Lately, I haven’t been getting much sleep (as my round-the-clock X posting would imply) — not because markets are in a drawdown, but because I recently came into possession of an abandoned dog. No, I don’t mean a Dog of the Dow — which doesn’t exist anymore, the DOW is just another NVDA ETF at this point — but an actual Doberman who got ditched in a park.

I was only supposed to keep him for a couple of days, and I didn’t think it would be a big deal — I’ve grown up around dogs my entire life, I can handle working breeds and what not — but apparently, none of the people who found the dog realized that he was essentially blind, making this a much more challenging endeavor than I thought. For one, these dogs don’t exactly sleep at night, as they’re guard dogs, but it also means that the regular model I had for training a dog didn’t exactly work.

An often-repeated aphorism of mine is that we design tech in the way we perceive our own mind to work. Random Access Memory, for example, is the logical conclusion of realizing that we can’t possibly memorize everything and hold it in our working memory all at once. Extending this to AI systems,

It’s shockingly intuitive — why we can mimic AI systems in our own brain is precisely because whenever these AI systems are built, it's to incorporate how we interpret things currently to the best of our ability at the launch-point. Thus, generative text is an attempted version of coding, say, my own stream of consciousness ranting and single data point extrapolation ad infinitum. (Though I don’t need prompting, just the occasional redirect and hard stop.) Computer vision just attempts to generalize and harmonize the relationship between approximate and precise viewing and using compute to approximate the intuitive process as closely as possible (as AI problems scale with compute, not efficiency.) Even deep learning neural networks are based off of early-brain development “sponge brain” — after all, you learned your first language from scratch by immersing in it, didn’t you?

we can see that “training” differs not whether it’s an algorithm or a dog. “Reinforcement learning” is essentially mathematical operant conditioning, is it not? Consider the Labrador, if you will. Dogs have a very rudimentary neural network at their core — highly responsive to positive reinforcement (treats) with rapid gradient descent (they index heavily into what you reward them for). Instead of GPUs, you have evolutionary iteration: a Doberman and a Golden are not working with the same processing power here. The end goal is to supersede the fact that a dog’s vision, even when unimpaired, is not that great — the goal of training is to bypass the impulse of the dog to do what it thinks is right and reduce the cognitive load of consciously processing what it can perceive around it with its senses, and trust your commands, similar to how baseball players swing a bat:

Hitting a baseball is one of the hardest things to do in all of sports, and it’s no coincidence that their eyesight is notoriously better than the population’s:

The results of visual acuity testing were most surprising. Certainly, we felt that professional baseball players must have excellent visual acuity, but we were surprised to find that 81% of the players had acuities of 20/15 or better and about 2% had acuity of 20/9.2 (the best vision humanly possible is 20/8). The average visual acuity of professional baseball players is approximately 20/13…

Our final area of focus has been on contrast sensitivity. Due to the importance of this function to both visual acuity and visual function on the playing field (i.e. tracking a white ball against the stands or against a cloudy sky), we used three tests of contrast sensitivity. Our results indicate that baseball players have significantly better contrast sensitivity than the general population.

So how do we explain that obviously you cannot consciously think about how to hit a 98-mph-fastball? Well, here’s the key — not all pitches are fastballs. The initial velocity and spin trajectory must be instantly approximated to even be able to whiff at the proper time. Thus we see the symbiotic relationship between the muscle memory of the brain but the processing of the eye — it’s unlikely that the brain plays a single part in a baseball swing (and why when the brain does come into play, it messes things up — choking and the yips stem from the pure eye process being disrupted.)

Of course, Waymo cars work the same way.

The end goal of all of this training is to make the approximation in the agent as close to a conscious, concrete, 100% validated decision. This is why gobs of data are needed for a car to “drive itself” — we are imparting the context-dependent intuition our brains are amazing at

However, humans have uniquely strong skills rooted in our intuition that are definitely mathematical. It’s not an exaggeration to label the human brain as the greatest pattern recognition machine to ever exist. We can contextualize relative quantities at a glance without ever consciously processing them — it’s the difference between choosing a larger pizza slice and guessing how many jellybeans are in a jar to win a prize. This scales to complex three-dimensional physics as well, as anyone who has hit a nice approach shot onto a green or made contact on a curveball would know. The overarching point is that humans have a ridiculous intuitive ability to approximate and extrapolate — isn’t that exactly what probability and statistics attempt to do?

