A Little Dark Edge

Malt Liquidity 138

Note: this is a long one. Would recommend saving for a rainy, lazy afternoon

1. Seeing What’s to Come

What exactly is a “fair” market? The market as a concept is the ultimate distillation of the anti-egalitarian approach to fairness: an equilibrium price is not a reflection of some rigorous formula that quantifies value, but rather reflects an agreement between the transacting party that the price is fair enough to transact at. The market inherently rejects the concept of equality — without asymmetry present, whether in supply, capital, or information, it cannot exist, and its existence implies continuing asymmetry in realized and future outcomes. Instead, the market attempts to generate “fairness” through efficiency — in an ideal state, it aggregates various asymmetries to produce a liquid, accessible venue that reflects all available information. While the nature is rooted in zero-sum thinking — every transaction has a buyer and a seller, and necessarily a “true” market implies that fluctuations must benefit one party over the other — a “fair” market is one that does not irrationally threshold access to its liquidity or arbitrarily dictate how it can be used. Thus, a more efficient market — one that rapidly ingests and responds to novel asymmetries while minimizing disruptions in functionality — is a fairer market due to concept’s inherent transparency: the market only reflects what is collectively known.

Setting the Randian rambling aside, when designing the structure and rules of a formal stock market, a thorny issue arises when deciding how to weight spot (read: current) price efficiency and future price efficiency in consideration of forward volatility (uncertainty) and the potential profit that can be made as it realizes. Prioritizing spot efficiency embodies an administrative philosophy of market design and emphasizes compliance with strict disclosure requirements with the purpose of minimizing the impact of proprietary information on forward volatility. The intended result is to favor utility-oriented market participants that transact according to their need for liquidity rather than speculative purposes. Prioritizing future efficiency, on the other hand, embodies a laissez-faire philosophy of market design, where the profit incentive created by unrealized volatility encourages market participants to transact according to their proprietary information, thereby continuously aligning their real-time actions with the ideal of an efficiently operating market. Realized volatility becomes the mechanic that validates whether proprietary information is valuable and reflects how valuable it actually is. Through a minimalist regulatory approach, the intended result is to favor market participants that contribute to efficiency by allowing them to take positions that are rewarded by the reactions of others.

All trades are made with some amount of information asymmetry present. On an individual scale, one’s perspective that develops an intention to trade is totally internal until it is shared, either incompletely by the placing of an order or explicitly detailed to others. Generalized, this means that every market participant, large and small, trades off non-public information. Put simply, why would you rationally take risk without having an edge, real or illusory? Every trading and investing strategy summarizes a form of this asymmetry and the manner it’s intended to be used no matter the time horizon. An activist hedge fund accumulates shares in a company because only the employees know what their intended strategical implementation will do to the business and the potential market pricing of the value they plan to deliver. A market-making firm only trades when their traders and algorithms have superior information from interpreting order flow as to whether they can execute properly and safely collect the bid-ask spread (or when they are legally mandated to offer both sides in exchange for compensation.) Therefore, market efficiency critically relies on the diversity of intent and scale across market participants, where the advantage of one party is paid off by the cost of utility valued by another — it’s only a zero-sum game if both parties choose to play the game.

As a result, regulation of markets becomes a precipitous balancing act between the related, but not synonymous, concepts of “fairness” and efficiency. A zealous approach to emphasize information disclosure has many externalities and begets the question of whether a market can truly reflect all known information in real-time (where the never-ending discussion regarding the efficient market hypothesis rears its head, which is well beyond the scope of this paper) and whether this dissuades optimal capital allocation and reorientation of investment. However, a hands-off approach can lead to unwilling parties being sucked into rewarding the best players of the zero-sum game to an outsized degree, thereby incentivizing speculation instead of value creation and potentially cultivating increased unscrupulous conduct. Fairness is a collective, subjective feeling, and if too many people feel that the game is unfair, they’ll just take their ball and go home, rendering the market useless.

It stands to reason that formal rules explicitly cataloguing what types of information can and can’t be used to trade are impossible to construct, unnecessarily granular, and would veer uncomfortably close to enforcing thoughtcrime. But the image of fairness obviously requires some sort of acknowledgement that a certain strain of malicious behavior will be discouraged and labeled as improper. This is the intuition behind the concept of “insider trading” — a layman certainly can sense what information can’t be used to trade, but rigorously defining what information forms the basis of insider trading is shockingly hard. The United States decided that the optimal framework was to assess insider trading using a common law, case-by-case basis rather than statutorily defining it. By allowing parties to make their case directly to the courts, both regulators and future market participants could benefit from the highly specific analysis of each individual case that arose invoking statutory authority, enabling a degree of self-regulation and voluntary compliance.

While enforcement of insider trading has varied based on social mores and regulator priorities, the recent result in SEC v. Panuwat indicates a shocking divergence in mentality as to how the current regulators view the profit incentive attached to information edge and the problems that an increasingly passive market poses to the concept of market efficiency. This paper highlights why the proliferation of passive investment necessitates increased enablement of trading on information asymmetry to preserve accurate price discovery, and how the current regulatory pathway is flawed.

