Edge is Everywhere

Some of my more daytrading-oriented readers may wonder why I spend so much time reading and discussing insider trading cases. Of course, I enjoy reading law, so it doesn’t feel like a waste of time, but it provides another angle of insight into a core philosophy of mine when I’m building trading systems. No matter the time frame or the nonlinearity of the edge you are trying to capture, you want your trade to predate the flows in the direction you profit in, whether this is spread-collecting on a microscopic time frame or preempting sector-rotations, portfolio rebalancing, tax-loss harvesting, and more. Predicting and trading ahead of flows is the most reliable way to buoy your returns — indeed, if one could reliably predict when the tape gets hit, it would be very hard to lose any money no matter the market conditions (cough cough). I am particularly interested in how the SEC make their cases on suspicious flow, because it gives me insight into other methods to try and detect informed flows. I have commented before on the general idiocy of the average insider trader:

Most notably, insider trading convictions rely on the irregularity of the reason of the trade, not necessarily the outcome itself — it’s possible to lose money while insider trading! That being said, if someone’s buying a metric ton of short term OTM call options, they probably know something that other people don’t. Of course, the golden rule is don’t insider trade, but you’d think that when people do, they’d at least disguise their flow.

What is constantly highlighted in SEC complaints is that they have access to extremely granular time&sale data. And while there are obvious patterns looking backwards, there are some signs on less liquid stocks that informed traders — not necessarily insider traders — with information asymmetry might be tipping their hand in real time. A simple example is outsized OI on, say, the call side and a certain strike relative to the put side on a very illiquid spread/stock. Note that stuff like block trades or put/call ratios aren’t indicators themselves — block trades especially are more on-tape “agreements” between parties to ensure liquidity at a price to prevent consuming too much book depth — but it is flow worth paying attention to. Every anomaly in accumulation across books and time frames and strikes is worth looking at — after all, these aren’t trades you have to predict, but ones that have actually transacted. (This is obviously the core usage of volume profiles, supports, and resistances, which, while not so straightforward to trade, reliably indicate certain pockets of available liquidity.)

The deeper realization that this led me to is that any sophisticated institutional trader who understands how to reduce their market impact in size and disguise their accumulation over time could pretty easily get away with building up a position on black or grey edge provided that there’s no obvious paper trail or whistle-blowing. Indeed, I’m pretty sure a fair chunk of historical hedge fund outperformance that wasn’t pure quant/execution edge involved some inside baseball — insider trading wasn’t really cracked down on until Raj Rajaratnam’s prosecution post-2008, where, curiously,

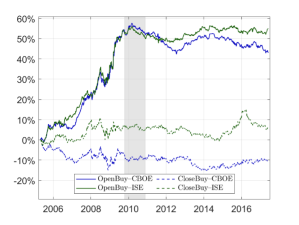

Before Rajaratnam’s arrest in October 2009, the put-call ratio strongly predicted stock returns. In portfolio sorts within the universe of S&P 500 stocks, the portfolio decile with the highest put-call ratio on a given day underperformed the bottom decile by 0.24 percent over the following week, or 12.1 percent per year. Moreover, the put-call ratio was more profitable than any other known stock anomaly when applied to S&P 500 stocks. Strikingly, the return predictability of the put-call ratio abruptly disappeared shortly after Rajaratnam’s arrest and remained absent for the rest of the sample period.

The figure below shows that the prediction ability disappeared almost immediately after the arrest.

Since then, while insider trading prosecutions have ramped up heavily, the SEC has shied away from taking on the absolute biggest names after the overreach in the prosecution of Diamondback Capital and the absolute saga that was the prosecution of SAC Capital and Steve Cohen, and more cases resemble this idiot trading on a merger they were working on for a few hundred k tops.

While the thesis of an insider trade is obviously illegal, the execution of the trade involves the same considerations of any other trading strategy — how does one maximize their return while minimizing the market impact and ensuring the ability to exit cleanly without tipping their hand (because this would obviously lead to being arrested, but also because when someone knows how you are trading, they can frontrun you) or over-leveraging (to prevent being liquidated before the thesis has played out)? As such, I got excited when I saw this paper titled “Using ETFs to conceal insider trading” — I have always monitored ETF compositions and inflows/outflows to some extent, but there are currently 2843 ETFs that trade, many with overlapping construction and prospectuses. This provides ample opportunity to disguise flow (both legit and illicit), so let’s take a look:

Our evidence suggests that some traders in possession of material non-public information about upcoming M&A announcements trade in ETFs that contain the target stock, rather than trading the underlying company shares, thereby concealing their insider trading.

The paper focuses on “shadow trading”, which revolves around not trading the underlying (or any derivatives) that the MNPI (material nonpublic information) is directly relevant to, but rather tangentially related stocks, which could be a competitor (as seen in SEC v. Panuwat), or in this paper, sector ETFs.

