Introduction

The concept of a futures contract is very straight-forward. Imagine that you’re a farmer plotting crop yields — naturally, you’re focused on the current season’s harvest, but obviously you know your lay of the land and have some expectancy of future yields. However, you are uncertain about price movement in the future, and are worried about price fluctuations (a.k.a. volatility, which is just an estimate of future uncertainty.) To hedge off risk, then, you might pre-sell some of that expected yield — you lock in a price conditioned on delivering a certain amount of your crop and take a sigh of relief as you reduce the burden of the unknown.

Electronically tradable futures contracts exist for more products than you could possibly imagine nowadays, including lean hogs, cocoa, corn, coffee (my personal favorite), Bitcoin, the S&P 500, and much more. Some of these technically have a deliverable as outlined in the scenario prior, while others are cash-settled. Most of the time, this deliverable is a technical formality (but we’ll get to this later.) However, there’s one particular commodity that’s banned from trading on futures markets entirely: onions. Hereafter, I will examine the peculiar history of why the onion is the Product-That-Must-Not-Be-Traded and assess what this circumstance implies about the entire construct of the future and its contracts as it was originally envisioned.

What Came First, the Future or the Crop?

Certainly, speculation and its byproduct, forecasting, have existed since the dawn of the conscious mind. The formal concept of a futures contract took shape in 1730, where feudal lords in Osaka, Japan, set up a system of “tickets” through merchants to sell rice to be collected as tax from future harvests in advance. Note that risk does not get erased — rather, it transfers. While the volatility in the lords’ expected income was blunted, the concept of delivery risk began to materialize. What exactly happens if you can’t deliver what you have already sold? In this case, almost certainly, the failure-to-deliver risk was just absorbed by the farmers and the underlings in the feudal structure without compensation. But in a more equal power structure, that future delivery date creates a pressure that amps up the risk as the date approaches. In effect, the future transfers the risk of spot (read: current) price fluctuations to a function of how close the time to expiry is and where the price fluctuations come. This, of course, is extremely nonlinear and creates a tricky environment to price risk, but as long as everything gets delivered properly, nothing can really go wrong.

Moving forward to the 1850s, an official exchange opened as the Board of Trade in Chicago, with the issuance of the first dated corn deliverable contract in 1851. Trading naturally aggregated around the centralized location as it created a more expedient way to match parties interested in transacting than time-intensive, individual negotiation. Furthermore, a neutral third party could bear witness to validate the transaction beyond verbal guarantees.

The birth of the standardized contract came a bit later in 1865. While the contracts that had been written prior could be traded to other parties, they weren’t standardized — these were forward contracts as they were negotiated directly between the two transacting parties with customized terms. Forwards became a subset of financial products called over-the-counter products that indicated a level of nonstandard terms and direct relations between counterparties. But in 1865, the modern form of the futures contract began trading — each issued future represented a specific amount of a specific quality of a specific commodity to be delivered on a specific date (known as an expiry or settlement date.) This concept still persists today: a Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Lean Hogs LN future, conceived in 1966, specifically tracks the price of 40,000 pounds of Lean Hogs, allowing any random person with sufficient data access to get an idea of the price movement of pork. Each futures contract issued will have a certain code that denominates the specific monthly expiry: the LNK24 future, for example, tracks the price of the deliverable that trades until May 14, 2024, and settles (nowadays, financially) on May 16, 2024. But let’s jump back to 1865 for now.

A key innovation that drove the creation of centralized exchanges and standardized contracts was the concept of liquidity, evidenced by the fact that the buying and selling of futures contracts wasn’t solely limited to farmers and consumers intending to take delivery. Anyone who had sufficient capital could trade futures contracts precisely because there was no guarantee that there would be a balance of bids and asks, or even an idea of what the spread was between the two. Traders provided the necessary function of playing an intermediary to allow producers and consumers to transact when convenient rather than firing orders blindly into a wide market. As anyone who observed the stock market in 2021 would have noticed, people will trade frequently for all sorts of reasons. In Larry Harris’s seminal textbook Trading and Exchanges, he outlines 3 archetypes of traders, described as follows:

Profit-motivated traders trade only because they rationally expect to profit from their trades. Speculators and dealers are profit-motivated traders. Utilitarian traders trade because they expect to obtain some benefit from trading besides trading profits. Investors, borrowers, asset exchangers, hedgers, and gamblers are utilitarian traders. Futile traders believe they are profit-motivated traders. . . They have no advantages that would allow them to be profitable traders . . . Utilitarian traders and futile traders lose on average to profit-motivated traders because trading is a zero-sum game.