2. For What you Stand to Gain

First, we have to understand why information even has a proximate value. As stated earlier, the existence of a market is predicated on the existence of an asymmetry of some sort. We can highlight that this asymmetry must exist in a scaled economic state where shares of companies are publicly traded by looking at the relationship that arises during their operations. Put simply, one can think of a market state arising when counterparties (here, companies) cannot reach an agreement on how to value a transaction. This is conceptualized by Coase’s theorem, which states that in the absence of transaction costs, private parties can negotiate (in a process called “Coasean bargaining”) a trade agreement such that an efficient state can be reached between them that values each’s property accordingly. If a Coasean bargain is successful, the two parties have then reached an optimal coordinated state, which is called a Nash Equilibrium in game theory. Of course, the Coase theorem would “assume liquidity”, where liquidity is defined here as “the ease with which an asset can be bought or sold”. Assuming liquidity puts us in a theoretical state which doesn’t accurately represent how transactions would occur in reality. The bargaining process highlights some examples of transaction costs, but the most notable ones for the purposes of this discussion is the value of information — most notably private information (e.g., an internal estimate of volatility in shared future outlook, or valuation of the company’s intellectual property) and asymmetric information (e.g., information one party has that the other is not privy to.)

Let’s look at what can happen when private information is an impediment to an agreement. Suppose company A is looking to acquire company B for some strategical purpose. Both companies have shared all the information necessary to fairly calculate a purchase price, but valuation is not a formulaic calculation — my refrain describing deal flow goes “. . . every banker knows you price the deal at what you have to to get it done.” If a disagreement happens and it can’t be resolved, what happens? Well, of course, the acquisition does not go through. When this process happens between two publicly traded companies, we get a core trading strategy called “merger arbitrage” (though arbitrage is a bit of a misnomer, as it’s not risk-free) that arises out of this process, where a trader can try and capture the price discrepancies between spot and acquisition price. When A and B are publicly traded stocks, the private information, once utilized to make an offer, will make its way to the market and impact the share prices of each company. Suppose the news leaks that A offers to buy B at $36/share while it is currently trading at $24. This represents a pretty significant premium of 50% if I purchased shares on the news! However, two considerations come into play: first, the transaction has to be accepted by the shareholders and management of company B, and second, the transaction is subject to regulatory approval. The price impact of the private information on company B thus serves as a proxy of the likelihood that the transaction goes through: if there is a $12/share premium available for capture, the amount the stock moves up on the news represents the market’s pricing of the probability that the transaction will go through. For example, if B moves up to $34 on the news, this indicates an ~83% chance (10/12) that the merger goes through. Of course, A’s stock does not exist in a vacuum — the purchase price (assuming a cash transaction, as we’ll do for simplicity’s sake) comes out of A’s assets. As a result, A’s stock will usually drop1 on the announcement, as the future value of the acquisition will be determined by the utility company B provides, while the immediate cash paid goes to B’s shareholders as compensation. Since the premium is paid to the target company, naturally, its price movement is more predictable — advance knowledge of an offer being prepared, tendered or the announcement of a completed deal subject to a review creates a profit opportunity for a trader to acquire shares prior to the market reaction that would thereby assign a value to the private information, whether or not the deal ends up going through.

Asymmetrical information adds an extra layer, in that the information could be related to pretty much any potential cost that might impact a company itself or any of its related companies. In the scenario outlined above, it could be the knowledge that Company A is internally valuing company B as a potential acquisition target, but could be deepened to any proprietary financial data, business strategy, or other information that could impact Company A’s activities relative to other companies, and therefore impact its share price. Notably, asymmetric information doesn’t necessarily have to have a counterparty to arise — in the case of having earnings data ahead of time, if one had advanced knowledge that Company A’s business has been performing better than expected (whether through proprietary modeling, research, or knowledge of the financials themselves), creating derivative effects that could impact the market. This raises a philosophical conundrum: how much of the price movement, once the information is diffused to the public, is even attributable to the information directly? In the prior case, the offer price was a defined value to anchor movement around. But when there’s no direct causality of the movement, attributing the market’s reaction to the proprietary information is a thorny assumption to make.

Furthermore, nothing trades in a vacuum:

It’s useful to look at financial markets from a standpoint similar to Newton’s Third Law - for every movement in a financial product, there is a product tied to it that will adjust accordingly (though not “equal and opposite” - there are far too many products built on top of products with non-linear relations for anything in finance to be this simplistic.)

Company A obviously has competitors, some of whom may be publicly traded. Intuitively, one company’s outperformance in a given market would indicate that other companies are not faring as well, potentially creating some tradability. However, this kind of second-order impact is simplistic attribution — the current market is filled with “sector ETFs” that hold baskets of stocks in one part of the economy, such as airlines, biotech, oil, and more. These ETFs rebalance allocations based on the amount of inflows and outflows to the product, making a movement attributable to pure technical mechanics of keeping an ETF in line with its underlying composition. The stock market is a textbook complex system — the primary regulator concern should thus center around not overattributing movement and volume that coagulates around information as directly attributable to the information itself, especially during periods of elevated or blunted volatility. That being said, all information is not equal: in industry parlance, “black edge” refers to obviously illegal information that should be restricted from trading on, while “gray edge” refers to proprietary information that would naturally result from investing effort into discovering it2. Separating the lines between gray and black is where insider trading regulation comes in.

