As the saying goes,

Any rate the market offers is, by definition, fair.

But it’s surprisingly hard to define what, exactly, a “fair” market is, given that a fair market is not an equal one. While one can slide up and down the supply/demand curve at will in the econ textbook world, in reality, we have trillions of dollars in skyscrapers, data centers, fiber-optic cables, and microwave radio towers to facilitate the fluid functioning of just the lit markets, on top of a battalion of coders and paper pushers to operate fifty levels of fail-safes. What exactly is a “fair stock trade”? Should the best execution win, or should we compensate the best executors to allow tighter spreads on screens?

Being a middleman is by no means riskless. Credit institutions are naturally exposed to counterparty risk on relatively uncollateralized debt — what good is rapidly accruing credit card interest if the borrower has no ability to repay their debt, given that it’s unsecured? — and operational risk, such as identity theft and fraud. To mitigate these risks, they can adjust the lines of credit extended to individuals based on creditworthiness (reducing liquidity offered), block certain transactions unless expressly approved (pulling liquidity entirely), and incentivize more reliable, higher value users to utilize their cards more (payment for order flow.) Similarly, market makers utilize a lot of the same tools to mitigate their risks while facilitating transactions — they may reduce the size and depth of on-screen quotes during more volatile periods (reducing liquidity offered), remove quotes entirely when prices gap around so as to not get adversely hit (pulling liquidity entirely), and incentivize non-informed, reliably profitable retail flow to get routed to them to execute (payment for order flow.) In markets, while the movement and pulling of quotes is regulated by NBBO rules and anti-spoofing measures in Dodd-Frank, payment for order flow has only recently come under close scrutiny, perhaps unjustifiably so.

On a less granular level, what even should be allowed to access capital markets? How lenient or restrictive should we be on which products everyone should be able to buy and sell, as opposed to only “accredited” investors? How much protection does everyone actually deserve? Why are we all here?

So begins the superhero/villain origin story created in response to the Great Depression to answer these existential questions:

…it’s actually quite hard to define what exactly a security is, because the definition (in the US) is intentionally vague so that it can exist as a regulatory catchall. Beyond the actual text of the Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934, let’s think about the motivation: the Great Depression had just occurred, and with it, a calamitous bank run that destroyed a lot of the economy and stretched the financial system to its absolute limits (or collapsed it, depending on how you think about it.) Note that while speculation is the foundation of the financial system, too much of a useful thing is still, in fact, a bad thing. Two principles arise out of these pieces of legislation:

The government wants to prevent false, unrealistic promises that don’t quite amount to fraud from being marketed to investors

The government wants to know what exactly is being offered as an investment

That “government” is the regulatory body we’ve all come to know and not love; the SEC.

The SEC was created with a “three-part mission”

Protect investors

Maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets

Facilitate capital formation

that could realistically cover every single mobilization of liquidity underneath US jurisdiction. I tend to think of the SEC’s three prongs in a different manner: securities registration, securities supervisation, and financial entity compliance. Securities registration answers the “What can trade?” question; examples that I’ve written about include “What is a Security”, “Either/Or — The Ripple Conundrum”, “The SEC Won’t Let You Be”, SPAC shenanigans, and more. You’ll see a lot about Howey in these posts. Securities supervision tends to cover unethical and criminal behavior, such as fraud and insider trading. You can refer to the FTX series and insider trading commentary for specific incident analysis. Compliance is a bit more tricky, but you can read about bank messaging and prospectus enforcement here.

The point of this diatribe is that the SEC’s job is as much philosophical as it is practical, and is thereby subject to the rationale of who’s in charge. Unlike math, where the statement must provably and logically follow step-by-step from the definitions, the SEC’s role plays out under the constraints of reality, where no matter how theoretically rigid rule-making and enforcement might be, it runs into practical questions and sways the timeline accordingly. For a while, monitoring insider trading simply wasn’t a priority, as noted in this column,

I’m pretty sure a fair chunk of historical hedge fund outperformance that wasn’t pure quant/execution edge involved some inside baseball — insider trading wasn’t really cracked down on until Raj Rajaratnam’s prosecution post-2008, where, curiously,