Harris further categorizes traders as informed and uninformed. And, certainly, upon the invention of the standardized future, the most enthusiastic, active traders took the form of uninformed gamblers, treating the futures contract as another product in the vein of cards and horse racing. The main appeal of the futures contract was leverage and the seemingly straightforward real-world tethering: though the future might have bushels of corn as its underlying, obviously it would constrain liquidity to require traders to pony up the full cash amount to match the underlying, which would defeat the purpose of standardization.

Furthermore, what exactly was a future deliverable? There’s certainly a level of abstraction here, inherent to the concept of money itself. From a Baudrillardian angle, constructing a representation of an underlying that hasn’t been created or harvested yet invokes a concept which forms the root of “postmodern markets”:

First, you have the core business. It creates a product that is valued by society. Next, the abstraction of money comes in. This allows liquidity creation — if I sell socks, what am I going to do with unlimited socks? After currency comes the cap stack. We “value” the business to allow ourselves to offload risk on others. There’s no real way to properly value this risk: “fundamentals and valuations” exist as marketing, as every banker knows you price the deal at what you have to to get it done.

Futures were conceived to exist somewhere between the second and the third stage. It certainly represents actual farming capacity whose harvest can be sold for currency. But the forecasted delivery fluctuates as time decays to settlement — the spot will obviously reflect some sensitivity of the future price, but it’s not a linear or normally distributed calculation. Cash in hand is worth more than a yet-to-be-produced bushel, in a sense, so the price of the contract theoretically has to account for the net-present-value versus the net-future-value. Of course, a theoretical price is only worth what you can get a filled order at, so incentivizing liquidity provision requires margin lending and leverage in some manner that accounts for the cost of borrowing and the ability (or lack thereof) to pay any losses as well.

Bidder is Better

Naturally, this depth of thought was far beyond anyone’s consideration at the time. While the price of the underlying commodities organically had a tether to weather patterns, sudden inclement events, pest infestations, and more, the contracts traded because, well, people traded them, and speculation, informed or not, is highly addicting1. Futures trading enabled a kind of validation of the fortune teller: if the price moved in your favor, you made money, whether or not your thesis played out. The old Homer Simpson quote comes to mind:

This year I invested in pumpkins. They’ve been going up the whole month of October! And I’ve got a feeling they’re going to peak right around January. And BANG! That’s when I’ll cash in.

While Homer is a bit too on the nose in that clip, having money to figuratively burn was definitely the name of the game — as volatility and trading volume picked up, the hedging activities fell by the wayside, and though trading is a zero-sum game, when new players flock to the market like moths to a lightbulb, it creates the opportunity to accumulate wealth very quickly, regardless of what the underlying is or why it moved. This pushes us past stage 3: the valuation of what is changing hands is untethered from the deliverable for the time being, creating stage 4, the postmodern market state:

trading activity is totally abstracted away from any sort of reality whatsoever and collectively trades in a manner that resembles a toy model . . . market rather than as a reflection of reality: a pure simulacrum

Barring some turn of real-world events where price snaps back to reality (perhaps due to gravity) the price action moves purely on bid and ask, supply and demand, and who gets margin called (and, consequently, liquidated) first. The informed trader suddenly had another pathway to profit: beyond knowing the underlying, if one had advanced knowledge of how the liquidity might be impacted or which way the trading volume would move, they could set up a position to capture or drive a move, incentivizing market actors to update their idea of where the price should go. All trading is a function of information asymmetry, which directly implies that to profit off proprietary information, the market must realize it at some point2. In the nascent, limited-rules regime surrounding the first futures contracts, cornering the market became a viable strategy for enterprising, deeper-pocketed traders to attempt.