3. All Limits of Disguise

Insider trading regulation essentially began with the passage of the Securities Act of 1934 after the Great Depression, where there was a general consensus that some regulation of speculation in securities was necessary and gave power to the newly-created Securities and Exchange Commission to do so. Part of the Act’s focus in curtailing illicit trading activity centers around literal company insiders: large shareholders, directors, and other officers were required to disclose their holdings to the SEC and restricted when they could adjust their holdings and how they could profit from those transactions, though the disgorging of those profits was left up to private litigation, rendering it somewhat ineffective3. However, none of this legislation really prevented the colloquial idea of “insider trading” — purchasing securities on the basis of illicit information. This prompted the passage of SEC rule 10b-5 in 1942, which formalizes the concept of the insider created by possession of material non-public information (“MNPI”):

It shall be unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, by the use of any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce or of the mails or of any facility of any national securities exchange,

(a) To employ any device scheme, or artifice to defraud

(b) To make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading, or

(c) To engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person,

In connection with the purchase or sale of any security.

A key insight when 10b-5 was constructed is that, obviously, it was impossible to encompass all information that was “material” in precise legal language without running roughshod over the proper functioning of markets. Instead, the law envelops the use of the information to purchase securities as a variant of fraud. This lends itself very well to a caselaw approach — in disputed cases, a trader accused of utilizing insider information will have recourse, with the burden of proof lying with the SEC to show not only the materiality of the information, but also the connection to the purchase. Of course, one cannot reasonably expect a trader to be well-versed in the nuances of insider trading caselaw — a question arises regarding the level of knowledge of the source and type of information the trader must have in order to intentionally insider trade. This also implicitly broaches the subject of the source’s liability — if another person gives the trader a tip, are they responsible in some manner? As caselaw will show, this depends on the financial age.

4. Knowing What’s Nearby

The first major caselaw applying 10b-5 focused on what should happen to MNPI already in the possession of an individual in a 1961 case involving a stockbroker from Cady, Roberts & Co. The broker, upon gaining knowledge of a dividend cut in a company’s stock that he held for his customers, sold the shares prior to the news being communicated to the public. His trades were deemed to fall under 10b-5, thereby creating the “disclose or abstain” rule, which states that being in possession of MNPI requires one to either disclose it or abstain from trading on it. The disclose or abstain rule was the lens with which the courts first touched on materiality seven years later in SEC v. Texas Gulf Sulphur Co. (1968), where employees of the defendant mining company discovered an ore site and subsequently purchased shares and options in the company between November 1963 and April 1964. On April 16, 1964, a full press release detailing the discovery of the ore site was released, which further clarified and corrected an ambiguous press release on April 12, 1964. The court set a threshold of materiality of information when finding that 10b-5 applied to the employees’ trades, in that the duty to disclose or abstain only arises “in those situations which are essentially extraordinary in nature and which are reasonably certain to have a substantial effect on the market price of the security if disclosed.”

An interesting bit of context here is the length of the timespan the court took into consideration regarding the share price movement: it noted that when drilling began on November 8, 1963, the shares traded at 17 3/8, and documented fluctuations on key dates up until May 15, 1964, where the stock traded at 58 1/4. Intuitively, we can conclude three subjective concepts arise when considering materiality:

a) the rate of information exchange that sets the purview of what price movement is potentially relevant

b) when the information becomes potent enough to be material (in this case, when the ore site is discovered? When the mining begins to take place? When a sufficient amount of ore to impact the business has been extracted? etc.)

c) whether the amplitude and directionality of the move is implicative of the effect of the information (which will all become highly relevant in the advent of algorithmic trading and passive market structure.)

Neither of the cases prior particularly addressed the definition of an insider because it wasn’t really in dispute. Insider trading caselaw, after all, develops due to a general sense of unfairness, and the events described don’t broach the question of whether it was unfair to subject the traders to 10b-5 in the first place. This is perhaps due to the fact that ordinary people didn’t really trade stocks in the first place — while infamous speculators like Jesse Livermore existed in the early 1900s, the stock market was still majority institutional investors and professionals in the 1950s, and retail trading wouldn’t take off until the late 80s4. However, the Supreme Court did give further insight on 10b-5 in Chiarella v. United States (1980), where a man employed as a printer gained knowledge of a pending acquisition from handling the documents themselves and subsequently purchased shares in the target company. The Court stated that the printer had no duty to disclose or abstain under 10b-5 due to the fact that his access to MNPI was in no way that of an insider who had been entrusted with the information in confidence, but rather “a complete stranger who dealt with the sellers only through impersonal market transactions.” This reinforced the idea of 10b-5 as a type of “information fraud” — for conduct to be insider trading, the MNPI had to inherently create a duty to disclose or abstain that made the possessor an “insider”, which the Chiarella Court considered to be some type of fiduciary. Thus, the scope of the “insider” was clearly centered around the company possessing MNPI and the relationships that access hinged upon. (As to the actual trade the printer made, the SEC obviously saw it as unfairly benefiting people who happened to exist in the pathway of information transmission and passed Rule 14e-3 to restrict all trading related to MNPI about tender offers regardless of whether duty was present.)