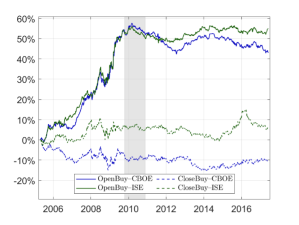

Before Rajaratnam’s arrest in October 2009, the put-call ratio strongly predicted stock returns. In portfolio sorts within the universe of S&P 500 stocks, the portfolio decile with the highest put-call ratio on a given day underperformed the bottom decile by 0.24 percent over the following week, or 12.1 percent per year. Moreover, the put-call ratio was more profitable than any other known stock anomaly when applied to S&P 500 stocks. Strikingly, the return predictability of the put-call ratio abruptly disappeared shortly after Rajaratnam’s arrest and remained absent for the rest of the sample period.

The figure below shows that the prediction ability disappeared almost immediately after the arrest.

and enforcement generally ceased against the biggest players after Preet Bharara started suffering losses from over-zealous pursuits (there isn’t a single group of people more obsessed with their win-loss record than federal prosecutors), though one could also attribute this to the heightened emphasis on quantitative trading rendering proprietary information kind of immaterial.

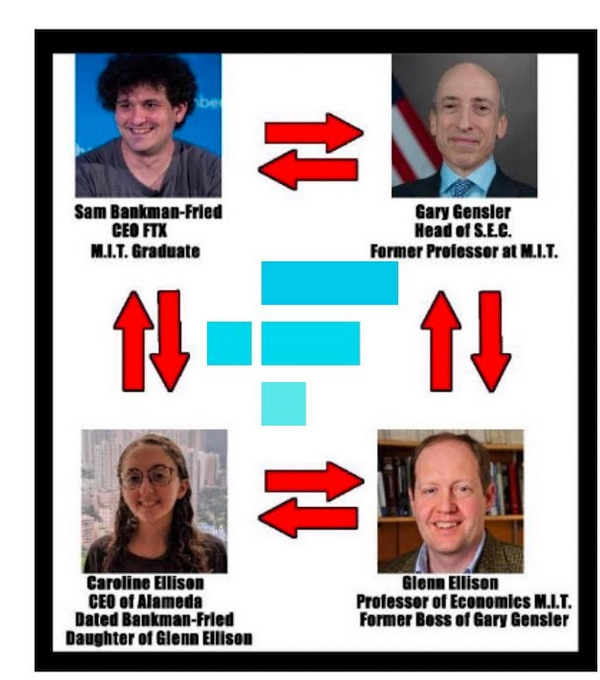

The SEC, in my view, should be a sort of faceless, nameless version of Batman monitoring the dollar-adjacent world from the shadows, its enforcers coming across as the perennial anonymous “FBI agent monitoring the chat”. I can guarantee that even my industry veteran connections would struggle to name more than a couple of SEC chairs — they’re not Presidents or Justices. But virtually every single person who has interacted with any market from 2020 onwards, retail or otherwise, knows the name “Gary Gensler”, who seems to function as a sort of Charlie Brown perpetually missing the football while trying to kick it in an attempt to make a name for himself. And like the heads of many other faceless regulatory agencies, it’s not a good thing when that head becomes commonly known.

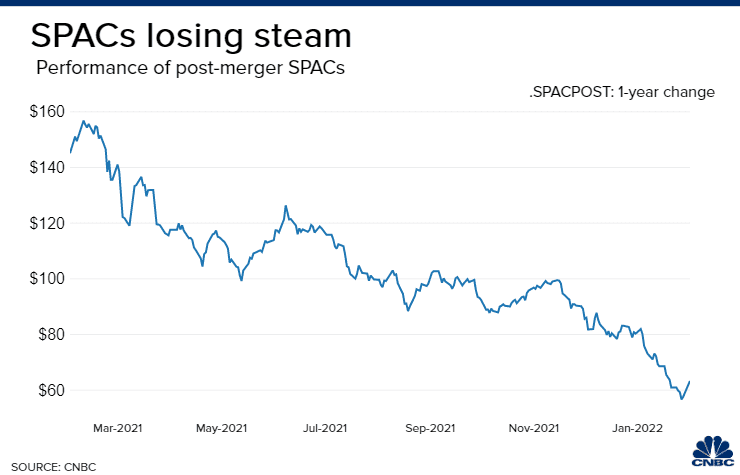

Where to begin? Let’s start with reverse mergers. Ever since Muddy Water Research became a household name, pretty much everyone has known about the loophole of merging with a shell to dodge compliance versus having to file an S-1 (most notably known as what led to the downfall of WeWork). While initially popularized with regards to Chinese listings, this structure quickly became the fuel behind the SPAC boom of 2021. While I’ve generally been laissez-faire on the topic,

Being an American inherently means having an excess of choices and an almost unhealthy enabling of the ability to make those choices, whether it’s purchasing 20 different kinds of mustard on a credit line that’s exponentially the size of one’s net worth or the ability to purchase any bullshit SPAC on the market.