Cornering is an attempt to directly impact the price of a commodity by engineering a supply constraint in the deliverable and outstanding futures contracts in conjunction with the exponentially increasing rate of time decay as it lurches towards the settlement date. A corner is a fundamental trade based on a simple principle: each time a futures contract is bought (which contains the rights to the delivery at settlement), there must be someone who sold it to them (who is then on the hook for delivering the underlying). The total amount of contracts outstanding — the open interest — thus represents the maximum amount of the underlying that must be delivered on the settlement date.

Of course, open interest is not static — the point of the future is to insulate against price movement along the timeline to expiry, not just at the settlement date. If a seller’s forecast changed, they could always buy an equivalent number of contracts that they sold to close out any obligation they would have at settlement thereby “flattening” their position. Anyone who sold the rights to a delivery was “net short”, and anyone who owned the rights to a delivery was “net long”. Cornering consequently depended on both the ability to accumulate a critical supply of the delivery rights and the underlying commodity (and maintain its quality in storage — no small task) to pressure net short traders to either flatten their position or secure enough supply to meet their delivery requirements. A properly timed corner would result in a bidding war in both the contracts and the physical supply that rapidly escalated the price at which net shorts would have to pay the cornering party to flatten their exposure as time to settlement dwindled away.

One of the first major market corners came in 1888, when Benjamin “Old Hutch” Hutchinson bought up a critical mass of wheat futures. After a frost in fall killed off some of the wheat harvest, the price rose, and Old Hutch purchased “1 million bushels in a single trade.” At expiry, shorts had no choice but to pay off Old Hutch to close their obligations, making him a rich man and a source of frustration.

Of course, a successful corner created animosity and discontent due to the multiplicative losses suffered by those who couldn’t flatten in time, but this was in no way easy to pull off. If a trader tried to corner the market and other participants caught on before enough supply could be accumulated, they could potentially act in an adverse manner by refusing to sell to the cornering trader, coordinating activity between themselves, flattening exposure quickly, and more. While this could temporarily push the spot up, a corner critically relied on the feedback loop between the respective bids for contracts and the underlying supply. If any adverse event happened, the cornering trader could end up with a bunch of a commodity that wasn’t worth all that much compared to what they spent and borrowed to accumulate it. In 1891, when Old Hutch tried to corner the corn market, this is precisely what happened — he couldn’t accumulate enough supply, the contracts lost value, and he gave back a chunk of his prior gains.

Thus cornering remained an accepted market practice — after all, it did provide bid-side liquidity and was a strategy only available to the deepest pockets and the biggest risk-takers. Given that trading was pretty much a side hobby for rich men and regularly devolved into a battle of egos (which still happens to this day3) traders were willing to put up with the squeezes and busts as long as the game kept going and debts were settled.

Pickled Liquidity

While trading was heavily scrutinized after the Great Depression, significant regulatory actions mostly focused on curbing speculative mania in the stock market with the passing of the Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934, which created the Securities and Exchange Commission as a regulatory body to enforce the statutes. Of course, commodities were not securities as defined in the Acts, instead falling under the direct authority of the Federal government to regulate interstate commerce through the Commodity Exchange Act of 1936. Commodities regulation mostly focused on mandating the trading of futures in certain venues, giving exchanges the ability to set some sort of position limits and order type restrictions, and codifying the ability to punish dishonest or fraudulent behavior. Although the trading of certain futures was halted at times, part of the reason that commodities escaped a severe clampdown is that the futures were still tied to perishable deliverables, farmers still relied on them for hedging against price fluctuations, trading on margin was necessary to preserve liquidity, and seasonality tempered constant speculation — once the egg season was over, for example, trading in egg futures ceased. (Meanwhile, margin trading of stocks was heavily curtailed in the 1930s thanks to the Federal Reserve4.)