Just 3 years later, the Supreme Court upheld the fiduciary standard from Chiarella in Dirks v. SEC (1983), where Dirks, a financial analyst, received a tip from an ex-officer of Equity Funding of America that alleged vast overinflation of the assets held by the parent corporation. After investigating and confirming the tip, Dirks shared his information with the Wall Street Journal, who declined to report his analysis, and multiple investment advisers who consequently sold their shares. Although Dirks was clearly not a fiduciary with regards to the MNPI, the officer who tipped him did have a duty to disclose or abstain present. The Court, while understanding that analysts contributed to the healthy functioning of markets by investigating tips and interpreting information, was nevertheless wary about insiders tipping MNPI and profiting indirectly — the duty to disclose was to the public, after all, or otherwise to abstain from trading. To preempt this, the Court constructed tipper-tippee liability, where the tipper, if found to benefit directly or indirectly from the disclosure of MNPI, would breach their duty to disclose or abstain, and the tippee, if aware of that breach, would be subject to that duty accordingly.

As access to the markets increased and the number of participants swelled, the SEC was given an additional tool to apply 10b-5 by way of the Supreme Court’s ruling in US v. O’Hagan (1997), which gave rise to the “misappropriation theory”, where a party who traded using MNPI could be found to have breached a duty owed to the party that entrusted them with MNPI rather than disclose or abstain duty, which was to the public. Subsequently, the SEC enacted Rule 10b5-1 to clarify that trading “on the basis of” MNPI encompassed all trades made while aware of MNPI, thereby removing a trader’s claim that they would have made the trade regardless of the MNPI, but allowed for pre-planned, binding sales (usually used by company insiders.)

The caselaw can be condensed to outline a framework where the courts determined that market fairness and efficiency roughly falls between as follows:

Materiality scales with market impact and reduction of variance in the outcome space of a trade. Information relating to tender offers are the defining example of guaranteed impact and maximal reduction of variance, so trading with this knowledge should be heavily discouraged.

Materiality has to maintain relevancy both with respect to the security traded and the timeframe during which the trades were made. Relevancy must be scrutinized more closely when claiming causality of derivative effects.

Company insiders and any contractor privy to MNPI are entrusted with it specifically for the company’s purposes. As a result, their trades should be limited and structured to stringently avoid the image of impropriety. Such parties using MNPI for personal gain through quid pro quo agreements must be forbidden.

Analysts and other investigative parties play a critical role in preventing cover-ups, identifying potential fraud, and ensuring the accuracy of forward disclosures. Profit potential is likely needed to incentivize this conduct. A clear understanding of MNPI being received as a fiduciary or with the expectation of confidentiality should be present to create a duty to disclose or abstain.

Misappropriation of MNPI by a party to trade or to otherwise gain personal benefit through quid pro quo agreements with another party to trade can violate a duty of confidentiality to the owner of the MNPI if that is how access was given. However, materiality should still be scrutinized, especially if the MNPI is not directly traceable to the security traded.

A framework, however, is useless if it cannot fit to dynamic market mechanics, technological progress, regime shifts, and changes in administration, which will be examined next.

5. If You Hide, it Doesn’t go Away

A critical assumption that underpins all trading on the basis of MNPI is that a company’s shares represent a set of values contained in the company it denotes an ownership stake in. These values include quantitative information, such as financial statements of past performance, real assets and intellectual property belonging to the company, qualitative information regarding the future outlook of the business and the overall environment, and the right to future cash earned. However, the share price is simply the equilibrium between the price levels and quantities that market participants are willing to bid and offer shares at. The assumption dictates that when the company’s set of values shifts, market participants interpret the new values in the context of the prior state share price as they become aware of the shift, and the price reaches a new consensus. Thus, a trade on MNPI requires a catalyst to capture profit — if the market never learns the information, it can’t move the share price accordingly. Intuitively this implies that the strongest catalysts center around acquisitions, where the buyer clearly anchors the value to a price and the terms of the offer. Reflexively, the strongest proof of materiality in an insider trading prosecution is when the information pertains to a takeover.

Though there was precedent-setting caselaw, as mentioned earlier, insider trading was rarely prosecuted prior to the 1980s, partially due to the market environment — volume was sparse and information took time to travel, rendering tough questions about materiality to overcome — but also due to the fact that the SEC didn’t have much of a way to punish insider trading, as it could only file civil cases forcing disgorgement of profits made or losses avoided, while criminal cases had to be referred to the Department of Justice and beared an elevated burden of proof.