I mean, WeWork, a company that was somehow too stupid to even IPO during ZIRP, managed to make it public and lose 99% of its value.

it’s been clear for a very long time that public market compliance has only gotten more onerous over time, such that the phrase “private markets are the new public markets” became ubiquitous post–2008, and it’s probably what led to the massive decline in publicly traded companies until everyone who bought and held SPACs lost all their money. Note that none of these compliance dodges have been closed, but rather monetary policy effectively killed the demand for bullshit speculation.

The problem with the SEC’s ignorance on SPACs is that it’s a direct contradiction to the enforcement route it’s taken on crypto, as I highlighted my analysis in the arbitrary treatment of the spot bitcoin ETF situation:

The SEC’s idea of “protecting investors from themselves”, as one would interpret all this hullabaloo about spot prices, is the kind of pithy intention that one could immediately invalidate with any number of practical examples, like the whole targeting and subsequent disappearance of Juul while any number of off-brand flavored vapes continue to exist.

The obsession with bringing cases against unregistered securities is similarly quixotic. As I noted,

Reading between the lines (and all my other blog posts) and other caselaw, we get a clear picture that the SEC just doesn’t like crypto anymore. Totally due to chance. Totally not due to any events that might have happened.

If you look at all the enforcement actions I’ve written about, these projects have largely blown up, rugged, or turned illiquid long before any of these actions were filed. Crypto was legitimate until FTX blew up in everyone’s face and Charlie Brown scrambled to attempt another kick of the ball by attempting to rectify a situation that the market had already settled.

Which brings us to Gary’s purview of private markets. Not content with creating a market that has entirely over-incentivized passive investment, the SEC is now focused on messing with private funds and market structure, with pretty much the entire industry united in backlash. You couldn’t get five of the heads of these private institutions to agree on a place to have a business dinner — it’s shocking that the front is this aligned from the industry. Look, there are two very clear issues with private funds: one is the unfettered, nearly limitless access to leverage, as Bill Hwang showed us, and the second is the “volatility laundering” that Cliff Asness repeatedly harps on. The SEC addresses none of this. Instead, it wants to change fund disclosures, pricing, term transparency, and more meaningless paperwork, thereby “evening out” the absurd spread between the compliance burden of a private and public fund. To even get access to these private market funds you have to be an UHNW investor or a mass of capital such as a pension fund. What exactly does increased disclosure requirements or “swing pricing” do for anyone, other than reduce the negotiating position of the private funds and fucking with their business?

A bipartisan group of 38 lawmakers has urged SEC Chairman Gary Gensler to withdraw the agency's proposal that would require open-end funds to use swing pricing…

In a Feb. 14 news release, ICI president and CEO Eric Pan said: "The (SEC) presents scant evidence of a real problem to solve. ICI estimates that daily dilution for U.S. mutual funds is on average far too small — typically just hundredths or tenths of a basis point per day — to incentivize shareholders to redeem heavily, contrary to what the commission assumes."