Post-World War II, onion futures were created by the CME to boost exchange revenue through driving volumes into a product that was less seasonal and could be stored for delivery year-round, and by the 1950s, it was one of the most heavily-traded contracts. While cornering shenanigans were still fair game, the tales of gamesmanship that went around began to attract actual negative attention. The traders themselves knew who was profiting from their losses, much like playing a weekly deep-stack poker game, and were content with the prisoner’s dilemma breaking any attempts at coordinated corners, but the CME had thinner depth of market than the Board of Trade, leaving it more susceptible to cornering. Furthermore, onion farmers had taken to the product’s intended utility, logically planting more as the spot rose, which occasionally led to supply gluts. Making matters worse, the price of onions was quite volatile in 1950, having dropped from $5.05 to 44 cents in just seven months, which led to many complaints from unhappy growers and allegations of illegal market manipulation. Consequently, in July 1955, Congress added onions to the list of commodities that the Commodity Exchange Authority could regulate. All the regulators needed was a reason to crack down.

Unbeknownst to the broader market, in the fall of 1955, an onion farmer named Vincent Kosuga and a man named Sam Siegel accumulated enough onions and onion futures to control 98% of all available onions in Chicago. As the spot rose, Kosuga and Siegel went to growers to cut a deal: as long as the growers would purchase some of the onion inventory, they would maintain their inventory, so the price wasn’t impacted. Else, they would dump their supply and crater the market. However, as farmers that weren’t part of the deal grew onions to sell at the stagnant price, Kosuga and Siegel flipped short and dumped their inventory into the market, profiting off both the price drop and the sale of the inventory. By March 1956, the end of onion season, the price had been pushed so far down such that the bags holding the onions were more valuable than the onions themselves, and the two men made millions in profit. Of course, many farmers were bankrupted by their entire supply being made worthless, and the regulators immediately stepped in. The farmers wanted the entire futures market killed, claiming it had been taken over by gamblers, while Kosuga, of course, protested that he was just profiting through legitimate market activities. The narrative was squarely in favor of the farmers, with an editorial published in 1957 stating that “Supply and demand no longer make the market. Now, it is done by gamblers…” Eventually, in August 1958, the Onion Futures Act was passed, and an onion future hasn’t traded since.

Curvature

Curiously, emotional rationale notwithstanding, nothing about the argument to specifically ban onions made sense. Cornering is a fundamental trade specifically centered around supply and demand — the entire incident was very much part of the structural design and a known risk of the futures concept. Think back to why onion trading volume took off in the first place — it wasn’t immediately perishable. Onions did not have the same “natural expiry” as eggs or butter did. Inadvertently, the CME had created a future in a fairly thin underlying where the spot could be significantly manipulated along the timeline to expiry, rather than the natural convergence that would induce predictable volatility at the end of the contract’s lifespan. Kosuga clearly had some inkling of this, though his actions were probably coincidental — as their supply of onions started to rot while they built a short position and began dumping into the market, Kosuga had the idea of shipping the rotting inventory out of the city to get them polished and sent back in, which implied to other traders that even more supply was about to hit the market, depressing the price further. Indeed, the wide price movements in onions could very well have been a collective miscalculation on how variably distributed sales of the supply were.

If you look at a Coffee (KC) future today, you’ll see quotes for not only the front (read: nearest) month expiry, but also for every standard issue (for this future, March, May, July, September, and December contracts exist for each year) so long as there’s open interest. This creates a curve, as not all months are created equal. If Homer Simpson purchased his pumpkins in September, the price of an October future would naturally account for the heightened seasonal demand compared to the December future. Traders nowadays are sophisticated enough to account for the interplay between spot and the rest of the term structure and cash versus physical settlement.

Is the Present Future the Future of the Past?