However, Congress empowered the SEC throughout the 1980s by giving it the ability to prosecute criminal cases, reward whistleblowers, and require public companies to write insider trading policies. It was no coincidence that these increased powers coincided with a massive boom in the role financialization played in markets due to easing monetary policy and the innovation of novel financialization techniques that, amongst other things, turbocharged merger activity

The first major figure to go down for insider trading was Ivan Boesky, prosecuted by none other than then-U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani. Charged both civilly and criminally, Boesky disgorged well over $100 million and was sentenced to 3 years in jail. Similar cases sowed the seeds for an interesting dynamic where prosecuting greed was good, not only for market participants, but for the political prospects of the prosecuting attorney, given the unsympathetic nature of ultra-wealthy defendants and the venue of the cases naturally clustering around Manhattan.

Another trend that coincided with the SEC’s increase in powers was the electrification of market operations, pioneered by none other than Bernie Madoff. Independent of the infamous Ponzi scheme, Madoff’s brokerage was at the forefront of disseminating stock quotes through computers rather than phone calls, which increased the availability of price information and the frequency at which it was updated. During the 1980s, Madoff Securities became one of the largest electronic market makers and was the first major firm to implement payment-for-order-flow5, which drove a significant amount of retail (read: non-professional, smaller size) trading flow. From a trading purview, retail traders were generally regarded as less informed and placed trades that were less value-driven as a result. However, the massive increase in retail trading also meant that, from an insider trading purview, the “public” that the duty to disclose was behooved to was larger and more reliant on regulatory protections than institutional investors. Further complicating things was the concurrent rise of electronic trading beyond order execution, where primitive forms of arbitrage and technical trading were being implemented. How exactly would “material information” factor in a numbers-driven trade?

Truly, the emphasis placed on insider trading prosecutions was pretty much up to the SEC in the 1990s. The entire concept of MNPI revolved around creating a level playing field that didn’t prioritize parties with heightened access over others, but could retail ever be on a level playing field with deep-pocketed firms investing heavily in technology and employees to develop strategies? If enforcement chilled information seeking such that the market strayed too far away from representing value, what exactly did it represent? With so many varied intentions of market participants, could information even be causally attributed to market moves?

In any case, there wasn’t much done to resolve any of these questions in the decade after Black Monday. After Michael Milken pleaded guilty in 1990 to multiple securities violations (though nothing related to insider trading), merger activity was still plentiful but driven by cheap borrow cost rather than tricks using leverage, and stock demand was growing through mutual funds rather than individual company names. The market was in a massive bull run — what regulator would stick their nose in lest the music stops due to them? The pattern that created the SEC itself was beginning to emerge: speculative mania led to a bubble, the bubble would eventually pop and cause panic, the panic resulted in a crash, with the resultant finger-pointing resolved through lawsuits.

The 1990s introduced an added complexity in that technology had once again advanced through the development of the commercial internet, which enabled new heights in trading innovation and rate of information exchange. While the general public flipped Beanie Babies and internet stocks skyrocketed, a new breed of hedge funds had emerged, the most notable of which was Long Term Capital Management. These funds focused on the deepest markets on a global scale — forex, fixed income — to allocate as much as possible to juice returns. LTCM went further. Started in 1994 by John Meriwether (of Liar’s Poker fame) and chaired by economists Robert Merton and Myron Scholes (of Black-Scholes formula fame), LTCM plunged many multiples of its $5 billion assets-under-management into convergence trades and exotic derivatives to capture a perceived mathematically-modeled edge, reaching nearly $1.3 trillion in notional exposure by 1997. By the end of 1997, LTCM had returned over 80% after considerable performance fees to its shareholders. By the end of 1998, it had failed, and its positions were unwound.

The collapse of LTCM highlighted that, in the internet era, the assumption of price’s relation to value wasn’t fully valid. While simultaneous crises in Russian and various Asian financial instruments were the catalysts that blew up LTCM’s positions, trading was driven by heightened volatility that spiked far beyond what LTCM’s models accounted for. Real-time stock quotes throughout the trading day couldn’t feasibly be connected to the underlying business and its activities. A larger order could even move the price around if there weren’t enough sellers to absorb the order. At least on shorter time frames, it was becoming clear that market microstructure and price action was dissociated to some extent from the value assumption.

The subsequent implosion of the Dot-com bubble after the turn of the century reinforced the notion that the idea of the market as a mechanism to congregate information and rationally value it was naïve and flawed. Small investors felt particularly wronged by the apparent lack of substance of securities regulation, having been led astray by analysts issuing positive reports about stocks they “investigated” to supplant bid while the brokers they worked for allowed higher priority clients to offload their shares. Amidst all the chaos and self-interested behavior, it's almost certain that MNPI was being passed around and traded on throughout the decade. During widespread speculative frenzy, though, is monitoring MNPI beyond the obvious tender offer even worthwhile, given the effort of sourcing the data and proving a 10b-5 violation? The broader scope of insider trading law beyond tender offers doesn’t help level the playing field when the market isn’t primarily driven by information, and there simply isn’t enough news to ascribe a reason to each movement even on a weekly basis. Focusing on insider trading could even become counterproductive by further reducing the ability of material information to reprice the market and counterbalance pure speculative surges.