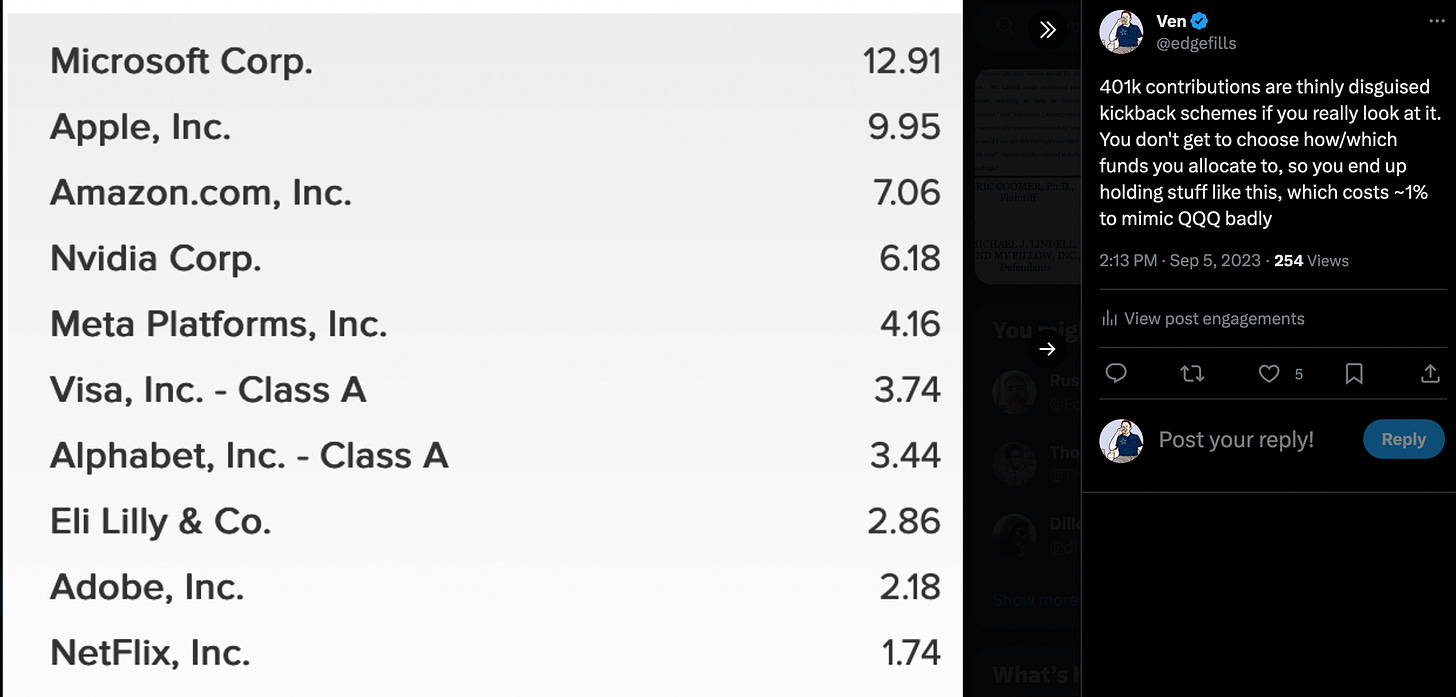

Mr. Pan also said the proposal would disproportionately impact retirement savers, as he noted 61% of 401(k) plan assets are held in mutual funds.

This kind of “arbitrary and capricious” thinking is present in pretty much every angle of the industry the SEC is looking to regulate, and addresses none of the very obvious issues I pointed out prior. Increased quarterly disclosures don’t matter if the mark-to-market is complete nonsense anyway. Finally, let’s revisit the PFOF nonsense. Joe Jackass buying some shares of a random stock is not going to impact the market due to the fact that he’s protected from smashing through the book like a crypto flash crash. The issue with retail execution is not the fact that it’s executed through Citadel, but rather that Citadel is never the one getting hit when things are actually volatile. This is a scaling issue, not a trading issue.

You can tell how “honest” the market depth is based off of the bid-ask spread, the depth of orders that look non-algo supplied (because when a price gaps, it’s not the market makers who are getting hit on the way down - they are the ones pulling the liquidity and trying to match depth on each side), and how quickly the book adjusts to the next price.

This isn’t a 1500-page-proposal issue — it’s a one firm issue. Inherently there’s a problem when one company houses a 60 billion AUM hedge fund and controls 80% of the flow. What the hell are we even doing here?

Making money in markets is already tremendously hard, which is why everyone is already essentially just punting and going along with AAPL, MSFT, and other big stocks. Maybe look at the fact that 401k mandatory contributions are forced kickback schemes.

Increased regulation and compliance only serve to entrench the biggest players because they have the cash flow to comply and the scaled margins to bear the burden. If you want to make markets more fair, take away the loopholes that can only be blasted through by billion dollar battering rams, not by making life harder for everyone.