The divergence between math and humans arises due to intent, methodology, and scalability. Applied probabilistic and statistical methods are just processes that can be optimally applied to certain problems. Which method you apply depends on factors such as the level of precision desired, availability, amount, and cleanliness of data, and how fast you want the result. Humans apply this type of thinking contextually. Beyond specialized activities, this usually means that these capabilities are only used when relevant to the individual. Humans are also creatures of evolution — these capacities were developed many millennia before the advent of computing. Here lies the crux of the confusion: human thinking was never meant to scale with the amount of data available. Rather, human intuition was honed on balancing accuracy relative to the available information and the speed with which the estimate needed to be made. Human ability is unparalleled when an approximation needs to be made on very little data, which is why casino games trap so many people. Humans simply cannot process the “long run” without putting it in the context of themselves without training the instinct out, which is why you can find endless amounts of people convinced that they’ve “solved” roulette that hawk “their strategies”.

so that, while a car may never know what a “red light” is, it can govern itself and act properly. Of course, I’d never let a stoplight tell me how to live my life, so you can bet in an empty intersection late at night I’m going to make a context-dependent decision.

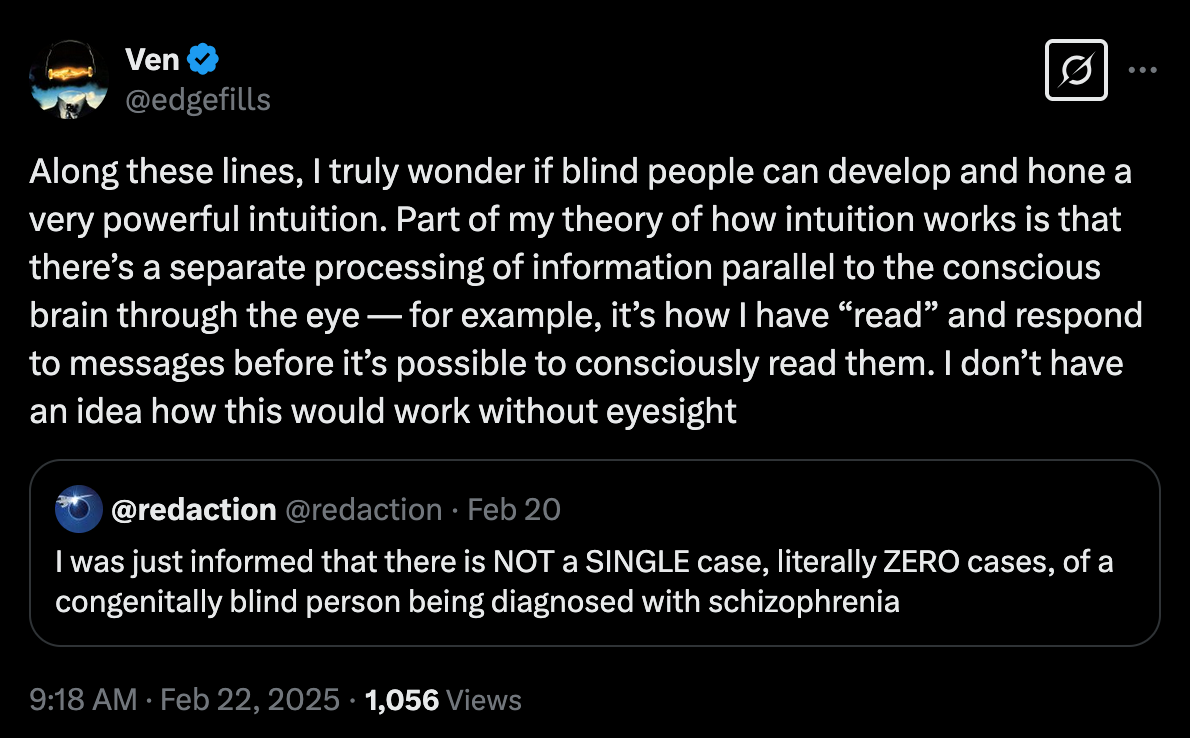

It’s interesting how this works, based on how processing power is segmented. A dog’s non-visionary senses are so strong that their intuition works best by bypassing vision, while for humans, I think it’s the complete opposite.