Prior to the 2008 Great Recession, insider trading prosecutions were rather muted as other blatant instances of corporate misconduct were prosecuted by Eliot Spitzer, another New York prosecutor that gained a reputation for being tough on white collar criminals (and, later, a more infamous reputation for another sort of criminal activity.) The notable exceptions were the insider trading charges levied against various Enron executives following the company’s iconic collapse, which included Chairman Ken Lay and CEO Jeffrey Skilling. While newsworthy, their trading was bog-standard company insider usage of MNPI and amounted to little more than an additional count given the litany of other charges Enron’s insiders faced.

After 2008, however, insider trading prosecutions kicked into high gear. Once again, another New York attorney was attempting to make a name for himself. This time, it was Preet Bharara, who was appointed as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York in 2009. While the Dot-com bust could be ascribed to widespread irrational exuberance, this time, the crosshairs were directly aimed at the financial sector and its speculative excesses. Stricter insider trading regulation wouldn’t have prevented anything, but the connotation of a successful prosecution would align with the vindictiveness present towards wealthy hedge funders and validate the feeling of righteous anger — they were cheating the whole time! Given the lack of significant cases after O’Hagan, perhaps funds had been operating under a false sense of security.

That all changed when Raj Rajaratnam, the billionaire CEO of a hedge fund named Galleon Group, was arrested by the FBI, and charged with insider trading in October 2009, shortly after Bharara’s appointment. Curiously, a trading pattern changed almost immediately after Rajaratnam’s arrest:

Before Rajaratnam’s arrest in October 2009, the put-call ratio strongly predicted stock returns. In portfolio sorts within the universe of S&P 500 stocks, the portfolio decile with the highest put-call ratio on a given day underperformed the bottom decile by 0.24 percent over the following week, or 12.1 percent per year. Moreover, the put-call ratio was more profitable than any other known stock anomaly when applied to S&P 500 stocks. Strikingly, the return predictability of the put-call ratio abruptly disappeared shortly after Rajaratnam’s arrest and remained absent for the rest of the sample period.

Note that by 2010, markets were very much in the “high frequency” realm where trades were executed at the millisecond level. Since there hadn’t been a major hedge fund insider trading case in recent history, nobody knew what evidence the government had — it stands to reason that trading on MNPI could have gone unnoticed as long as the trades didn’t obviously indicate prior knowledge of an acquisition. An indicator with predictive signal suddenly decaying overnight implied some wariness in the parties trading in that fashion, given that the government has access to robust time&sales data available for executed trades that get flagged. Later on, it was revealed that the FBI had a wiretap on Rajaratnam’s phone and caught him trading on knowledge of upcoming earnings reports. In May 2011, Rajaratnam was convicted on all 14 counts related to insider trading.

Bharara proceeded to secure 84 more insider trading convictions and guilty pleas across the hedge fund world before losing his 86th case, ironically against Rajaratnam’s younger brother, in July 2014. However, the bleeding didn’t stop — a pair of convictions was overturned on appeal on the basis of Dirks, which led to seven more being dropped by Bharara himself.

Bharara’s most ambitious prosecution was filed against Steve Cohen in 2013 after multiple successful prosecutions against employees of his hedge fund, S.A.C. Capital (the subject of Black Edge.) Bharara’s strategy of flipping lower ranked employees failed to incriminate Cohen — though one of Cohen’s traders, Mat Martoma, was convicted for profiting off of one of the largest insider trades ever made, there was simply no way to tie the MNPI used to any trade Cohen made himself. While S.A.C pleaded guilty and settled all insider trading related charges, Cohen escaped criminal charges entirely, bringing an end to Bharara’s enforcement campaign in 2016.

It’s hard to say that Bharara’s campaign definitively leveled the playing field beyond instilling some unqualifiable sense of deterrence and creating a lot of jobs in compliance. The market regime organically shifted dramatically away from the “hot tip” culture that allowed Bharara to run up his record after Rajaratnam’s arrest — markets had become less volatile, traded lower volumes, and shifted towards passive management, while algorithmic trading strategies essentially replaced valuation-based strategies, rendering the value of MNPI somewhat moot at the institutional level.

After Bharara, the sedentary market environment produced some rather amusing prosecutions, but nothing posed a particularly novel question regarding 10b-5 itself. Many prosecutions remained centered around unsophisticated traders buying short-term call options using advance knowledge of an acquisition due to the extreme predictability of reactions to the announcement and the ease of timing and accumulating exposure. Of course, this is similarly easy for the SEC to prosecute, as seen in the case of Bill Tsai, a first-year banking analyst who, within a year of graduating from New York University as the student president of Stern Business school, purchased call options on a stock whose merger he worked on. Within a year, Tsai was arrested, barred from the securities industry, forced to disgorge his profits, and sentenced to 90 days in a halfway house. Bharara’s prosecutions had the effect of transforming 10b-5’s reputation as a rule that ensured proper governance of company insider holdings and discouraged selfish behavior into one that would be used as punishment if the narrative demanded it and a sufficient number of a target’s peers could be pressured into cooperating. Given that there still wasn’t a clear understanding of what constituted insider trading, one wonders whether the punishments doled out were even effective, given that Cohen, once the terms of S.A.C.’s settlement preventing him from managing outside money expired, immediately raised $5 billion when his new hedge fund opened. One imagines Bharara’s subway ride home was something similar to Agent Denham’s after the events of The Wolf of Wall Street. Where was the vindication?