Nowadays, futures contracts are mostly cash-settled, reflecting the informal gentleman’s agreement in the pit days to flatten at settlement by paying for contracts rather than acquiring supply (barring a corner.) This also reflects the mass proliferation of futures trading in non-commodities, such as the S&P 500 future (ES), which tracks the stock basket and is the most heavily traded future in the market, or the VIX future (VX), which tracks a volatility index. Even when a future is physically settled (gold, coffee), a vast majority of traders flatten their positions before expiry and can “roll-over” their position by purchasing the next month’s contract, as there’s robust liquidity present in most products thanks to professional market-makers5 and electronic markets6.

Instantaneous order fills, robust liquidity, massive amounts of traders across the globe of every archetype and net worth, readily available real-time pricing7, and ~20 hours/6 days of the market being open a week have made futures trading a primarily stage 3 and 4 activity. It’s not even clear what exactly these cash-settled futures represent — apart from the tax advantaged treatment and the efficient leverage incentives to trade ES, what is an index future? The S&P 500 index is calculated off a basket of stocks, but it’s not actually traded. Instead, there are Exchange Traded Funds that actually hold the shares in that basket that make up the index. Thus, while the cash-settled future is synthetic (meaning that there’s no way directly utilize the future to create price impact on the underlying), the front month ES future moves in lockstep with the S&P ETFs in what’s perhaps the most well-known, competitive arbitrage trade of all time. Nothing moves in isolation,

similar to Newton’s Third Law — for every movement in a financial product, there is a product tied to it that will adjust accordingly (though not “equal and opposite” — there are far too many products built on top of products with non-linear relations for anything in finance to be this simplistic.)

Of course, even with this degree of interconnectivity, sometimes the price movement does reflect a real-world happening, whether it’s unexpected news, inclement weather, economic data release, and more. The Federal Reserve moving interest rates definitely factors into every sector on the planet. But a vast majority of intraday movement is trading volume that reflects no discernible reason whatsoever given the complexity and scale of modern finance, but rather implies a sort of passive drift as microscopic fluctuations in stocks are arbitraged to other stocks in the same basket that are arbitraged to other stocks in a different basket that are arbitraged to a synthetic future. Is there any illusion of, say, Starbucks’s daily coffee sales implying something about the next day’s price action?

Examining Bitcoin futures, there’s no trace of reality whatsoever. While regulators treat Bitcoin as a commodity8, ostensibly its price action is entirely devoid of explanation beyond pure bid-ask and supply/demand mechanics. Add on the fact that Bitcoin futures are synthetic and that an Exchange-Traded Product (ETP) holds a cluster of these futures and issues shares that purportedly give exposure to the synthetic. What exactly is an ETP that tracks a synthetic future that tracks a Bitcoin, and why should they track each other but for arbitrageurs deeming it so? It’s a pure simulacrum.

Back to the Future

Even in the simulacrum, reality has a way of popping up. (Hilariously, at the time of writing, the front month Crude Oil (CL) future is trading around 85 a barrel.) Each physically settled future has a standardized final settlement delivery procedure, and though this is largely a technicality, CL is one of the rare products where contract holders sometimes take delivery, with each contract representing 1000 barrels. Crude oil is also, well, toxic — taking delivery is not trivial, so accepting delivery requires timely notice of where the oil should go. Crude is an extremely volatile commodity and is regularly impacted by global events and production shifts from the biggest companies and OPEC. Entire governments get involved in trading to maintain a reserve. As a result, CL is the hottest commodity and has a large presence of utilitarian traders — big oil companies might collar their future deliveries to make expected profits more predictable, or governments might take delivery at seemingly low prices to accumulate reserves. Of course, there’s plenty of trading in-between, from 1 lot warriors to random 9-figure hedge funds seeking a thrill. Usually, the open interest is a non-issue when it comes to delivery — it’s simply far too deep a market to corner. How could you possibly corner the globe’s most critical resource?

Remember how Kosuga drove the onion price low enough such that the bag was worth more than the onions that came with it? Technically, this would imply that the onions were effectively negatively priced — nobody wanted to store a bunch of rotting onions, so anyone offloading supply was paying the difference between the bag and the onions to get rid of them. Presumably, avoiding the smell was worth it.