Part of my skepticism is that, as a result of the human world being so honed towards eyesight-oriented intuition, we’re losing the plot with computer vision. Enter the Doberman.

It was surprising to me that, when my friends handed him off to me after a couple days of a high-energy working breed terrorizing Coach purses and Cloud couches, that nobody realized the dog was blind. When I first walked him, his sniffing was on the tier of a working bloodhound stalking a trail, and that was just to get him to walk down the road. Usually, dogs only do that when they’re about to pee (or mount). After an evening of cavorting around, I sat down and thought — then bought a ball to take home and toss his way, which careened off his blank face with zero response. Now he’s scared of balls. The dog’s freaking blind!

This reorients the calculus with how you have to train these things. Sharp noises, scents, motion, reorient the algorithm better because the vision pathway simply isn’t there. His “gradient descent” was on a different pathway — an intense mapping process, not unlike how Tesla’s became the best car to drive in California. High-velocity objects with little traceable smells — cars, busses — drove the guy nuts until he felt the “threat” had passed, having to rely on the “whoosh” passing by to realize that it wasn’t coming for him. Apart from my dog growing up that was scared of the moon, I have never seen a dog more scared anything weirder than a rush of wind.

Within a couple days, I figured out exactly how to maneuver the guy around efficiently. High pitched, sharp noises — whistling — worked better than trying to find “a name”, dropping the leash and inducing motion gave him a “guidance” as to the proper vector to follow, and a few treats never hurt. Luckily, blind dogs love when you just pick the up and give them the solution every so often — unluckily, Doberman’s are fucking heavy, and lugging a 70 pound dead weight everywhere is a deadlift routine most are probably not used to.

In a sense, I think this past week outlined my AI skepticism from the genAI approach perfectly.

I have a bit of a joke that I’m a naturally occurring generative AI. For those of you who have read my around-the-clock, randomly disbursed X ramblings, sat with me over a drink, or had the misfortune of being in a group message with me, you certainly know what I’m talking about — that harebrained tendency to rapidly fill up a space with stream of consciousness and connecting topics by seemingly throwing darts..

I wasn’t joking when I wrote this — I can so fluidly meld topics together that I outright tell people to write “reprompt” when they want me to stop talking. My close friends have full license to cut me off when I get in a deep conversation flow as well.

I firmly believe an LLM structure is permanently limited by the fact that it will never “get” the context window. I remember every bit of reading and writing I’ve ever done — it’s just a question of when the reference becomes topical and whether I can find the source to cite it. Even the 8-bit dog brain understands the context window — I am the person who gave the dog treats and oriented it, so I have a heavy weight in its internal neural network. Is there any amount of training and GPUS that can ever overcome that gap?

Unfortunately, as much as I’d like to keep running tests with the Good Boy, a Doberman is not built to live with a person who travels nonstop on last minute notice and lives in a storage locker otherwise, as described by “Up in the Air”:

Kirn wrote the book in rural Montana during a snowbound winter on a ranch while thinking about airports, airplanes and about a particular conversation he had with another passenger in a first-class cabin. That passenger stated that he used to have an apartment in Atlanta but never used it. He got a storage locker instead, since he stayed in hotels and was on the road 300 days a year.

(Weirdly, he has me blocked on X for pointing out a stupid take of his about pawn shops.)

Google Malt Liquidity, idk.

An interesting thing happened when I was taking him in to the shelter to get processed/fixed:

As I’m walking in to the shelter, a pitbull breaks his leash and charges at my boy, flying and going straight for the jugular. Rips off his harness, thank god, to avoid a bloodbath. Six shelter employees come out and we end up breaking up a dogfight, but this dude didn’t back down — it’s a Doberman — and he eventually ends up bodying the dog back. A pitbull at that. Not gonna lie, I kinda get where Michael Vick was coming from — seeing evolutionary beasts just cut loose, even for 40 seconds, was a sight to see indeed. Here’s to you, dog I couldn’t name — maybe I refer to him in whistles and clicks, like that tribe in The Gods Must Be Crazy — and hopefully you find a worthy home.

Trouble drifting off to sleep? Maybe reading this will help,

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4139328

Very kind of you to be so patient with this dog.