However, as 2020 rolled around, the market environment was about to undergo its most dramatic shift yet.

6. Picking Through the Cards

The effects of lockdowns on markets from February 2020 to March 2022 created the most actively traded, mass-participation regime imaginable. Due to people stuck inside with nothing to do while government checks rolled in, trading volume across every asset imaginable (and unfathomable) exploded, as did stock option volumes. In terms of relevant events to insider trading, however, only two things that happened during this time period need to be noted: first, that the share value assumption was now completely invalid, and second, that Gary Gensler became the new SEC chair in 2021.

The death of “value” as a concept in markets is highlighted in other posts on this site, but this passage in particular summarizes the post-2020 construction of markets:

“why do things trade?” The only correct answer is because other people are trading it. This is the root of “postmodern markets” as I call it, or “simulacra” as Baudrillard does:

First, you have the core business. It creates a product that is valued by society. Next, the abstraction of money comes in. This allows liquidity creation — if I sell socks, what am I going to do with unlimited socks? After currency comes the cap stack. We “value” the business to allow ourselves to offload risk on others. There’s no real way to properly value this risk: “fundamentals and valuations” exist as marketing, as every banker knows you price the deal at what you have to to get it done. Finally, we have the security as it’s traded now, where the activity is totally abstracted away from any sort of reality whatsoever and collectively trades in a manner that resembles a toy model . . . market rather than as a reflection of reality: a pure simulacrum.

This framing of markets severely limits the concept of “materiality” as causal market impact is notoriously hard to determine outside of price-anchored information. Concurrently, stocks that aren’t seeing active flow (flow unrelated to keeping passive products in line with their underlying weights) have never been less likely to move in isolation, as evidenced by the number of ETFs rising from 276 in 2003 to 8754 as of 2023. Meanwhile, the number of publicly traded stocks dropped from 8000 in 1996 to 3700 as of 2023. It’s eminently unclear as to what a market capitalization implies at all at this point: a cryptocurrency token depicting a “dogwifhat” holds a market capitalization of $2.7 billion, while Spirit Airlines, a company with over 12000 employees and $5 billion in revenue, has a market capitalization of $400 million. If there’s no coherent explanation as to what exactly a market cap consists of and a rational way to value it, how exactly does one calculate any damages attributable to insider trading? Consider the case of David Stone:

An Idaho man who hacked the Motley Fool site and made millions of dollars trading on its stock recommendations before they were made public was sentenced to more than two years in prison. . . Prosecutors said Stone used another person’s credentials to access Motley Fool’s internal systems in 2020, enabling him to see the popular personal finance site’s stock picks before they were released. Stone earned more than $4.8 million in profits trading on the information. The government said he also tipped off another person who traded on the information and made more than $3 million in profits. . . According to the SEC, the pair traded the stocks of dozens of companies recommended by the Motley Fool in 2020, including Amazon.com Inc., Coinbase Global Inc. and Peloton Interactive Inc.

For context, this is what AMZN and PTON did in 2020:

What possible causality does a Motley Fool recommendation have regarding the movement of two pandemic stocks that everyone piled into? Certainly, there is an illegal use of proprietary information present, but it’s totally illogical to apply the misappropriation theory to these trades. One logically concludes that, in the postmodern market state, only price-anchored or event-anchored MNPI should continue to be heavily restricted.

The SEC under Gensler, on the other hand, will do no such thing regarding insider trading, seeking to push novel interpretations of what constitutes a 10b-5 violation. In August 2021, the SEC charged Matthew Panuwat under a novel interpretation of 10b-5, claiming that after receiving MNPI regarding the status of a potential acquisition of Medivation, his employer, he violated his duty to abstain by purchasing call options in a similarly situated competitor named Incyte. On April 5, 2024, the jury returned a verdict finding Panuwat guilty. The core problem raised by this precedent is that the trade in question took place in 2016 under a totally different market environment. Undoubtedly, Panuwat, as a senior director, was an officer of Medivation and had a duty to abstain. But misappropriation of MNPI as a breach of duty requires some sort of fraud or deceit perpetrated on Medivation as a result of his trade. This raises the question of materiality — from the framework outlined earlier, as a derivative effect, relevancy to Incyte shares should be scrutinized closely. While Incyte shares rose 7.7% upon the public announcement of the acquisition, associating this kind of linear relationship — if A happens then B follows — from a single trade made 8 years ago and enshrining it under 10b-5 is an absurd conclusion to make when sector ETFs have proliferated in every imaginable nook of the market. Wouldn’t it be logical to allow highly skilled corporate employees to utilize their information and drive active flow to areas of the market they find mispriced?