In March 2020, pandemic uncertainty had amped up volatility in markets to an absurd degree, and when the world reactively shut down seemingly overnight, trading truly moved to stage 1 for the first time since 2008 — every trade solely considered what was even going to exist moving forward. By April, at least some people had realized that the world wasn’t ending, but reality was still in effect — what were we supposed to do with the oil? It’s actually Econ 101: when demand drops off a cliff, so does the equilibrium price. Note that a single barrel of crude is a little more noxious than the permeating smell of a rotten onion:

“Could a barrel of crude really kill me?" I asked a petrochemical engineer captive to my persistent, doubtlessly annoying questions. It absolutely can, he said. Hydrogen sulfide gas—H2S, for short—has a terrible propensity to evaporate from crude, knock out your olfactory capabilities, and slowly suffocate you to death.

As the calendar crept closer to the May CL expiry, the world was collectively coming to a shocking realization: demand had nosedived, but oil production hadn’t stopped (for obvious reasons — you can’t just stop and restart a drilling operation.) All the unused supply had to go somewhere, but where? Every tanker was full — hell, every barrel was full, creating a quandary for a potential buyer, as they had to bring their own to take delivery — and nobody knew what was going to happen. If demand didn’t pick up, the most probable scenario was also the nightmare scenario, where both the buyer and the seller were trapped — if there’s nowhere to store the oil, how does someone take delivery? If there’s nobody to deliver the oil to, where does it get stored? On April 20, 2020, the unthinkable happened — the May expiry CL contracted closed at -$37.63/bbl. In a sort of inverse corner, everyone was playing hot potato with contracts to try and flatten their position at any price possible — the lack of bid on the contracts fueled the panic of figuring out what to do with 1000 barrels of oil (and ponying up the full cost for those barrels — everyone was trading on margin!), creating the doom loop that caused CL to bottom-tick at -$40.32/bbl9.

The negative oil incident was beyond the 4 stages entirely. While the corner trade was created by design and firmly rooted in the idea of fundamental thinking, the “inverse corner” arose organically from a collective cranial convergence of cluelessness and turned the idea of the product as value created on its head in a manner totally different from the Bitcoin ETP and its detachment from any recognizable reality. How could an objectively valuable, useful product — refined oil — be negatively valued for any period of time and fit into any framework of value creation? For those brief hours, the markets traded as a pure simulation of reality itself.

The Complex Commodity

After a few fortunes were made and the world got going again, the collective shock went away, and negative oil became a great anecdote “that you just had to be there for.” But consider the onion: for 66 years an onion has not traded on any lit exchange. As it stands, the onion is completely imaginary in finance. The concept of market-provided liquidity to enable valuation and risk-transferal that swallowed the world cannot acknowledge the existence of the onion.

Immediately after the passage of the Onion Futures Act, the CME briefly attempted a legal challenge to save their trading volumes. The case is fairly bland — CME’s claim that their business was intrastate and therefore outside the purview of interstate commerce was obviously bunk — but some choice lines are worth reading. Here’s a couple selected excerpts from the House committee’s investigation:

In contrast to some other commodities where there is wide use of the futures market for hedging purposes by buyers of such commodities, there is relatively little buyer hedging in onion futures. . . In spite of the improvements in the trading environment which have been brought about as the result of CEA jurisdiction and by action of the Exchange itself, it seems clear that violent fluctuations can still take place on the futures market without any relationship to supply and demand factors and that these price fluctuations can and will have an effect on the cash onion market. . .

The implication that there exists some minimum threshold of hedging present for a market to be legitimate along with the blatant refusal to acknowledge that this was a trade that could only have been made utilizing supply and demand mechanics is pretty telling that, no matter the argument, the government was putting their foot down. Here’s another zinger:

Plaintiffs argue that trading in onion futures is prohibited; that trading in the futures of all other commodities is permitted; that an unreasonable discrimination is thereby effected; and that the result of such discrimination is that the onion industry is deprived of the economic benefits of futures trading. These arguments are not well taken. As was stated by Circuit Judge Hastings in his memorandum opinion on defendant's motion to strike:

'There was much testimony to the effect that onions, because of their perishable nature and because of the fact that they are a relatively small crop and require very little processing before sale, are not a proper commodity for trade on the futures market.'

