed logically, as mathematics and legal methodology attempt to do. The belief that a set of humans will take the right course of action consistently is more along the lines of faith.

Are policies such as inflation targeting, rate adjustments, and BTFP logically sound and checked powers, or are we just trusting a secluded group to take the right course of action?

Food for thought, and more on this later…