Of course, the kicker is that all this analysis is moot anyway — Medivation had an insider trading policy that prohibited any trading in “the securities of another publicly traded company, including . . . competitors”, meaning that Panuwat violated his duty no matter the materiality of the MNPI relative to Incyte, since any trade placed would breach the conditions of his employment and access to MNPI. (Of course, whether this is too broad of a policy to be enforceable is another question, but it explicitly highlights competitors.) Accordingly, on appeal, hopefully the shadow theory can be put to rest.

7. Open Eyed, Burn the Page

The balance of fairness and efficiency that insider trading law attempts to maintain is rooted in the idea that share price movement over time reflects the shifting value of data and news specific to the company. That body of information is thus owned by the public, giving rise to the notion that knowing more than what is available is “nonpublic” information. If that nonpublic information has sufficient predictive power of how the value will shift once revealed, then it becomes “material”. When scaled, this creates a market where each stock has an intrinsic value that fluctuates as more information is disseminated and an extrinsic value that fluctuates relative to other stocks’ performance and the overall economic climate. Trading volume in such a market would recurringly spike around newly released information and dissipate after. In this market, any knowledge about an acquisition would be supremely material — there is nowhere else the price can move.

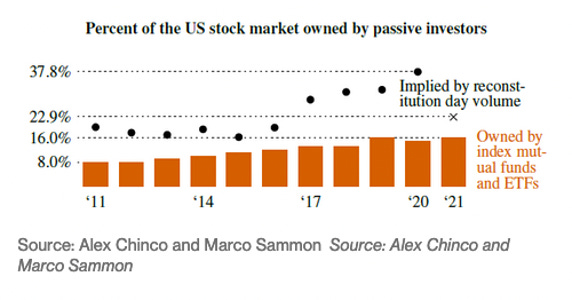

This, of course, is the ridiculous market design that results from prioritizing the ability to effectively apply insider trading law. Electronic quotes, round-the-clock trading, and fast execution dispelled the illusion that value is what drives share price over time. Are the daily sales of Starbucks locations reflected in the real-time share price? Is it even possible for that information to be collected, shared, and valued so quickly? Increased computing power allowed for robust computation and analysis of how each stock trades in relation to one another and the whole body of stocks. This creates the concept of the market as a relational complex, where little patterns between all the individual tickers exist to be captured. Once the patterns mature, the idea of diversified, collective ownership takes place, so the occasional material news doesn’t crater an otherwise healthy portfolio. As more stock ownership mimics this model, stock baskets are created to further cheapen the cost and streamline allocation. These baskets are theoretically redeemable for the net value of the underlying assets, so a mechanism that trades the patterns between each asset to each basket it sits in develops. As larger amounts of the market flow to the baskets, an increasing number of stocks lose volume in their underlying, solely drifting as a function of the baskets they attach to. The occasional material information drives some trading activity, but it’s quickly dampened by the historical patterns realized. This hypothetical passive market highlights the stark reality that a majority of movement in such markets is largely unattributable to the type of information governed by insider trading law, with the sole exception of tender offers.

The current market state is not that far off from the hypothetical described prior, with the exception that there’s still a significant amount of information edge due to speculative trading. As long as speculation continues, whatever the reason, the ability to predict volume and trade around it will create profit opportunity. None of this is MNPI — it’s too fast, too small, too order-specific. There is no way to level the playing field between a firm with cutting edge technology and high-skilled employee and the general public. However, this isn’t as bleak as it sounds. Diversity of strategy, size, and intent when trading is necessary for a market to be liquid and efficient, and those firms want nothing to do with the other side of most trades beyond collecting a spread.

The real concern is, if market participants go passive or leave for another asset class, what exactly drives price discovery in the underlying stocks? This indicates that even if a move is not attributable to a particular “material” reason, there is still capturable edge present if the underlying is actively traded. After sustained capturing of such edge, other traders will take notice and trade similarly, reinforcing the intent behind the trade and the patterns that arise from it. The way insider trading law becomes relevant again is by deprioritizing MNPI trading restrictions involving everything other than tender offers and everyone other than corporate insiders, and heightening the standard used to assess “materiality” of information, thereby increasing the value capturable and increasing the impact of information on individual ticker price movement. The optimal market finds balance between fairness and efficiency, and it certainly avoids passivity.

To be continued in the discussion of DFV/GME events shortly…

Though there are exceptions — a notorious example was when Amazon purchased Whole Foods, where, upon the deal announcement, Amazon’s stock rose by more than the value of the cash they were paying to acquire it.

Much of what I refer to that isn’t links comes from a few books. I’ll list them in footnotes, but feel free to ask me specifics. This one is from Black Edge by Sheelah Kolhatkar.

The Law and Finance of Corporate Insider Trading: Theory and Practice by Nasser Ershadi & Thomas Eyssell

Wall Street, a History by Charlie Geisst.

The still-used (and much iterated upon) practice of paying incentives to traders that direct volume through your brokerage. This would allow spread collection using that order flow rather than having no volume at all.