Consequently, assuming arguendo that the legislation in question is discriminatory, the discrimination is not unreasonable. To the contrary, it arises from differences which have been found to exist between onions and other commodities.

It’s quite funny that the very trait of lower perishability that drove its popularity amongst traders became a point against it specifically when everyone was mad about the market. But the Judge did accidentally hit upon something quite prescient about financialization as a concept: differences were found to exist because he found the differences. This kind of recursion is precisely how liquidity in a product develops in the postmodern market: it trades because it trades. Bitcoin’s liquidity has value because people value that liquidity and gravitate to the product whether its existence makes sense or not. For markets to progress from fundamentally-driven to liquidity-driven, the onion had to die.

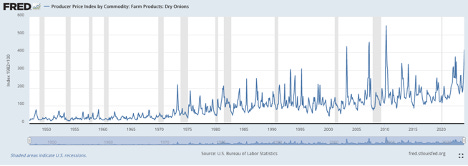

Of course, onions did not literally disappear. Onions are very much real and an essential ingredient to have around for quality cooking. Thanks to the erasure of the financial existence of onions, there is no good data to accurately assess whether the market served any purpose at all. The only chart I could find containing historical data was a graph of the PPI for dry onions,

and without a more granular view and the ability to account for market regime and inflation, all I can conclude is that anecdotally, I have never once heard of an onion shortage in the US that led to a point where onions were truly unavailable for purchase.

After all, it’s a crop that shares similarities and differences with other commodities — seasonality, inclement weather, supply chain issues, pests, and more all impacted the supply, but not the public market. The onion is the complex commodity: part of it is real, part of it is imaginary, and without it, the construct of reality would have never been extended to incorporate fiscal reality.

The Onion Futures Act is unlikely to ever go away, which means the onion will never get a futures ticker. Instead, I will denote the set of complex commodities with the symbol Ø. Perhaps in the future, the root of liquidity will trade again.10

Bibliography

While I didn’t underline where each sentence of the narratives came from, I did rely on a few books for some of the stories, linked below:

and, of course, a plug for the best textbook on trading ever written:

If you made it to the end, thanks for reading (and don’t forget the footnotes!)

This is well-documented in Ancient Indian texts, where compulsive gambling is consistently highlighted throughout epic tales. One of the most famous examples comes from the Mahabharata, where an otherwise virtuous king Yudhishthira gets hustled in a game of chance. In the game, Yudhishthira essentially martingales his “prized jewels ornaments from his treasury, his brocades, vestments, his mineral and precious metal savings; then his livestock, horses, his armies, slaves, servants and courtesans, then his lands, his capital, his cherished palace”, in what might be the earliest documented tilt of the variety you’d see from someone losing their shirt at craps in the average Strip casino. (He then proceeds to gamble away his four brothers and his wife, putting Dostoevsky’s gambler to shame.)

This might sound like I’m arguing in favor of the efficient market hypothesis (which is certainly beyond the scope of this post), but that’s the resultant state — the market is only efficient (strong or otherwise) if it reacts to and prices novel information. Of course, I find the actual hypothesis simplistic and mostly irrelevant for trading purposes, but it does directly lead to the realization that if you know when the trading volume will come and how the liquidity will be impacted, the principle of “minimizing hold time minimizes risk” is an immutable indicator of price edge during that hold time as long as movement is driven by active trading rather than passive tracking.