In some cases, ETFs are more liquid than their underlying components. In the case of potential small-cap M&A targets, it’s intuitive that a sector ETF with a certain % exposure to each stock could have deeper liquidity than in the underlying — while AAPL is certainly the most liquid stock in the market, it is inarguable that the exposure SPY gives to stock #392 in the index is much more liquid than #392 itself. The inherent problem I see is that you’d have to sort of rely on the merger implying a positive correlation between related equities on the news, rather than one target dampening the others. But even if the rest of the sector is uncorrelated to the merger, while your exposure to the merger is diluted through the ETF, it still should provide an actual pop as long as the acquisition target is sufficiently weighted.

Using a 13-year sample period (2009 to 2021) of all US companies and ETFs, we find evidence of widespread shadow trading in ETFs prior to price-sensitive news. Using a percentile test, we observe statistically significant increases in ETF volume in the five-day period prior to M&A news in 3-6% of same-industry ETFs on average. These ETFs, which are the most likely to be traded by insiders if shadow

trading does occur, have significantly higher levels of abnormal trading than various randomized control samples of other ETFs and other trading days. We eliminate M&A events that are preceded by rumors to ensure that the analysis is not picking up general information leakage.

Alright, the logic starts to break down a bit here for me. First, I think share volume is a lot less indicative than outsized options volume — while you could argue that ETFs are reliably more liquid than their small-cap underlying holdings, I definitely don’t agree that their options are reliably more liquid. ETF options have liquidity profiles that are all over the place — personally, I think monthlies on the underlying are generally more liquid, as that is what major holders of the equities themselves would probably use to hedge. Furthermore, I hardly think you’d need to resort to shadow trading an ETF to get off size in the underlying in a delta one fashion — the goal is to efficiently deploy capital to maximize return on the edge, while buying shares of an ETF is essentially the exact opposite strategy. Second, the primary volume driver of ETFs is arbitrage between the underlying components to the ETF itself — they don’t seem to correlate the increased volume on these ETFs with inflow/outflow data or control for implied volatility of the sector in the periods observed, where higher vol would naturally correlate with higher volumes, regardless of “news” in one of the underlying equities.

But I think the most damning critique of this analysis is the fact that predicting an entire sector’s reaction to one merger is nigh-ridiculous and a waste of edge. I suppose that if an ETF is heavily composed of the acquisition target in question, it would be a good alternative to trade, but to drag an entire ETF, you’d probably need the stock in question to be weighted well past the teens (which many ETFs explicitly prevent through constant rebalancing) along with ensuring that the other holdings don’t tank in response or due to natural market beta if the broader market happens to be red. For example, AAPL is about ~12% of QQQ, and they are obviously highly correlated on a longer term time horizon, but does this help you reliably predict how all of QQQ will trade with it intraday? Dispersion across ETF components is constantly present even though the heaviest components generally drive the movement. Plus, you’d need a similar outsized reaction across the board to even capture more than a small percentage of the move in the underlying you’re trying to exploit. Any holding not “rising with the tide” will kill the idea’s return.

Through time, shadow trading has increased from 2009-2013 to 2014-2019 which corresponds with growing interest and liquidity in ETFs as they become a well-established investment vehicle. We find that shadow trading in ETFs amounts to at least $2.75 billion of trading over the last 13 years or $212 million per annum. Our evidence indicates that ETFs are not purely passive investment vehicles, but they also play a role in insider trading strategies.

Okay, this is where this gets to a stupid level of misunderstanding of trade construction entirely. I don’t feel like the researchers who wrote this paper even considered how you’d structure a trade through an ETF to maximize edge — their “99% confidence level” is regarding $212 million in “suspiciously outsized volume” a year? This entire paper’s statistical justification means nothing. (Also, classifying ETFs as “purely passive” is hilarious in and of itself.) IWM — one of the major small cap ETFs — trades about $4 billion a day.

Overall, it’s definitely an idea — I’m sure shenanigans with ETFs have been tried, especially after the rather insane relationship between GME and the funds that held it during the surge. But I think trying to statistically measure swathes of mergers and relate it to share volume on ETFs is pretty silly. Frankly, this is the problem with most academic finance papers I read — nobody ever seems to think about how their assumptions and numbers would work practically as if they live-traded it themselves, or how they would go about searching for it in actual indicative, informed tape prints. The more complex your trade is, the more assumptions you have to make, and the more your edge is blunted, whether it’s MNPI or not. I have harangued you readers in the past few posts about how hard it is to ascribe definitive reasons to happenings in a complex system, and this is no different. Take all statistical evidence of a phenomenon with a grain of salt — if you can’t figure out how it could practically be implemented on a singular trade basis, odds are it’s not actual insight.