Like the battles for control of crop supplies, short squeezes in stocks have taken dramatic personal turns as well when priorities shift from making money to making the other side lose money. The class of hedge fund billionaires is similar in size and nature to a private college sorority beset by catty infighting. A favorite event of mine from recent history stems from Bill Ackman’s crusade against HLF, where he publicly took a large short position and claimed that the shares would plummet in value as the company was a multi-level marketing scheme. Ackman’s holier-than-thou reputation and an ill-mannered bike ride had rubbed his peers the wrong way over the past decade, so when Ackman went on CNBC to tout his position, a fellow hedge funder, Carl Icahn, dialed in to the show to refute Ackman’s claims, and the conversation devolved into playground insults traded on live TV, leading Icahn to take a massive long position to corner the supply of shares and make Ackman capitulate. Sensing blood, and out of pure spite, a couple more of their peers joined in to add to the pressure, and eventually Ackman had to flatten and eat the loss.

Though there are many decades of research on the causes of the Great Depression, certainly the major underlying cause was a complete freeze in the credit market — too much had been extended, too many entities across too many sectors were illiquid and/or underwater, and there wasn’t a strong enough central authority to provide emergency liquidity across the board. Of course, mania, panics, and crashes are closely related, and phenomena like bank runs and runaway inflation are a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts. A suddenly viral belief that a bank might not be solvent leads to people withdrawing cash out of a fractional-reserve lender thereby rendering them insolvent. Speculative mania is easy to blame for crashes, but lender profligacy and the untethering of money to productivity is a deeper philosophical issue.

Ah, yes, the much-maligned High Frequency Trading Firm rears its head here. In a basic sense, the role of a market maker is agnostic — all they do is facilitate transactions between buyer and seller when there isn’t a seamless match in price and quantity available. Every trade filled has to have an opposite end, and if I’m trying to sell my position and there’s no bid, there’s no guarantee of sufficient liquidity on the other side showing up. All the market maker does is constantly offer both sides so that I can sell to them and go about my day, and when someone else comes along, they can offload their inventory. Theoretically, they’d hedge their direct price exposure, but practically, they make a lot more through more esoteric trading methods. After all, market makers see the flow better than anyone else — they’re the informed trader. But they’re not coming for your 10 shares of GME, and the competition between firms and the fluidity of the technology means that the spreads are tight and available... unless the market turns volatile.

In fact, none other than Bernie Madoff was responsible for the proliferation of electronic market-making and the development of NASDAQ. Part of what was so vexing about the entire scandal is that objectively Madoff Securities was innovative and very good at what they did, which is what made the Markopolus report so shocking — there was no way his investment returns were legitimate, so the only possible explanations were that Madoff was frontrunning his own market-making business, or he was running a Ponzi scheme.

An iconic anecdote of mine takes place 35,000 feet above the ocean on a plane to Singapore, where I had to flatten out a fairly sizable ES futures position that I had idiotically placed prior to takeoff using an IRC quote bot.

Essentially because the price is purely a function of its liquidity — it does not fit any traditional category of products that trade, but just sort of gets a pass due to its massive market cap: “It’s not really clear what the common enterprise is behind Bitcoin, why it even goes up beyond people with unknowable expectations bidding it up, or whose primary efforts would cause price appreciation…”

After the second week of April, my phone did not stop ringing for 6 days straight. Ludicrously rare financial anomalies make me a very popular guy, I suppose. The only subject of conversation was whether to buy and how we could find storage. Everyone was collectively flying by the seat of their pants (or three sheets to the wind.) Shortly after the whole incident, rumors spread that 9 lads had figured out how to trade it and made $660mm on the price action. In a true echoing of the Kosuga “negative onion” end result, there was much clamor amongst traders and investors (and brokerages!) who had lost their shirts, and regulators vowed to look into potential manipulation. Nothing ever came of it though, other than this write-up of one of the greatest trades ever.

There was one modification to the Onion Futures Act that I forgot to mention. For whatever reason, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, whose purpose was purportedly to revamp financial regulation, modified the Onion Futures Act to prohibit the trading of contracts pertaining to “motion picture box office receipts (or any index, measure, value, or data related to such receipts)”. Of course, this language was placed before “or onions”, they really had to rub that one in. There’s no need to examine this ban — given how “Hollywood accounting” works, how can you create a future on revenue that won’t ever exist? There’s nothing complex here, it’s purely imaginary.